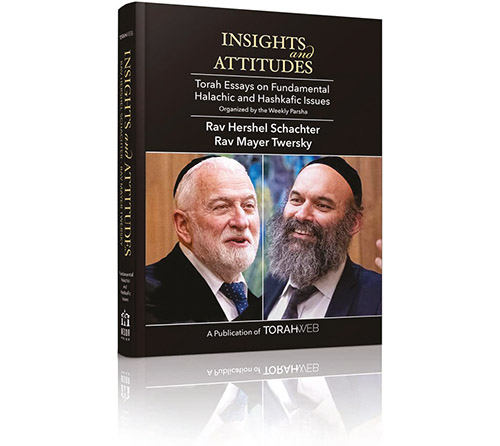

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles, organized by parsha, by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

Towards the end of Parashas Ki Sisa, Moshe is told by HaKadosh Baruch Hu that He will be giving him a two-part Torah – part bichsav, in writing, and part be’al peh, oral (see Shemos 34:27 and Gittin 60a). These two parts of the Torah must be transmitted from generation to generation, each in its own fashion. The Torah Shebichsav must be taught mitoch hakesav, reading from a written scroll, whereas the Torah Shebe’al Peh must be transmitted orally. The Talmud (Temura 14b) records that at a certain point in history, the Rabbis felt that there was a serious concern that the insistence on observing this point of law could possibly cause much of the Oral Torah to be forgotten, so they permitted the transmitting of the Torah Shebe’al Peh from a written text. The expression used by the Talmud in this context is,

מוטב תיעקר תורה, ואל תשתכח תורה מישראל — “it is preferred that one letter of the Torah be violated, rather than have the entire Torah forgotten.”

Rambam (Hilchos Mamrim 2:4) gives an analogy from medicine to understand this point: Sometimes a doctor will amputate the arm or leg of a patient in order to keep him alive. Rambam, however, quotes from the Talmud (Yevamos 90b) that such a special “hetter” may be practiced only as a hora’as sha’ah (on a temporary basis) and not ledoros (permanently).

Many centuries have passed, and the Oral Torah is still being taught from written texts of Mishnayos, Talmud and Shulchan Aruch. This poses an obvious problem. Can a practice which has continued for close to two thousand years be considered a hora’as sha’ah because at some time in the future (i.e., leyemos haMashiach) that practice will be discontinued? This issue is dealt with in the classical halachic literature.

Exactly when this change in the style of teaching the Torah Shebe’al Peh occurred was a question among the scholars. It is generally assumed today that this change occurred after the times of Ravina and Rav Ashi. The Talmud quotes several passages from the “Sefer of Adam Harishon,” the book that God showed Adam about the transmission and development of the Torah throughout the ages. One such line reads that, “Ravina and Rav Ashi will be the end of the period of hora’ah” (Bava Metzia 86a). Rav Moshe Soloveitchik took this to be referring to the aforementioned issue: because after their time the Torah Shebe’al Peh was no longer being transmitted orally, the status of the rabbis as ba’alei hora’ah was lowered in the eyes of Halacha. All the rabbis from the days of Yehoshua until the days of Ravina and Rav Ashi had a higher-level status, ba’alei hora’ah, than those that followed them. We therefore assume that while in each generation the rabbis are entitled to express their own original opinions, even in disagreement with those who preceded them, those following Ravina and Rav Ashi do not have the authority to disagree with the accepted positions of the Talmud. Only a ba’al hora’ah is entitled to an opinion (hora’ah being a definitive position on a matter of Torah Shebe’al Peh), and the ba’alei hora’ah of the later period, when the Oral Torah was no longer being transmitted orally, are on a halachically lower level.

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.