Reviewing: “The Book of Torah Timelines, Charts and Maps” by Rabbi Avrohom Biderman. ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications. 2024. 115 pages. ISBN 13: 978-1-4226-4064-7 (English Hardcover), 4065-4 (English Paperback), 4066-1 (Hebrew Hardcover) 4067-8 (Hebrew Paperback).

Many who study the Talmud are familiar with “פירוש חי,” a series that contains hand-drawn diagrams of some of the concepts and items discussed in certain masechtos. Over 40 years ago, I bought a set of Eshkol Chumashim in Israel that has illustrations in the back of each volume, which help explain some of the things mentioned in the Torah. Other publishers have done the same, and when ArtScroll published Chumashim for grade-school students—Chumash Tiferes Michael—they added many helpful features in the back of each volume, including extensive color illustrations and charts that concretize many abstract or complex ideas contained in Chumash. These illustrations and charts were then adapted for adults and included in the back of the Czuker Mikraos Gedolos. They have updated them again, published in a single volume, “The Book of Torah Timelines, Charts and Maps,” (“מפות, טבלאות וסדרי המאורעות שבתורה”).

Differing opinions can make it difficult to graphically represent what פסוקים are trying to convey. Nevertheless, ArtScroll sidesteps this issue by (mostly) limiting their portrayal to how Rashi explains things, which works well for young students. Even when updated for adults, a disclaimer that Rashi’s opinion is being followed provides adult students with a starting point; advanced students can try to visualize the nuances that arise as they encounter other opinions.

There are two main differences between the earlier editions and this one: (1) Until now, the text was all Hebrew (as it continues to be in the Hebrew edition of this new volume); The English edition not only also identifies everything in English, but presents the included information in English as well. (It should be noted that even though the page numbers of the Hebrew and English editions match exactly, the illustrations are not always an exact match; when they aren’t, I found the ones in the English edition to be more precise.) (2) Rather than being presented in the same order as the Torah, the new volume is divided into categories: Timelines, Charts, Maps, Illustrations, the Mishkan and the Kohanim’s Garments and the Korbanos/Offerings. Being divided by category rather than subject causes some related items to be in different sections rather than on the same page or in the same section. Additionally, although the table of contents can help locate something as you study Chumash, because it’s not in the order of the Chumash, it can be difficult to know whether there’s a chart or illustration for what you are learning. An index by parsha (or chapter/verse) would be extremely helpful.

Many of the updates are the result of the pages being slightly wider—allowing some of the graphics to be easier to see—as well as having the ability to include more information on each page or to rotate a chart in a way that’s easier on the eyes. A number of updates from Chumash Tiferes Michael are similar to those in the Czuker Mikraos Gedolos, primarily because being geared towards adults makes some of the pictures and illustrations superfluous (e.g., not including a picture of each animal again for every korban), and the condensed information allows what was on multiple pages to be combined into a single page. Generally speaking, the headers are much better in the new volume, and there have been some significant updates from both earlier editions—such as the order of how the לחם הפנים was made (the flour was divided into 12 parts rather than dividing the dough into 12 parts) and the boundaries of the 12 Tribes (e.g. a strip of Gad now reaches the Kinneret and the southern part of the eastern end of Binyamin no longer abuts the Dead Sea).

The section on korbanos is very helpful when trying to keep track of and understand their details. The illustrations of the Mishkan are excerpted from ArtScroll’s Kleinman Edition of “The Mishkan—Its Structure and Sacred Vessels,” and for those who don’t have that (or a similarly extensive “Mishkan” book), this section alone makes this volume worthwhile (even if I disagree with their approach to the courtyard pillars). I would have included more illustrations from the Shemos volumes, and in all three editions, I would have included the Shulchan with the upper rods that supported the לחם הפנים in this section too—not just in the section of korbanos.

The timelines provide a great overview of numerous biblical events (e.g., the flood, the Exodus, the giving of the Torah, the building of the Mishkan and the 40 years in the desert); the graphical representation of the lifespans from Adam to Yaakov shows whose lives overlapped with whom (e.g. Noach and Avraham, and Shem and Ever with the Avos), although Shelach and Ever’s graphs need to be corrected. (The information is correct, and their graphs were correct in the Bereishis volumes.) I received a well-written form letter when I emailed ArtScroll about it; based on their correction to the making of the לחם הפנים, I am confident this will be corrected too.

