In the November 12, 2020 edition of The Jewish Link, Rabbi Dov Emerson, director of teaching and learning at MTA, wrote an insightful piece entitled “When Extracurricular Isn’t Extra at All.”

In his article he basically affirmed the modern centrality in Jewish education of the total educational experience both inside and outside the classroom. As the following underscores, while this might appear to be a purely positive development, the introduction of extracurricular activities as a critical element of the admissions process at the top universities in America and abroad had in its origins a considerably less benign objective: to exclude, rather than include, otherwise qualified candidates for admission.

When Jake Rabinowitz was completing his junior year at his yeshiva high school in Manhattan in 1966, he was faced with the challenge of applying to college. He wanted to stay more or less local for his higher education, leaving himself with a rather limited selection of choices: the City College honors program, New York University and Yeshiva College. In the pre-internet days, he accordingly ordered by mail copies of each school’s catalogs as well as their admission packets. Jake’s older sisters—his only siblings with experience—suggested he consider applying to the prestigious local Ivy League school, Columbia College, located in Morningside Heights a mere 14 blocks from Jake’s home on the Upper West Side:

“I know a lot of Jewish guys who attend Columbia and I think you’re smart enough to get in. Why don’t you apply there also?” suggested Yvette, his oldest sister who had recently graduated from City College.

Jake received a similar suggestion from his Hebrew tutor who had recently graduated from Columbia. As a result, Jake added Columbia to his list of potential college destinations, reading whatever he could about the school. As the weeks went by, Jake gathered up and read through all the application materials and their detailed instructions.

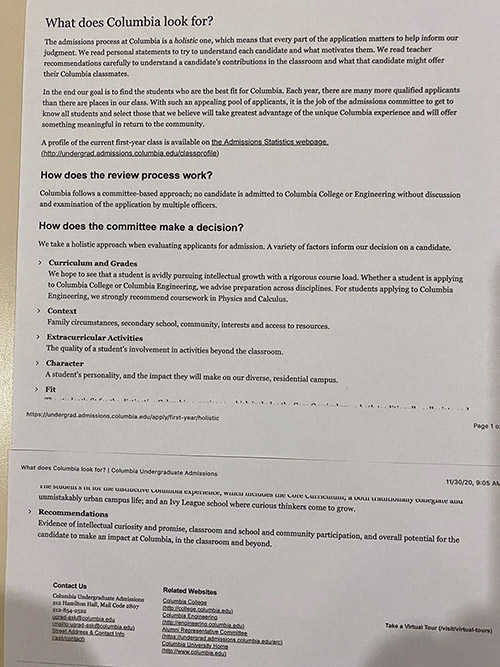

The Columbia packet was the largest of all: pages upon pages, each section printed on different colored paper asking him for detailed personal information: vital statistics, information concerning each parent and their countries of origin, educational background, occupations. In addition, Jake was asked to provide two recommendations from teachers and references from individuals who could vouch for his character. School transcripts were of course also required as well as test results (SATs and subject proficiency tests); the school also requested that Jake submit a one-page essay or writing sample.

Finally the school required Jake to provide a detailed listing of all extracurricular activities he had participated in, covering athletics and academics, civic, social and political activities. When Jake finished the Columbia application, he realized the school would know his entire “life story.” There would be little that the school would not know about him as they made their decision to accept or reject his application.

Columbia had declared to all applicants that they were seeking an entering class that year of “1,000 geographically diverse” qualified candidates for their incoming freshman class. As the last step in their process, each applicant would be required to schedule a short interview at the school in the fall of their senior year. As the months went by, Jake made sure he met all relevant deadlines. He scheduled his Columbia interview and dutifully visited the campus on the appointed day. Jake reminded the interviewer of Columbia’s stated goal to construct a “geographically diverse” freshman class.

“Well, if you want true geographical diversity,” Jake offered, “you probably need an applicant or two who live very close to the campus, in order to balance off those candidates from far away or abroad.”

The interviewer couldn’t disagree.

“If that’s the case, then I’m your man; I live only 10 blocks away from the college!”

By the April of his senior year, the results were in, and Jake had been accepted to all the schools he had applied to, including Columbia College, by now his first choice. As he reflected on the whole application process in the weeks that followed, he thought about how thorough the Columbia application process had been, gathering such detailed information on who he was—not just academically, but socially. What Jake did not know at that time was that the details gathered by Columbia from each applicant had as their purpose, the less-than-friendly objective of potentially excluding, not including, otherwise qualified candidates for admission to the entering class.

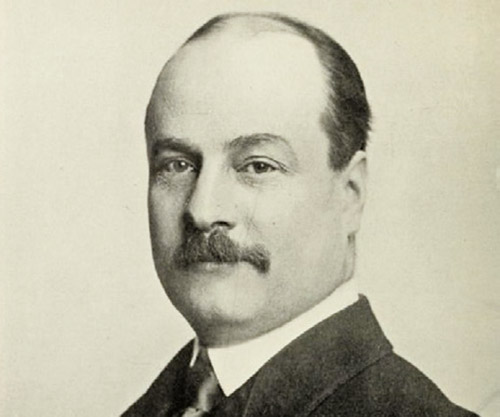

The reality was (of which Jake was also unaware, as were most people at the time) that Columbia College had been grappling for more than half a century with its own—it can only be called—“Jewish question.” As early as 1902, John B. Pine, the clerk of the board of trustees, had written to the formidable president of the university, Nicholas Murray Butler (1862-1947), cautioning him that, in the light of the increase in applications to the college by children of recent immigrant families,

“…we are in danger of being overwhelmed by the number of Jewish students who are coming to us, and who are certain to increase in number.”

