Part I

In 2013, an Israeli geneticist named Eran Elhaik published a bombshell article in the Genome Biology and Evolution Journal (published by Oxford University Press) that essentially sought to prove that the origin of Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewry lies in a group of warriors who were known as the Khazars. The Khazars were a warrior kingdom converted to Judaism in the eighth century and reigned over an empire stretching from the Chinese border to Kiev. Elhaik claimed to have innovated a new cutting-edge technology that compares the genetics of Ashkenazic Jews with sample DNA from modern-day populations who are supposedly genetically related to the ancient Khazars. Who were the Khazars? The Khazars were an ancient group of Turkic Mongol warriors who adopted the Jewish faith, although the exact circumstances—as well as numbers that actually converted—are shrouded in mystery. The medieval Spanish sage Rabbi Yehuda Halevi wrote a famous book called the “Kuzari” that purports to be a record of the debate between the king of the Khazars and the representatives of the Muslim, Christian and Jewish faiths. Eventually the king becomes convinced that Judaism is the true faith, and he and his family plus his advisers of the upper class convert to Judaism.

By the second half of the 10th century, the Russians would eventually and decisively defeat the Khazars in battle.

What does all of this have to do with Ashkenazim? There has always been somewhat of a mystery of how a population of Ashkenazim that numbered only 50,000 in the 15th century had exploded to over 8,000,0000 by the 20th century. Elhaik’s thesis engendered a firestorm of responses both pro and con. Professor Shaul Stamper of Hebrew University wrote an article titled “Are We All Khazars Now?” where he exposed the faulty methodology used by Elhaik. Crucially, there is not one population that we can point to today with certainty as being the descendants of the ancient Khazars. Most importantly, Stampfer shows that the demographic question is a non-starter; for instance, he shows how modern French Canadians and modern white South Africans have exploded in population from tiny founding groups. There were other faulty methods that were used in Elhaik’s analysis. The question regarding the origin of Eastern European Ashkenazic Jewry has been explored many times throughout modern Jewish history.

The general consensus has been that Eastern European Ashkenazic Jewry originated from Western Europe, particularly German-speaking lands. However, there were some outliers, like assimilated Hungarian Jewish writer Arthur Koestler, who published a book called “The Thirteenth Tribe” where he purported to prove that most Ashkenazic Jews were in fact descended from the ancient Khazars. Evidently Elhaik was not the first person to come up with this idea. The problem is that the numbers do not seem to add up, but as Professor Stampfer shows, the numbers can be fickle.

It seems clear that the so-called Khazar hypothesis has been decisively debunked; the coup de grace could be the words of the Rema who flourished in 16th-century Poland. It seems clear that by the 17th century, the bulk of Eastern European Ashkenazim would be situated in the territory of Poland, and indeed it is the Rema’s opinions that the Jews of these territories followed (in contradistinction to the Sephardim following Rabbi Yosef Caro and the Shulchan Aruch). As mentioned, the Rema in his introduction to his perush on Shulchan Aruch leaves no doubt as to the roots of Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewry:

ולא זה השולחן אשר ערך לפני ה’ ולא נתנו עדיין לבני אדם אשר במדינות אלו, אשר רובו מנהגיו במדינות אלו לא נהיגינן כוותיה – – – כי כבר אמרו ז”ל אין למדין מן הכללות, כ”ש מן הכלל שכלל הגאון הזה לעצמו לפסוק אחרי הרי”ף והרמב”ם במקום שרוב האחרונים חולקים עליהם ועי”ז נתפשטו בספריו הרבה דברים שאינן אליבא דהלכתא לפי דברי החכמים שמימיהם אנו שותים שהם הפוסקים המפורסמים בבני אשכנז וצרפת… אשר אנו מבני בניהם,

-דברי הרמ”א בהקדמתו להגהות השולחן-ערוך

Rema’s glosses supplement the law presented in the Shulchan Aruch with the conclusions derived from the views of the authorities of whom Caro did not take account, particularly those of Germany and France, “whose waters we drink and who are the eminent authorities of Ashkenazic Jewry and have always served as our eyes, and whose rulings have been followed from the earliest of times, namely, Ohr Zarua, the Mordechai, Asheri, Semag, Semak, and Haggahot Maimuniyot, all of whom built on the Tosafot and the halachic authorities of Germany and France, whose descendants we are.”

