The Mishna on Shevuot 32a discusses an oath to compel testimony. Suppose I know that two people witnessed an event, and their testimony would help in my case. They have a biblical obligation to testify (Vayikra 5:1). They can swear an oath denying knowledge of the event, but are liable for a false oath. Now, two witnesses are only effective as a set. The Mishna therefore states that if both witnesses deny together, they are both liable. If they deny it sequentially, then only the first is liable, because without the first, the second’s testimony isn’t dispositive.

Rav Chisda (third-generation Amora, Sura) said this Mishna discussing simultaneous denial works within Rabbi Yossi HaGlili, who maintained that it’s possible for two events to precisely coincide. Rabbi Yochanan (second-generation Amora, Teveria) states that this simultaneity could arise via תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר. Words spoken within a certain timespan of an initial utterance are associated with that initial utterance.

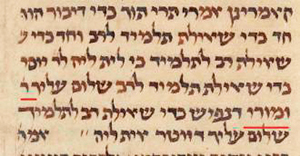

Much later, Rav Acha of Difti (seventh-generation, Mata Mechasya) asked Ravina II how this could work. After all, as centrally defined in in Bava Kamma 73b, תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר is either a teacher’s greeting of a student – שָׁלוֹם עָלֶיךָ, which is five syllables or a student’s greeting of a teacher — שָׁלוֹם עָלֶיךָ רַבִּי וּמוֹרִי, which is ten syllables. (Note that the additional ומרי / ומורי is what the Vilna, Venice and Soncino printings have, alongside the Florence 8-9 manuscript; however, Hamburg 165, Munich 95 and Escorial just have רַבִּי, for seven syllables. See also Sanhedrin 98a, Berachot 3a and Taanit 20b for greetings of varying lengths.) Regardless, one witness saying שְׁבוּעָה שֶׁאֵין אָנוּ יוֹדְעִין לָךְ עֵדוּת is at least 12 syllables — more if you include two sheva nas — so how could the second one’s denial relate to the initial question? Ravina II answered that the תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר only needs to be to the preceding witness’s denial, and it’s all considered continuous.

Difficulties With Rabbi Yochanan

Several aspects of this sugya trouble me. Regarding Rabbi Yochanan: (a) Based on scholastic generations, it’s slightly strange for him to follow Rav Chisda in their dispute. Perhaps the logic and framing of the sugya works better with Rav Chisda taking the lead. Further, (b) the typical תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר involves retracting or modifying one’s own initial words. It occurs when one hasn’t fully completed his thought, and so can add, or say, “Oops, I misspoke, and meant X.”

Finally, (c) we’d expect Rabbi Yochanan to say the same in the Mishna’s reisha in the parallel Yerushalmi Shevuot 4:3, but he doesn’t. Instead, the analysis appears in the seifa of the Mishna, כָּפַר אֶחָד וְהוֹדָה אֶחָד הַכּוֹפֵר חַייָב. Straightforwardly, the Mishna is describing a case where one of the witnesses denied knowledge and the other admitted knowledge. Only the denier blocks, so he’s liable. According to Rabbi Yochanan’s Amoraic student, Rabbi Yossi, perhaps because it does not say harishon chayav, the Mishna deals with both witnesses initially denying, but then one retracts. The Mishna effectively teaches that even in a sequential case, either person can retract an initial denial and leave the other as the sole denier. lSo long as we’re within תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר, a retraction is possible. (Different girsaot / interpretations would lead us to discuss how it’s תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר of the same witness or even the other witness.) The Talmudic Narrator in our Bavli (Shevuot 23b) suggests something similar, but not as a primary sugya. Rather, it grapples with why it’s necessary to say this according to Rabbi Yochanan, once we’ve already established it above.

We often see free-floating statements of Amoraim or partly developed sugyot, with ambiguity expressed by either the Talmudic Narrator or named Amoraim as to which portion of the Mishnah it pertains. See, for instance, אִיכָּא דְּמַתְנֵי לַהּ אַרֵישָׁא, וְאִיכָּא דְּמַתְנֵי לַהּ אַסֵּיפָא, in Pesachim 96b, Ketubot 24a and 34b and Bava Kamma 112a. Some scholars suggest that often, statements from any Amora in Eretz Yisrael get reported in Bavli as “Rabbi Yochanan.” I’d suggest that here a free-floating Rabbi Yochanan statement was repurposed from the seifa to provide a counterpoint to Rav Chisda on the reisha.

Difficulties With Rav Acha miDifti

The attack from Rav Acha of Difti also troubles me. As Tosafot note, perhaps the second witness began speaking later but overlapped with the first witness, so there’s still תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר. They reject it because this is atypical and two voices cannot be heard at once.

I’d add that while תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר is standardized as the typical speech rate of about three seconds, perhaps the first witness speaks faster than average. The current average speaking rate among Hebrew adults is 154.11 words per minute, or 5.6 syllables per second, with older adults speaking more slowly.1 Maybe greeting one’s teacher is done at a slower, respectful rate, while testimony might occur in rapid-fire Hebrew. This has its conceptual parallel in someone becoming impure in the Beit Hamikdash, who must leave via the shorter path. Abaye grapples with whether this fixes a standard time measurement, and someone leaving hastily via the longer path is liable (Shevuot 17b).

Moreover, must a witness utter all these syllables to be liable? Imagine the plaintiff asks two witnesses to testify. Each says, “We don’t have testimony for you.” He says, “I administer an oath to you.” Then they each say, “Amen”. We needn’t imagine this, since it’s the second type of שְׁבוּעַת הָעֵדוּת menitoned in the Mishna (Shevuot 31b). “Amen” is only two syllables, which is less than a greeting. Finally, if Rabbi Yochanan never said his statement, how could Rav Acha MiDifti attack it?

Transferred Sugya

Rav Acha MiDifti’s question to Ravina II also occurs in Makkot 6a. The preceding Mishna stated that two witnesses can render even a set of 100 witnesses as eidim zomemim— conspiring witnesses. Fourth-generation Rava clarifies that these 100 form a set by testifying תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר. Rav Acha MiDifti asks Ravina: “From the end of the first witness’s testimony to the beginning of the 100th’s testimony is surely more than תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר!’ Ravina responds that the תּוֹךְ כְּדֵי דִיבּוּר is between each witness.

Makkot 6a seems like the primary sugya. The relevance of the question and answer seem much stronger. It’s a shorter sugya, just containing this exchange, instead of being embedded within a larger sugya. Also, Rav Acha MiDifti and Ravina II are closer in time and space to Rava than to Rabbi Yochanan.

We often see an Amora make the same statement, or even two Amoraim have the same exchange, in several sugyot. I would not rule that they actually repeated it in different contexts; people have their respective positions, and they would go through the same song and dance any time an idea comes up. Indeed, I’ve seen this occur many times among the participants in the Daf Yomi chabura in Rinat. Even so, it’s plausible and likely that some sugya fragments have been transferred by the Talmudic redactors2 to new contexts because they found it relevant— a phenomenon called ha’avara. If so, Rav Acha MiDifti’s attack could indeed make more sense in Makkot, the primary sugya, than it does in Shevuot.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes Natural Language Processing, LLMs, and the Jewish Digital Humanities.

1 See “Speaking Rate among Adult Hebrew Speakers: A Preliminary Observation,” Ofer Amir, Annals of Behavioural Science.

2 Presumably here post-Ravina II.