Butler (the father of the College Board and the SAT) felt that Columbia was threatened by such increased “socially undesirable” Jewish enrollment, but as things stood there was little he could do about it at that time. First, the school could not afford to limit enrollment due to budgetary concerns. Second, at that time the school’s admission process consisted of the candidates’ simply passing one of three tests: Columbia’s own admissions exam, that of the New York State Board of Regents or that of the College Entrance Examination Board. The admission standards were purely objective in nature and, as a result, the Columbia crisis directly followed from too many socially undesirable Jews passing the tests!

Butler and his supporters on the board literally felt during the ensuing decade (1910-1920) that New York University and City College were better choices than Columbia for the Jewish student body. In response to his continuing “Jewish problem”, Butler finally decided to consolidate the admissions process for the University, resulting in a change in admissions policy dating roughly from 1910. From then on,

“… {T}he candidates’ suitability (for admission) {will} be determined not just on the basis of exam results but also on an evaluation of high school records as well as interviews.”

The effect of adding some administrative subjectivity to the admission process did not solve Columbia’s problem entirely. Jews continued to apply in large numbers and probably reached at its height 20% of the entering class in the pre-World War I years. Butler ceaselessly struggled to deal with this “vexing” issue, even feeling it necessary in 1914 to assuage respectable gentile families in New York that Columbia’s Jewish character “had been exaggerated.” Frederick Keppel, dean of Columbia College, in fact authored a pamphlet entitled “Columbia” (circulated to all prospective applicant families) that addressed the Jewish issue succinctly. First, he stated rather dubiously that the proportion of Jewish students was decreasing rather than increasing. Second, Keppel opined that “the Jews who did come to Columbia tended to be desirable students in every way,” and could be deemed “entirely satisfactory companions.”

Whether formal communication such as Keppel’s to potential students’ parents had any impact on Columbia’s applicant pool is unclear. The bottom line was that as the United States entered the Great War, Butler finally addressed his Jewish problem definitively. Keppel left Columbia to become assistant secretary of war in Washington, and his place as dean of the college was taken by Herbert Hawkes, a mathematics professor whose job included supervising the director of admissions. Under Butler’s guidance, Hawkes began to flesh out those extra-academic criteria Columbia would add to their admissions process that could justify the rejection of Jewish applicants. Over the next three years, the college set out the following criteria:

In 1917, the college formally listed the new, desirable qualifications for admission: intellectual ability (paramount) and qualities of character and capacity for leadership (essential). The latter qualities were itemized as “native strength and uprightness, independence, initiative, capacity for cooperation, balance and sanity, public spirit and the ability to enlist others in work for the general good.” It is not a stretch to believe that, stereotypically and subjectively, Butler and his helpers on Columbia’s admissions committee likely felt that most Jewish candidates for admission would fall somewhat short of those difficult to achieve enumerated standards of character and achievement.

Butler finally decided as well in 1917 to expressly limit the size of the entering class to the college; he would employ the new combined criteria to select the “cream of the crop” among the capable applicant pool. According to one biographer, Butler did at the same time reject adopting any direct quota for Jewish students, feeling the admission committee had enough “ammunition” to keep “undesirables” to a minimum. The new process would look broadly at a student’s academic potential, personality and school achievements.

The final remaining Butlerian step to the modern application process (designed to exclude, rather than include undesirables) took place in 1920 when Butler ordered the admissions committee at Columbia to request from each candidate a slew of “non-quantifiable material.” The applicant would now be required to submit “school records and character recommendations, father’s place of birth and occupation, his own religious affiliation, his school activities (athletics, publications, musical organizations) and his patriotic activities, both inside and outside of school.” Thus the modern Columbia application took shape over years.

Columbia still admits large numbers of Jewish students each year and, it’s fair to say, they represent a good cross section of the American spectrum socially, politically and academically. It’s difficult to say that today after 100 years more are excluded than included as a result of details requested on the Butler-influenced application.

Author’s note: Jake in due course attended Columbia College and graduated with honors as a member of the Class of 1971. He only learned about the origins of the Butler-created “exclusionary qua inclusionary” application process in 2006 upon the publication of the excellent Nicholas Miraculous: The Amazing Career of the Redoubtable Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler by Prof. Michael Rosenthal, upon whose work the author has relied heavily for this essay.

Joseph Rotenberg, a frequent contributor to The Jewish Link, has resided in Teaneck for over 45 years with his wife, Barbara. His first collection of short stories and essays, entitled “Timeless Travels: Tales of Mystery, Intrigue, Humor and Enchantment,” was published in 2018 by Gefen Books and is available online at Amazon.com. He is currently working on a follow-up volume of stories and essays.