“You’re going where??? ”

Over the course of seven days in February of this year I had the privilege of traveling together with my 19 year old daughter, Julia, and her Midreshet AMIT seminary classmates on an in-depth Jewish heritage journey across Poland, under the expert guidance of JRoots. This journey was similar to the one many yeshivas and seminaries have run in recent years.

During the months leading up to this trip, a simple, yet powerful question was frequently asked of me: Why? Why would you stop your busy life in New Jersey and spend a week plus to travel to Poland, a place steeped in a history of destruction and despair for our people? And why give them your business? What could a Jew possibly find in Poland in the year 2023?”

Aside from being a student of history and fascinated with travel to exotic (not sure Poland is “exotic”) places of the world, I gave this question considerable thought during the days and weeks leading up to the trip. But the answer crystallized in my mind only after spending the week in Poland and having the experiences that we did.

First, on a personal level, I have always felt a distinct sense of gratitude and appreciation for all of my blessings. Having been born in the year 1969 in Brooklyn, my lot in life is no doubt much different than had I been born in 1942 in Warsaw, or 1939 in Krakow, or Bialystock, or any one of the countless villages and shtetls in Poland and throughout Europe. I am not sure by what stroke of luck I was fortunate enough to have been born where and when I was, but it could have easily been much different. I will leave it up to the rabbaim and philosophers to help explain the process of where and when a soul is chosen to enter this world, but suffice it to say I consider myself greatly fortunate and I acknowledge those who were not.

Second, let us all remember that there is 1,000 years of Ashkenazic Jewish tradition in this part of the world. So much of our tradition, culture and history today has its roots in Poland and surrounding countries. Ashkenazi Jews cannot deny the impact of the Polish and Galician traditions on who we are and how we live our lives.

Third, we owe respect and honor to those who are no longer here. To those who lie in the countless graves, marked and unmarked, mass graves, or even non-existent graves (i.e. ashes), across the entire country and continent. Who will visit, who will pay respect if not us? Who will even remember them, not as numbers but as individuals? How often do we visit the kever of a loved one who is buried here in the US or Israel? Do the kedoshim of the Shoah deserve any less?

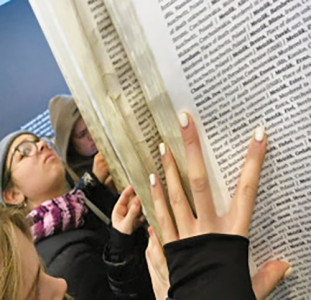

But it goes even deeper than remembering those who can be remembered. What about those who we cannot? One of the exhibits in the Auschwitz museum is a series of large printed pages, all bound together to create a “book” that runs nearly 50 feet from beginning to end. The names were compiled under the guidance of Yad Vashem, and are supposed to represent all those who perished in the Shoah. I counted approximately 250 names per page, with over 16,000 pages (no I did not count the pages – fortunately they were numbered). That equals approximately 4 million names. As our group peered intently into the book looking for some connection to family names and origins, the horrifying reality of this calculation led me to think, “What about the other 2 million?” After nearly 80 years and countless hours of research, documenting and compiling, there are still 2 million souls for whom we cannot even account. How can that be possible? How do you remember someone whose existence is a mystery?

I will share another anecdote that illustrates this point. Our guide shared with us a photo that was smuggled out of Auschwitz, showing a group of approximately 50 individuals as they were taken off the cattle car and awaiting selection. After the war, as Jews were attempting to identify and catalog who survived and who was lost, the question was asked of a number of survivors if they could identify anyone in the photo. Not a single person could identify anyone in the picture. Not a single person could identify anyone in the picture. Think of how many people know you in this world: 100, 250, 500? Think of the connections you have to others (i.e. six degrees of separation) and how many people can at the very least identify your existence. The connections for each of us today must number into the hundreds or thousands. What level of destruction would need to occur for every trace of your life to be erased so that nobody could even remember that you had existed? It is incomprehensible. How do we remember those who we never even knew existed?

Fourth, and perhaps the most important reason I went, is because we have a duty to make sure what happened is remembered, and is handed down to the next generation. As time moves forward, the eyewitness testimonies become more distant, and the numbers of direct survivors become fewer with every passing year. Future generations will need to begin to learn these stories based upon what they have been taught from a secondary source, not what they have been told from survivors. As we pivot to this next phase of Holocaust education this is a seminal moment in our collective story. We bear the responsibility to ensure the transmission of our history continues forward.

So many of us have grown up learning and reading about the Holocaust. It has become ingrained in our collective conscience as Jews. We study it in school, we read about it in books, learn about it from films, and pause to remember it on Yom Hashoah. For most of us, the Holocaust is relegated as history in our collective past, a static reality in a world and place long long ago, to which very few of us can relate. We suffer from a bit of Holocaust “fatigue” – another Holocaust story, another Holocaust book, another Holocaust memorial. But after spending one week in Poland, what becomes more clear than ever before is its brutal reality and visceral tangibility – its present nature. It is still very much an open sore and gaping wound across the face of Poland and much of Eastern Europe. See the reality of the mass graves in countless fields and forests around Poland, the Umschagplattz of so many cities, the death camps of Majdanek, Auschwitz, Treblinka, just to name the few that we visited, each with their own unique testimonies

to the horrors of the Shoah. See the endless memorials, plaques, monuments and sculptures that dot the country. Realize that for every one you see there are countless thousands more across the vast space of the country, only to be multiplied again and again across surrounding areas of (formerly) Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Germany, Ukraine, and on and on and on.

Too often in studying the Holocaust we focus on numbers and figures alone. Here 18,000 Jews were shot; here 2,000 were burned alive in their shul; here 360,000 were killed in a concentration camp. In reducing human beings to mere numbers we fail to appreciate the sense of the individual. Each precious soul who perished in the Holocaust had their own individual world that was unique to them – their personal hopes, dreams, aspirations, memories, stories, loves, each just as unique as mine or yours. While these individual worlds can obviously never be replicated, perhaps being close to their last physical location in some small way helps to preserve and honor their memory and all they held sacred.

And so at the end of our journey I walked away with a deeper appreciation and some answers to the question of “why.” But one thing I had not counted on was the positive side of the story. Of course I was encouraged by the stories of Jewish and Polish heroes: Janusz Korczac, the

father of the orphanage in the Warsaw ghetto who accompanied his orphans to Treblinka rather than accept an offer for escape; The Rav of Pietrokov who met his end with his congregants, but who ultimately was the father of the first Chief Rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Meir Lau; The heroes of the Warsaw ghetto uprising; The story of the founding of Daf Yomi by Rabbi Meir Shapiro in Yeshivat Chachmei Lublin; The story of the partisans who fought out of the forests of Poland; The famous story of Oskar Schindler and his factory; The righteous gentiles who risked everything to help a Jew. These are just a few of the stories of heroism and hope.

But on a deeper personal level, nothing gave me more courage and hope for the future than the 30 young women from our AMIT group who were with us on the trip. As they took in one gut wrenching scene after another, the sense of maturity, courage and strength that emanated from them was undeniable and empowering. Each student shared stories of their families and the experiences of their grandparents / great grandparents, with one story more amazing than the next – stories of heroism, sacrifice, incredible resolve and equal amounts of good fortune and luck. As I watched these young women walk out of the camps with arms locked together, I came to ultimately understand the real reason why I went to Poland. For it is our precious daughters, including my Julia, and all of our collective children, who will carry these memories forward and honor those who were lost. They represent our present and our future. The words “Am Yisrael Chai” are alive and well inside each and every one of them.

By Adam Fried