Why did Yaakov fear for Binyamin? In sidrat Miketz, he didn’t want to send Binyamin along with Reuven to Egypt, lest harm befall him (וּקְרָאָ֤הוּ אָסוֹן֙) on the journey. On Ketubot 30a, Abaye (fourth-generation Amora, Pumbedita) understands this as harm at the hands of Heaven (בִּידֵי שָׁמַיִם), using that to explain Rabbi Nechunia ben HaKaneh’s position. Rabbi Abba bar Ahava (presumably #2, the fourth-generation Amora of Mechoza, Rava’s locale, rather than #1, the second-generation Amora of Pumbedita, who’s too early) objects. How do we know that Yaakov was concerned with cold and heat (צִינִּים וּפַחִים) which are in the hands of Heaven as opposed to harm at the hands of man (בִּידֵי אָדָם), namely a lion or bandits? The Gemara reverses which is בִּידֵי שָׁמַיִם and בִּידֵי אָדָם based on Tannaitic sources. Regardless, I wonder if we can relate this debate to perceptions of Yaakov mindset, as Yaakov was told that a wild animal had eaten Yosef and perhaps suspected the brothers, but also saw the Divine plan in action, removing Yosef from him.

Because peshat is innovated each day (Rashbam to Bereishit 37:2), here’s another suggestion for Yaakov’s concern. In sidrat Balak, we encounter Bilaam’s she-donkey. Had he not heeded her words, and diverted from the path, Bilaam would have lost his life. And, Bilaam’s donkey wasn’t just present in that Biblical scene. Pirkei Avot (5:6) relates that her mouth was created at twilight on the last day of Creation. While on a straightforward level, that refers to the deviation from the natural order being baked into Creation itself, in Pirkei deRabbi Eliezer (chapter 31), we discover that the donkey saddled by Avraham preceding the Binding of Yitzchak was the son of that she-donkey created at Creation’s twilight. (Thus, the definite article in הַחֲמוֹר.) And, that same male donkey was the one ridden by Moshe when traveling back to Egypt after sending his wife and children back to Midian, and the same donkey will be ridden by mashiach. Thus, the male donkey and its mother are long-lived, and its speaking mouth was already created. Yaakov might have feared lest the she-donkey call out to him—ukra`ahu ason—placing him in mortal danger.

Sefardi readers are confused at this point, while Ashkenazim are rolling their eyes. Yes, I’m kidding but, in my defense, there are derashot based on ayin/aleph similarity (e.g. Berachot 32a). The switch-off here is between thav without a dagesh and samech, both of which Ashkenazim pronounce as /s/.

Asi vs. Ashi?

This brings us to Ketubot 33b. Rav Ashi (sixth-generation Amora) suggests that flogging is more severe than the death penalty, based on a statement by Rav (first-generation Amora) that had they flogged Chanania, Mishael and Azaria rather than threatening them with burning, they would have capitulated to worshiping the idol. Then, אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב סַמָּא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב אַסִּי לְרַב אָשֵׁי וְאָמְרִי לַהּ רַב סַמָּא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב אָשֵׁי לְרַב אָשֵׁי. Rav Sama son of X objects to Rav Ashi that we might distinguish between flogging with a limit (as per the Torah’s restriction) to flogging with no limit.

Who is Rav Sama’s father? The Talmud records two competing traditions (וְאָמְרִי לַהּ), that his father was Rav Asi or Rav Ashi. Rav Ashi seems more reasonable, for then Rav Ashi’s son objects to Rav Ashi. Rav Asi seems the less reasonable option, for Rav Asi (of Hutzal) was a first-generation Babylonian Amora, so his son is too early. Could we change the title to “Rabbi” Asi, obtaining the third-generation Amora who made aliyah from Bavel to Israel? Manuscript evidence is absent. Regardless, his son is too early to interact with Rav Ashi. Were these our options, I’d posit that “Rav Ashi” was original, and a shin/samech switch-off occurred, as an oral error.

Athi vs. Ashi!

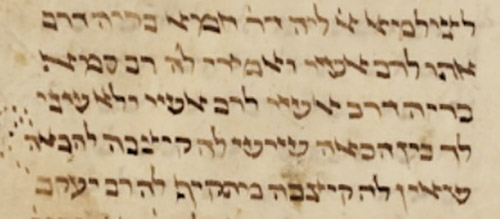

However, when we examine manuscripts, we see that Rav Asi hardly appears! Instead, the alternates are consistently Ashi/Athi – אשי/אתי (with a few variant Athi spellings1 ).

Rav Hyman, in Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim has an entry on Rav Asi, the colleague of Rav Ashi. He writes that this late Amora is actually always Rav Athi, according to Dikdukei Soferim. Hyman helpfully lists and discusses many such instances of this Rav Athi, which would otherwise confuse us as violating chronological order. He sat before Rava in Shabbat 95b, reporting on what he’d heard of the measure of a hole in an earthenware vessel, and Rava modifies his suggestion. In Eruvin 39b, he modifies Rava’s suggestion. In Eruvin 64b, he asks Rav Ashi why one must pick up pieces of bread on the ground, given that a Biblical verse indicates that they, too, are used for witchcraft. In Ketubot 8a, he visits Rav Ashi’s house and is honored to recite the six (rather than seven) blessings at Mar bar Rav Ashi’s wedding.

How did this consistent error happen? Earlier printings (e.g. Venice) have Rav Athi correctly. If I recall correctly from shiur, Rav Shlomo Hakohen of Vilna, who edited the Vilna Talmud printing, proofed the galleys of the Vilna Talmud based on examining manuscripts. Descendants proudly relate that he was such a genius that he did so by memory. Unfortunately, this led to various oral errors. Pronouncing a /th/ as a /s/ is one such error. (Note that where earlier printings had already erred and misinterpreted the ת as a ח, thus “Rav Achi,” Bava Metzia 90b, Eruvin 10a, or corrected it to Rav Ashi (Chullin 141b), the Vilna Shas propagates that error.)

Who Cares?

What is the impact of this? I’m reminded of Ketubot 19a, where Rabbi Ami says an non-proofread scroll can only be maintained in one’s house for thirty days; afterwards it’s a violation of allowing עַוְלָה/injustice to dwell in your tents (Iyov 11:14). Rashi explains scroll as Tanach, and Rosh suggests this is only because those were the only scrolls available in Rabbi Ami’s time. However, this shouldn’t exclude books available to us. This is because, Rosh writes, if one finds an error in a Gemara or a halachic work, he might come to permit the forbidden or forbid the permitted, and there is no greater avla than that!

I feel that rabbinic biography can impact Halacha. For instance, we might say hilcheta kebatrai, we rule like the later authority, if we knew that what seems first-generation Rav Asi was really the late Rav Athi. Therefore, perhaps we should consult Rav Hyman’s list, take a pen and correct all Athi instances in our Talmuds. Though why am I suggesting this here more than any other week, where I discuss alternate manuscript variants? I suppose because those were speculative, while this particular consistent mistake is quite solid.

1 Or perhaps Atti. An interesting exception is Munich 95 with אשי / איתי, though with an Ashi / Asi alternation in the target, but we’ll ignore that. Another is Sankt Florian: Cod. XI 84, which has an איתי / אסי alternation.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.