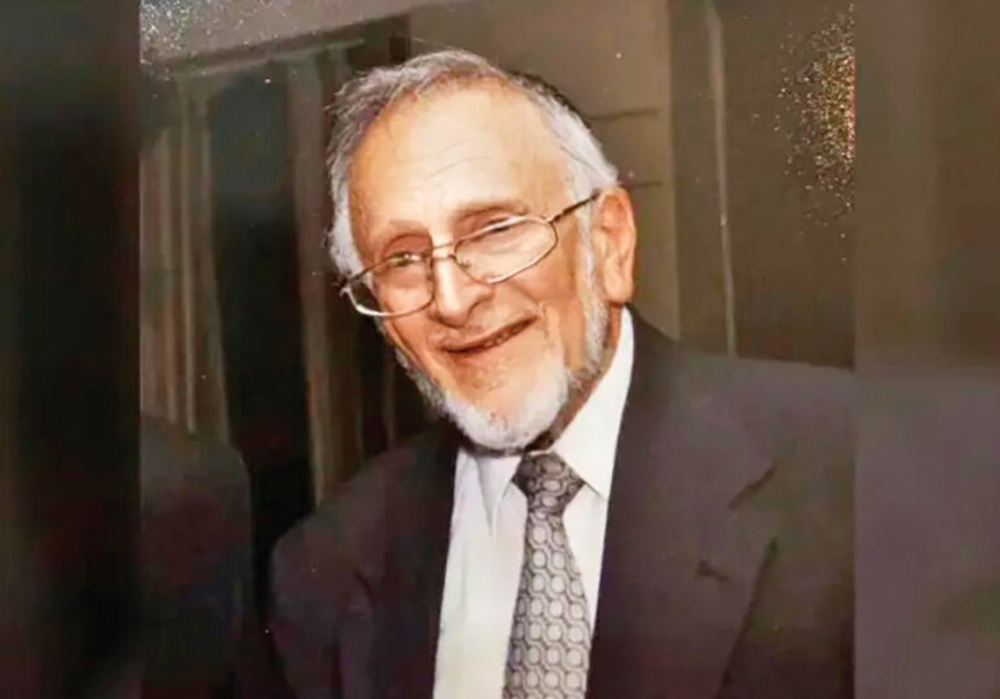

It had been an emotional Shabbos, commemorating the 10th yahrzeit of my father, Rabbi Dr. David M. Feldman, z”l. The reminiscing extended past Havdala, at which point we were confronted with a fresh wave of sad news, coming from Israel: Over Shabbos, my father had been joined in the next world by his beloved brother-in-law, Rabbi Meyer Fendel, z”l.

Knowing that these two great men would now share a yahrzeit, the 6th of Kislev, immediately brought to mind a pasuk, Shmuel I, 1:23: “Ha-ne’ehavim ve-he-ni’imi’im b’chayehem, u’v’mosam lo nifradu.” Originally a reference to Shaul and his son Yonason, who died in the same war, the text states that they were beloved and dear in life and remained connected even in death. In this case, an additional level of meaning suggested itself.

Two relatives who were beloved in life—originally brought together by their devotion to my incomparable aunt, Rebbetzin Goldie Fendel, a”h, and quickly discovered their own kindred spirits—are now reconnected by a date of death, a yahrzeit. And yet, there is another meaning still embedded in this verse that reflects on both of them.

“Ha-ne’ehavim ve-he-ni’imi’im b’chayehem”: Those who were, in their lives, the beloved and pleasant ones. So much can be understood from these words.

Rabbi Feldman and Rabbi Fendel led lives defined by scholarship and education. Rabbi Feldman was a pioneer in the field of Jewish medical ethics, author of the classic “Birth Control in Jewish Law,” which has appeared in many editions and is currently being prepared for yet another, and many other works, and a lecturer worldwide. Rabbi Fendel was a groundbreaking leader in the world of chinuch; the founder of HANC (Hebrew Academy of Nassau County), the first Jewish school in what is now the massive Torah stronghold of Long Island; and a rebbe to thousands from that school and later from institutions in Israel, and from the burgeoning community of West Hempstead, which he also founded.

And yet, in both cases, to focus on intellectual accomplishment is to miss the mark. Both rabbis accomplished what they did because they were extraordinary paragons of ahava and ne’imus, of love and pleasantness.

Rabbi Fendel identified the theme of love of people as fundamental to his educational objectives. Regarding the mission statement for HANC, he wrote, “The underlying motif is ahava, love. To this end, the educational program must be geared to a basic appreciation of the varying intellectual, social and religious backgrounds that play important roles in the child’s development. An individualized and personalized approach must therefore be used in the total development of the student.”

A student of Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim, Rabbi Fendel was always devoted to education and outreach. Only later on, however, did he discover his primary influence, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, z”l, whose teachings would profoundly influence his worldview and never be absent from his own divrei Torah. Leafing through a book in a bookstore, around the same time he was planning the vision for HANC, his attention was “completely caught” by the quote that “the truly righteous do not complain about evil, but rather add justice … they do not complain about ignorance, rather add wisdom.” This led him to wonder, “Who was this Rabbi Kook, the author of this remarkable statement that seemed to embody so much of what we were trying to accomplish and teach in HANC?”