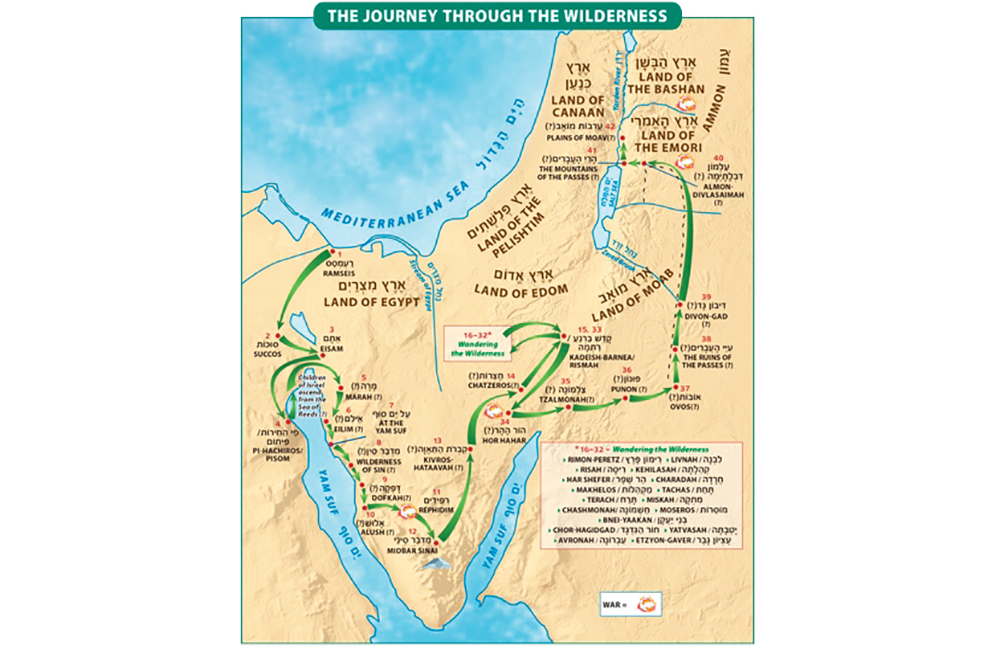

The lower basin of the Dead Sea is presented as having formed when Sodom was destroyed (another conclusion I disagree with). The most interesting update to the maps is the addition of a green arrow indicating where the children of Israel crossed the Red Sea. Although it’s already obvious in the previous versions that they are following the commentators who say we came out on the same side we entered (since the arrows lead to and from the sea on the same side), they added one in the sea itself. I discussed the issues that led to this conclusion at length; from the provided map you can see why there is no need to say we came out on the same side (e.g., how we could have been at Eisam both before and after crossing from one side to the other), but I understand why ArtScroll presents it the way so many commentators do. Because they are presenting Rashi’s opinion, Har Hahar is put south of Edom rather than west of it. There aren’t any notes explaining why Kadeish-Barneya is in a different location on the map of the southern border of Eretz Yisroel than on other maps. They also leave out Kadeish—which avoids some major issues—but makes the map of the 42 מסעות somewhat incomplete. Nevertheless, you certainly get a better sense of what the Chumash is referring to by referring to these maps.

Despite the overlap between the three editions of these charts and illustrations, the new volume has some welcome upgrades. It could be argued that they should have included more already-existing material (and that they included some material unnecessary for adults), but this one volume costs far less than even a single volume of one of the Chumashim, making it a worthwhile addition to your bookshelf.

Rabbi Dov Kramer wrote about geographical issues as they relate to Chumash in 5784, available at JewishLink.news/author/Rabbi-Dov-Kramer and at dmkjewishgeography.wordpress.com. He discussed the location of Sodom for Vayeira , the crossing of the Red Sea for Beshalach, the courtyard pillars for Terumah and Tetzaveh, Kadeish Barneya for Shelach, Rashi’s opinion on where Kadesh and Har HaHar are for Chukas and more about Kadesh for Devarim.