Tisha B’Av the world over is observed through fasting, expressions of mourning, the reading of Megillas Eicha, and the recitation of the Kinos. In our times, at least, communities and individuals have often supplemented these activities with additional experiences, hoping to create added meaning and relevancy to the commemorative day.

In the early ’90s I photographed the annual torch-lit procession on Tisha B’Av night at Camp Morasha in Lake Como, Pennsylvania; I attended day-long learning programs in Brooklyn and some of the other boroughs; I sat with others in air-conditioned synagogue halls and multi-purpose rooms watching Tisha B’Av films and interviews. But one Tisha B’Av afternoon in the late ’80s, a few years after I graduated college, I wandered around parts of Harlem and looked at structures that used to be synagogues.

My grandfather was born in Harlem in 1900. As a young child and then a young man, Harold Harris attended Congregation Ohab Zedek, north of where it is today. Its full name was First Hungarian Congregation Ohab Zedek, and Yossele Rosenblatt was the esteemed cantor. My grandfather would proudly volunteer that information in the 1920s and 1930s during countless job interviews, when asked what “church” he belonged to after his credentials had been readily confirmed. His response was always: “I belong to Congregation Ohab Zedek, Yossele Rosenblatt is the cantor…”

I heard this story numerous times, and my grandfather always ended it the same way: “I’m sorry Mr. Harris but we don’t hire Jews.”

Decades later, I would walk through Harlem on many shabbosim and yomim tovim— from my apartment in Washington Heights, to the Upper West Side—sometimes three miles, sometimes five, and sometimes doubling that with a return trip. I even organized a final Rosh Hashanna minyan at a shul on 157th Street. This was in the late ’80s, and was inspired by my Tisha B’Av afternoon walk to see the synagogues that once were. I wrote an eloquent message and papered the walls of Yeshiva University’s main campus with photocopied signs inviting students to be a part of the last synagogue in Harlem’s very last minyan. The synagogue was just outside the boundaries of Harlem, two blocks north of the Hamilton Heights-Washington Heights border. It also wasn’t the very last synagogue in Harlem—it was the southernmost of what’s referred to as Northern Manhattan.

Indeed, Harlem still has one active synagogue, which gets press attention for just that reason, and it is one I frequented on many occasions. The Old Broadway Synagogue, located a block east of the intersection of Broadway and 125th Street, is a reminder of the heyday of Jewish life there during the first two decades of the 1900s. Toward the latter part of this period, the Jewish population reached as high as 178,000. But as the Jewish migration away from Harlem began and quickly grew—relocating to the Bronx, Brooklyn, and the Upper West Side—the synagogues relocated too. Over the short span of nine years, the population dropped to only 5000 by 1930. For Jews, Harlem was over and the houses of worship were abandoned. As any Tisha B’Av afternoon walk similar to mine will reveal, many former synagogues are now churches, some are empty, and some, whose large buildings no longer exist, have been replaced with new structures.

Visiting the places where synagogues once stood, where Jewish communities once thrived, can be one way of internalizing the meaning of Tisha B’Av, especially if their exterior architecture and Hebrew inscriptions are still visible, and there is no Jewish life within. From the beginning, synagogues in all the generations have been mikdashei me’at, smaller versions of the Temples that once stood in Jerusalem. Tisha B’Av mourns the destruction of the Temples, and as the Talmud says it is “a day of crying for the generations” that laments other calamities and tribulations in Jewish history. The Temple functioned as a concrete sign of God’s presence, of His relationship with the Jewish people, and its destruction continues to suggest His absence, even as we have grown accustomed to the exile.

Today we are able to visit the courtyard of where the Temple, the grandest of all synagogues, once stood. Our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents, who lived prior to 1967, were not able to do that. In 1967, there was a euphoria that surrounded the unification of Jerusalem, the capture of the Temple Mount during the Six-Day war; Mordechai Gur’s declaration that “the Temple mount is in our hands”; the sounding of the shofar; the recitation of the blessing of Shehechianu. But today the actual site of the destroyed Temple is a place almost too alive to truly feel the destruction and abandonment.

