The anniversary of Theodor Herzl’s convening of the First Zionist Congress is cause for celebration; however, the ongoing battle to secure Jewish self-determination is far from over.

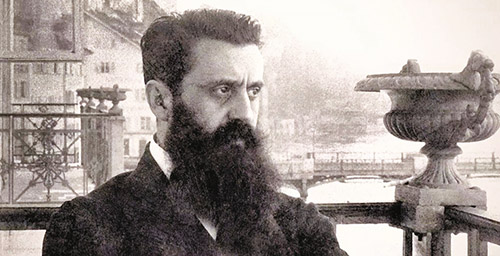

The Zionist movement is throwing itself a party. This week marks the 125th anniversary of Theodor Herzl’s convening of the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. The occasion has caused some controversy in Israel for what some think is the World Zionist Congress’ lavish spending on a program that will be unavailable to the public since most of it wasn’t livestreamed. Whether or not those criticisms are fair, interest in the commemoration outside of the organized Jewish world seems minimal. Indeed, other than as a photo opportunity for Israeli President Isaac Herzog to recreate Herzl’s famous pose on the balcony of the Hotel Les Trois Rois looking out over the Rhine River, few will pay much heed to the event.

Still, the 125th anniversary of modern Zionism is an apt movement for reflection on just how far Herzl’s idea has gone since he willed it into existence. Most importantly, it’s vital for those who care about the fate of the Jewish people to understand a troubling conundrum that points to both Herzl’s realism and where he was wrong.

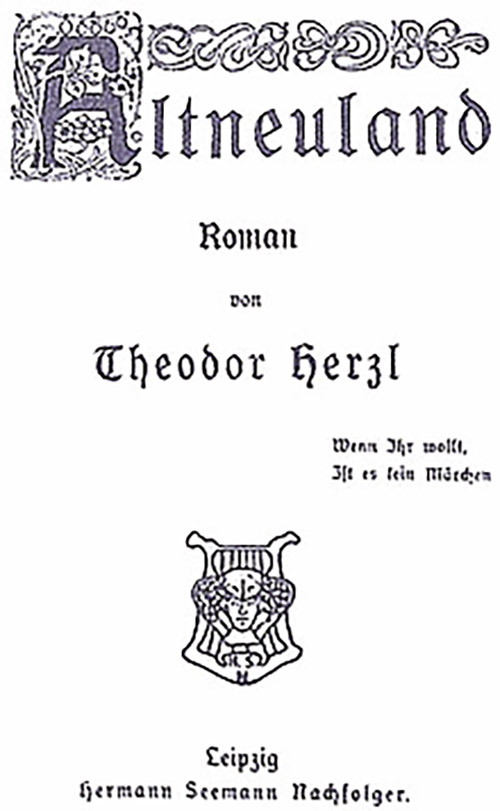

Zionism enjoyed unprecedented success with the recreation of Jewish sovereignty in the land of Israel right on schedule with Herzl’s prophetic diary writings. The Jewish state he envisioned in both the short book he wrote the year before Basel—”The Jewish State”—and a futuristic novel he penned five years later—”Altneuland” (“The Old New Land”)—didn’t merely come into existence, despite the skepticism and often bitter opposition of the non-Jewish and Jewish worlds. It thrived and grew into a regional superpower with a First World economy that is home to almost half of the world’s Jews and grows stronger day by day.

Indeed, for many Israelis, the notion of a Zionist movement seems antiquated. They understandably think that Zionism is something you are reminded of when you visit a history museum. They see the state Herzl dreamed of as an incontrovertible reality and the conflicts of the modern Middle East—in which Israel has both enemies and allies—as far removed from the theoretical debates in which Herzl was forced to engage. From that frame of reference, the continued existence of some of the entities that trace their roots to Basel and even the argument about a Jewish state are like fossilized remnants of the 19th century stuck in amber.

However remote the events of August 1897 may seem to us, the presence of several hundred demonstrators outside the WZO event is a reminder that the debate about Zionism is not over. Israelis may think the idea of erasing their country from the map is a sick joke. But to the Palestinians, whose national identity is inextricably linked to their century-long war against Zionism, as well as the vast number of people around the world who—whether because of solidarity with fellow Muslims or leftist ideology—oppose Zionism, the goal of undoing Herzl’s vision is something they not only applaud but think can be achieved.