Ancient Pathways

Anyone who knows anything about (Hungarian) Jewish history has heard of the sheva kehillot, or as they are known in Yiddish and German, sieben gemeinden, literally seven communities. These communities are located in the Burgenland region, which is situated on the border of easternmost Austria and neighboring Hungary. They included the communities of Eisenstadt, Mattersburg/dorf, Kobersdorf, Deutschkreutz (Tzelem), Frauenkirchen, Kitsee and Lakenbach.

According to local lore, Jews have had a presence in this region since the eighth century, but this was never taken seriously by scholars. The first documented presence of Jews here begins in the 14th century. In 1670, King Leopold expelled the Jews from Austria. Many of the refugees settled in the Burgenland estates controlled by the princes of the Esterhazy family (the Burgenland region had managed to maintain a degree of sovereignty). They received a writ of protection and a charter of rights that helped make the communities flourish and attracted a steady stream of immigrants from all over looking for a better life.

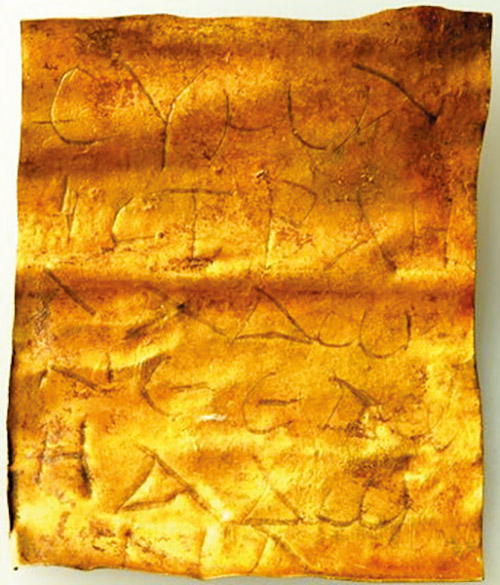

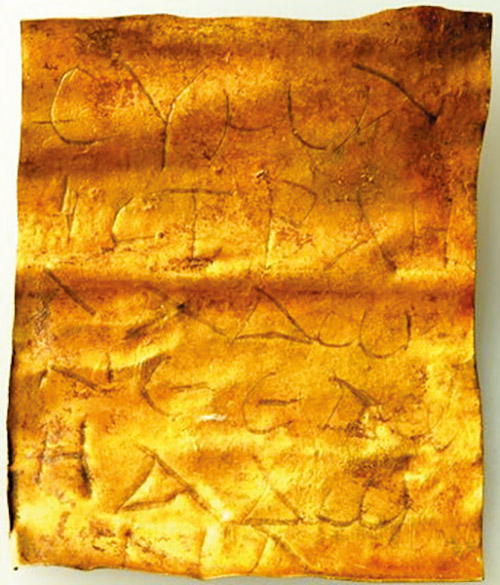

In 1986, Austrian archaeologists discovered a golden amulet from the third century among hundreds of ancient graves in the Austrian town of Halbturn. In 2006 the Institute of Prehistory and Early History of the University of Vienna announced that they have deciphered the inscription. The amulet reads: ΣΥΜΑ ΙΣΤΡΑΗΛ ΑΔΩNΕ ΕΛΩΗ ΑΔΩN Α, which plainly transliterated reads: “Suma Istrahl Adwne Elwh Adawt N A.” It is clearly a poor transliteration of the Shema prayer: Shema Yisrael, Hashem Elokeinu, Hashem Echad.

Just to give an idea where Halbturn is located, it lies about 35 miles from Deutschkreuz (literally, German Cross, which is why it was called Tzelem by the Jews) in the modern Burgenland region of Austria.

There was obviously some sort of Jewish community in Burgenland dating back to before the time of the Mishnah, which is pretty remarkable.

To be continued…

The author is available for scholar-in-residence and other speaking engagements and can be reached at yoelswe@gmail.com.