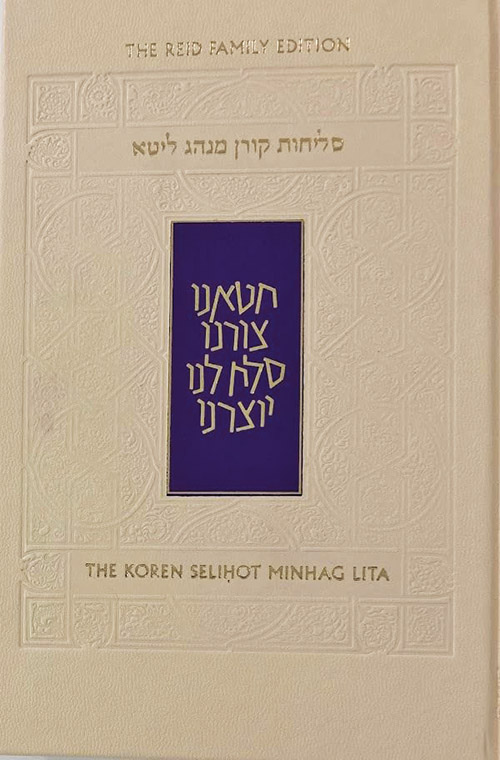

Reviewing: “The Koren Selihot Minhag Lita” by Rabbi Jacob J Schacter. Koren Publishers Jerusalem. 2022. Hebrew and English. Hardcover. 1314 pages. ISBN-13: 978-9657766682.

Saying you are sorry is never easy. That notion was a hit song with Elton John in his “Sorry Seems To Be the Hardest Word.” The song’s lyricist, Bernie Taupin said that the song explores a pretty simple idea and one he thinks everyone can relate to at one point or another in their life. That whole idealistic feeling people get when they want to save something from dying when they basically know — deep down inside — that it is already dead. It is that heartbreaking, sickening part of love that you wouldn’t wish on anyone if you didn’t know that it’s inevitable that they’re going to experience it one day.

While the song may be somewhat fatalistic in the dimension of the human element, there is never a fatalistic component when apologizing before God.

For our Sefardi brethren, they have been saying selichot, the penitential poems, and prayers for a week now. In comparison, Ashkenazim will not start until a week before Rosh Hashanah. Many of the selichot are written in dense, poetic Hebrew, which is not always easy to understand.

In “The Koren Selihot Minhag Lita” (Koren Publishers), Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter takes that dense Hebrew prose and adds his insights to them. Here, he has a most insightful running commentary on many of the selichot.

The book opens with his monograph about the selichot. Schacter is not just a brilliant scholar and orator, he also has his pulse on the human condition, and his explanations of the selichot — and the context of how and when they were written — add significant insights into these supplications.

Many of the selichot were written during the Crusades by Tosafists who saw their wives and children slaughtered before them. Selichot were written as villages plundered, as copies of once-in-a-lifetime seforim were being burned, and more. While Schacter’s commentary is not meant to be a feel-good guide; the catastrophes in which these selichot were written underscores how good we have it now.

While much of Elul is spent saying selichot, Schacter writes that selichot, in fact, was originally instituted to be recited specifically on fast days. They were later established as part of the liturgy for the Ten Days of Repentance, because the custom used to be to fast then.

The Chazon Ish is well-known for some of his stringencies. In selicha number 5 on avot k’gadil — like thick ropes —Schacter quotes a fascinating insight from the Chazon Ish, that one should relate to non-observant Jews in contemporary times with ropes and bonds of love. That approach was so radical at the time, that some accused the Chazon Ish of being too liberal.

As noted, many of the selichot were written by Tosafists, who were able to encapsulate large swaths of meaning, often with biblical references, in a few terse words. Sara Daniel did the translation and made the piyyutim much more accessible to the English reader.

Given that we spend weeks on selichot, anything to make that experience more meaningful is a welcome edition. And to that, this version of “The Koren Selihot” will certainly do that.

Ben Rothke lives in New Jersey and works in the information security field. He reviews books on religion, technology and science. @benrothke