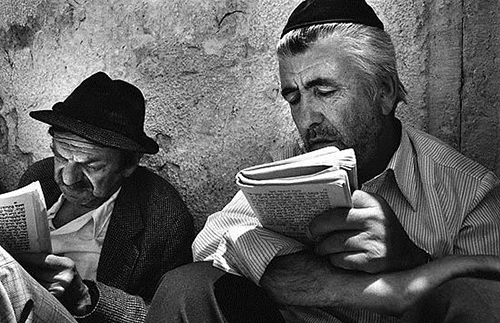

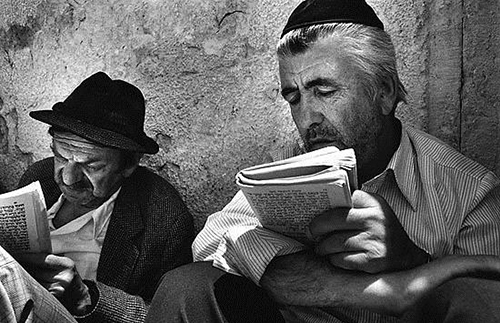

During the daytime it often bustles with people of all types, ringing with the sounds of prayer, conversation, and nearby traffic. It’s a destination now, and familiarity has softened its impact. In our times, the Kotel must be one of the most iconic of Jewish images, its looming presence, the strength and size of its stone, and even the knowledge that we are gazing at only a smaller section of the total expanse of the Western Wall.

I was more moved when I took a tour of the archeological excavations along the Southern Wall. The guide pointed out the stairs that led up to the Temple mount via Hulda’s Gate, noting the stairs were those used by the people of Israel who were oleh regel, during the three appointed holidays. For me, the stairs brought the past closer.

It was a sunny day, the sounds of the crowds and the noises of the buses and cars, though diminished, could still be heard in the distance. There was a time when tens of thousands, even more, came to Jerusalem to a functioning Holy Temple, a combination of the miraculous and, from ample descriptions, of the glorious. It was all so long ago, and some have the custom in the synagogue the night of Tisha B’Av to announce the number of years that have passed since the destruction of the Second Temple two millennia ago.

A few years ago on the Shabbos before Tisha B’Av, the rabbi in my shul gave a talk. He said he wished that the sorrowful day, on the following Thursday, would be somehow transformed into a holiday, a day of celebration. This Thursday? I thought… Five days from now? Really?

Judaism has an essential belief in waiting for the redemption. We believe it will come and we wait for it each day. The Rambam says this basic tenet means that each and every day we are hopeful that God will redeem the Jewish people, “at the appropriate time.” And no matter which generation will be redeemed, the entire nation, past and present, will benefit. We are all connected to the destiny of the Jewish people; each Jew is a point on the continuum of Jewish history.

Waiting for Messiah conveys a concept that just as Judaism is a dynamic religion, so too is our history. There is more in store for us as a people, for sure, and also for the world at large. Much remains unresolved. To believe in the imminent redemption is to feel a desire today for a closer relationship with God. Each day we feel the absence of His presence, and we are like children awaiting the return of a parent, who run to the window to peek out from time to time, who know something is missing, something is not complete.

That year, Thursday was mighty soon, and this year it’s the same. But what about the question that faithful Jews probably wonder about: “Will the Temple actually be rebuilt in my lifetime?” “In my lifetime,” provides a little more room for opportunity, but it still sounds not much different, and perhaps no less a fantasy than “this Thursday.” But still the promise: “Those who mourn for Jerusalem will merit to see it in its joy,” says the Talmud (Taanit 30B), basing its assurances on a phrase in the last chapter of Isaiah that encourages all lovers of Jerusalem and all who’ve mourned her to rejoice in her revival and her rebirth.

Within the sadness of the Tisha B’Av day coexists a future holiday, a time of rejoicing. Within the mourning and sorrow lives the promise of happiness and of joy. The abandonment feels real, but the trajectory more so.

Judah S. Harris is a photographer, filmmaker, speaker and writer. Judah’s photography has appeared in museum exhibits, on the Op-Ed Pages of the NY Times. To learn more about Judah S. Harris, visit www.judahsharris.com/visit.

By Judah S. Harris