That this is so points directly to one flaw in Herzl’s otherwise prescient understanding of the world in which he lived.

Though many in his time believed in the idea that progress was leading the Jews towards greater acceptance and freedom in the non-Jewish world, Herzl grasped that the arc of history was heading in a very different direction. He understood that the rising tide of antisemitism that was bubbling up throughout Europe in more enlightened places like France, as well as in reactionary authoritarian regimes like the Russian empire, wasn’t going to be stopped by either assimilation or the forces of modernism. That led to his conviction that without a state of their own, Jews would not only continue to suffer from discrimination and violence but that their plight would grow worse.

Neither Herzl nor the Basel Congress invented Zionism—the concept of a Jewish state or the idea of the inevitability of the return of the Jews to their land. Contrary to those who wrongly claim that Judaism is merely a religion and that opposing Israel’s existence has nothing to do with antisemitism, the connection to the land of Israel is an integral part of Jewish faith and part of the daily liturgy. The longing for Zion is as old as the Jewish people, and the hope of returning to it had sustained Jews throughout millennia of exile. What Herzl did do was mobilize and organize a movement that made the realization of those hopes possible.

Days after the Congress concluded, Herzl wrote in his diary: “At Basel I founded the Jewish State. If I said this out loud today, I would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will perceive it.” Given that the U.N. partition resolution that mandated the creation of a Jewish state was passed in November 1947 occurred just more than 50 years later, Herzl was proven right. It came too late to save the 6 million Jews who perished in the Holocaust, who would have had a place of refuge had Zionism achieved its great victory earlier. Yet that proved just how correct Herzl’s sense of urgency had been.

There is, however, one element of the problem that Herzl didn’t understand. He was right to see homelessness and the lack of political power as elements that would lead to tragedy. Yet he also wrongly believed that once a Jewish state had been created, antisemitism would dissipate. While Zionism gave the Jews a badly needed mechanism with which to defend themselves, it could not eradicate the virus of Jew-hatred.

Antisemitism has not only survived but thrived in the last 125 years as it attached itself like a parasite to a variety of different political movements—fascism, Nazism, communism, and in our own day, Islamism and woke neo-Marxism—all of which have helped perpetuate hate for Jews. Instead of eliminating the raison d’être of anti-Semitism, Israel has become the focus of it.

Anti-Zionism is not merely masquerading as something other than that hatred; it is the essence of 21st-century antisemitism. Its premise is not only to deny rights to the Jews that no one would think of denying to any other group. It is the mechanism by which intimidation, delegitimization, violence and terrorism against Jews are rationalized and justified.

That is why Jew-haters demonstrate against a commemoration of Basel, as well as calling for the abrogation of every milestone along the path to Jewish statehood—the 1917 Balfour Declaration and the 1947 Partition Resolution. Their global antisemitic BDS movement aimed at stifling the Israeli economy has largely failed. Nevertheless, it has provided a framework by which Jew-haters can not only organize themselves but do so while pretending to be advocates for the human rights of Palestinians, whose goal is to eliminate Israel.

It has also allowed the same world body that authorized Israel’s creation—the United Nations—to be the stronghold of those who believe, not unrealistically, that they can libel Zionism as racism and eventually isolate and ultimately destroy the Jewish state.

That is why advocacy for Zionism—the national liberation movement of the Jewish people—is not only relevant today; it is absolutely necessary in order to preserve not just Herzl’s legacy, but to fight back against a movement whose goals could only be achieved through the genocide of Israel’s 7 million Jews.

Though Herzl was wrong to think that a Jewish state would solve the problem of antisemitism, he was right to believe that one was necessary, as well as a just solution to the plight of Jews in Europe and the Middle East where they would never be fully accepted as equals or safe.

Long after the rebirth of Jewish sovereignty in Israel has become a reality, it may seem odd that we must continue to discuss the right of the Jews to their state. The triumph of Zionism was something that few Jews or non-Jews thought was possible in 1897. Yet as unthinkable as the destruction of the Jewish state is today, the fact that hundreds of millions, if not billions, of people believe its destruction is a good idea points to the persistence of antisemitism. Just as important, it should remind all people of goodwill—Jews and non-Jews alike—of the necessity for continued Zionist activism.

Jonathan S. Tobin is editor-in-chief of JNS (Jewish News Syndicate). Follow him on Twitter at: @jonathans_tobin.