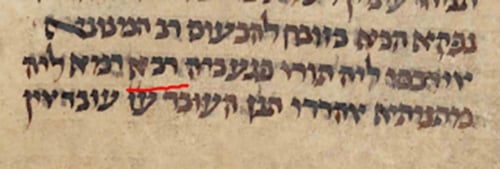

ויִּקַּח סֵפֶר הַבְּרִית וַיִּקְרָא בְּאָזְנֵי הָעָם וַיֹּאמְרוּ כֹּל אֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר יְדֹוָד נַעֲשֶׂה וְנִשְׁמָע

(שמות כד:ז)

“He then took the Book of the Covenant, and read it in the ears of the people. They said, ‘All that Hashem has spoken, we will do and we will listen.’”

It is written in Gemara Shabbos (88a), Rabbi Elazar said: “When Bnei Yisroel declared in Sinai ‘We will do,’ before “We will listen,” a bas kol emerged and said: ‘Who revealed to my children this secret that the angels (malachim) use?’” As it is written: “Bless Hashem, His angels, the strong ones, which carry out His word, to hear the voice of His word,” (Tehillim 103:20). First, the malachim carry out His word, and after that they listen to His voice.

Zera Shimshon asks: How is it possible to “carry out His words” before they hear what those words actually are? If they don’t know what the words are, how can they be carried out?

He also asks: Why acting only after hearing is viewed as less ideal, and what elevates the practice of doing before hearing to a higher status?

Zera Shimshon explains in light of a midrash (Yalkut Shemoni, remez 587) that Hashem rewards even a non-Jew who learns Torah, but he receives less reward for his learning than the Yisroel, Kohen or Levi since he is not commanded to learn, and learns only voluntarily. This illustrates that someone who performs the mitzvos out of obligation receives greater reward than one who engages in them voluntarily.

The logic behind this is quite simple. It stems from the concept of obedience and struggle. When someone is commanded to do an action, it involves a level of commitment, obligation and strength to triumph the yetzer haras and negative forces that try their best to hinder, obstruct and prevent a person from doing a mitzvah. This person might face inner resistance or sometimes external challenges in fulfilling the commandment. Overcoming these hurdles to adhere to Hashem’s will demonstrates a deep level of submission to Hashem to undertake the battle and dedication to gather his strength to be victorious.

In contrast, someone who performs the action voluntarily, while certainly praiseworthy, does not experience the same degree of struggle against obligation or the challenge of submission to Hashem. The commanded action is a test of one’s faith and devotion, and being that it is more difficult, the fulfillment of such a mitzvah is more valuable in the eyes of Hashem.

Reflecting on the distinction between performing a mitzvah obligatorily versus voluntarily, Zera Shimshon reinterprets the idea of, “We will do before we hear.” Initially, it seemed to suggest—acting before knowing the specifics of the mitzvos—yet this approach is impossible. Without knowledge of Hashem’s expectations, accurately fulfilling His will is impossible! Zera Shimshon, therefore, re-explains it to mean, “We will do before we hear that we are commanded to do it!” The deeper understanding—as Zera Shimshon explains—is that we agreed to receive reward as if we will fulfill the mitzvos not because they have been commanded as such, which is more difficult, but from an understanding that this is Hashem’s wish. This shift emphasizes that seeking reward is not our ultimate goal and the driving force behind our performing the mitzvos; rather, our actions are motivated by a love for Hashem and a desire to meet His expectations. Period.

In adopting this mindset, our service to Hashem mirrors that of the malachim, who perform their duties without any expectation of reward. They only do it to sanctify Hashem’s name.

In this context, Zera Shimshon explains a Gemara that is written shortly after the one previously mentioned. This segment of the Gemara recounts an event where a heretic observed Rava engrossed in his study of a sugya to such an extent that Rava, unknowingly, inflicted pain upon himself by pressing his fingers under his thigh, causing them to bleed without his realization. The heretic confronted Rava—criticizing the impulsive nature of his people for acting before listening—suggesting that one should first understand and then decide if they are capable of observing the commandments before accepting them. Rava’s response highlighted the distinction in their approaches to faith; he cited a pasuk from Mishlei (Proverbs) 11:3, contrasting the integrity that guides the faithful to their completeness with the ruin brought upon by the treachery of the faithless.

Zera Shimshon asks: What is the meaning of Rava’s statement “that guides their faithful to their completeness?” What completeness is he referring to and, secondly, how does Rava’s lack of feeling pain—despite sitting on his hands—relate to the concept of being complete?

In Pirkei Avos (perek 1, mishna 3), it is written that Antignos of Socho, who received the tradition from Shimon Hatzaddik, taught: “Do not be like servants who serve the master to receive a reward; rather, be like servants who serve the master without the expectation of reward.” The Avos D’Rebbi Nassan elaborates that this teaching led the Tzeddukim and Beitussim to deviate—as they couldn’t fathom that the highest and most complete form of serving Hashem is to exalt Hashem’s name, devoid of any personal benefit—and that one must strive to serve Hashem from a place of pure devotion and love, that transcends the natural human inclination to seek personal benefit from one’s actions and only focus on Hashem’s glory. Upon hearing Antignos’s teaching, they abandoned traditional Judaism to establish their own diluted interpretation that won’t interfere with their self-centered and selfish way of thinking of “What’s in it for me?”

Serving Hashem with a focus solely on Him is deemed the epitome of completeness, as it is an act done entirely for Hashem, devoid of any self-interest. This notion of selfless devotion was embodied by Rava’s study, where he was so absorbed that he remained oblivious to his own pain.

According to Zera Shimshon, there is another difficulty in the incident of Rava and the Tzedduki that we can understand. Why did it bother this heretic so much, and why was the heretic so hostile toward Rava? Why couldn’t the heretic just “live and let live?”

The answer is that the heretic was deeply troubled by Rava’s intense dedication to his studies—to the point of self-injury—because Rava’s selfless devotion to serving Hashem starkly contradicted the heretic’s own beliefs. Rava’s passionate engagement in his learning—completely disregarding personal benefit or comfort—fundamentally contested the heretic’s beliefs. This made him feel as though his own faith was under attack and, therefore, prompted the heretic to verbally confront Rava.

The concept of serving Hashem purely for His sake—without seeking personal benefit—might appear distant from our everyday experience, yet this is not necessarily the case. Throughout our daily lives, many individuals perform acts not for personal advantage but simply because they are the correct actions to take. For example, individuals engage in volunteer work for charitable causes, spend significant time offering advice to others and defend those who are being bullied without any expectation of reward. While it’s true that Hashem acknowledges and rewards even the smallest acts of goodness, the motivation behind these actions is not the anticipation of reward; rather, it stems from a genuine recognition that these actions are inherently right.

(Adapted from Zera Shimshon, parshas Mishpatim, derush 10)