Torah returns to its host: He had married the daughter of my grandfather, Rabbi Moses J. Feldman, who had been a student of Rav Kook’s in London, later writing a biographical sketch of him (eventually published in five parts in the Jewish Press) “due to the profound effect” he had on him. Rav Kook’s philosophy of love for all Jews would come to similarly profoundly affect Rabbi Fendel and resonate with his instincts.

Rabbi Fendel summarized Rav Kook’s educational philosophy by writing, “Real chinuch means gently and positively guiding the child, with ‘ways of pleasantness,’ to the self-realization and insight that the path of Torah is the best way—certainly ‘better’ than what he had before.”

As a young child, I would frequently travel to West Hempstead to spend Shabbos with my aunt and uncle and cousins. What I would witness there amazed me: such an unusual model for a high school principal! Students would constantly be over at the house, seeking to spend even more time with him, in informal contexts. The effect Rabbi Fendel had on his students was palpable, and those Shabbos gatherings are a frequent subject of their testimonies decades later.

Rabbi Fendel hired many great Torah scholars to teach at HANC, but one I knew personally was Rabbi Shlomo Wahrman, z”l. Rabbi Wahrman was a towering Torah giant who authored sefarim of genuine stature, yet made it his life’s mission to teach high school students, and prioritized love of people in his halachic rulings in ways that were impossible to miss and sometimes extraordinary. It is little wonder that Rabbi Fendel appreciated him; he would write forewords to Rabbi Wahrman’s books, highlighting his qualities of “pleasantness and sterling character, teaching Torah to all of his generation.”

These qualities of Rabbi Fendel were central in allowing my uncle to bond so closely to my father. They shared many loves: a love of Torah, of teaching, and of the Jewish people, of people in general. Despite my father’s devotion to scholarship and writing, he chose to make his career not in academia but in the pulpit rabbinate, approximately 20 years each in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn and in the Jewish Center of Teaneck. In a “Rabbi of the Year” acceptance speech (available on YouTube) that I turn to whenever I need support and inspiration, he explains his rabbinate through the prism of love for people.

At the shiva for our father, Rabbi Dr. Moshe Tendler, z”l, offered his theory as to why Rabbi Feldman, who had not trained as a doctor, chose to enter the field of medical ethics, positing that it was driven by his need to find ways to help people. “The big techunas hanefesh (personal quality) of his was he was very zahir (careful) in his midos (personal attributes), you could see he was really interested in helping people in trouble, not an easy task to undertake.” He went on to explain the cryptic statement of the Mishna that places “the best of doctors” in Gehinom (Kiddushin 82a); a superior doctor is able to empathize with his patients and feel their suffering; he is with them “in Gehinom.”

For our father’s funeral, Rabbi Fendel, who was unable to travel from Israel, sent a letter to be read, which from its opening words identified their shared values. “Ahava, love. Our Davie was the epitome of love: love for everyone he encountered, for his congregants all over and especially for his family, his children, father, brothers and sisters, and especially his dear wife, Aviva, his lifelong loyal helpmate. As Goldie, his sister, often said, he was a real tzaddik in his relationships with people, bein adam l’chavero, in every sense of the word. … He was a pillar for our family. He was always called upon for his advice in every manner. He actively cared for and supported others, bringing out goodness and happiness in everyone around him. He was blessed with a sweet and good disposition, always ready with a special smile, mixed with wise words. He helped so many people in times of need, helped them face life’s challenges … with humor and strength. … How we will miss his wonderful sense of humor, his beautiful way of listening, his wonderful smile, the love…. As a congregational rabbi, was he beloved by the two large communities he served…”. After adding words of great praise regarding our father’s scholarship, he concluded his letter by noting the Talmudic application (Gittin 36b) of a verse (Shoftim 5:31) he claimed must have been “written exclusively for our” Rabbi Feldman: “v’ohavav k’tzeis hashemesh b’gvuraso, Let those who love Him be as the sun in its might,” that blesses those who can maintain a kind and forgiving attitude to all.

In his rabbinic award acceptance speech, my father made reference to Rav Kook, citing the idea that if the Talmud blames the exile on sinas chinam, causeless hatred, then the remedy must be ahavas chinam, a love that needs no reason or justification. A beautiful thought, indeed; however, my father noted, the notion predates Rav Kook. It can be found in the words of the prophet Hoshea (14:5), “Ohavem nedavah, I will love them freely.”

As Providence had it, those words were read publicly in the Haftorah 10 years ago, less than one day after my father passed away. They were read again this past Shabbos, on my father’s 10th yahrzeit and on the day my uncle passed away. The legacy of Rabbi Fendel’s and Rabbi Feldman’s lives couldn’t ask for a better expression.

Rabbi Daniel Feldman is the rabbi at Ohr Saadya of Teaneck; a rosh yeshiva at RIETS and sgan rosh kollel of the Bella and Harry Wexner Kollel Elyon; as well as an instructor at Syms School of Business.