In the 1980s and 1990s, the Young Israel of Woodmere experienced tremendous growth, regularly attracting more than 700 people to the main services in the sanctuary. But to outsiders it was known as the “talking shul,” as the services always had excessive conversations going on among congregants throughout the tefillah.

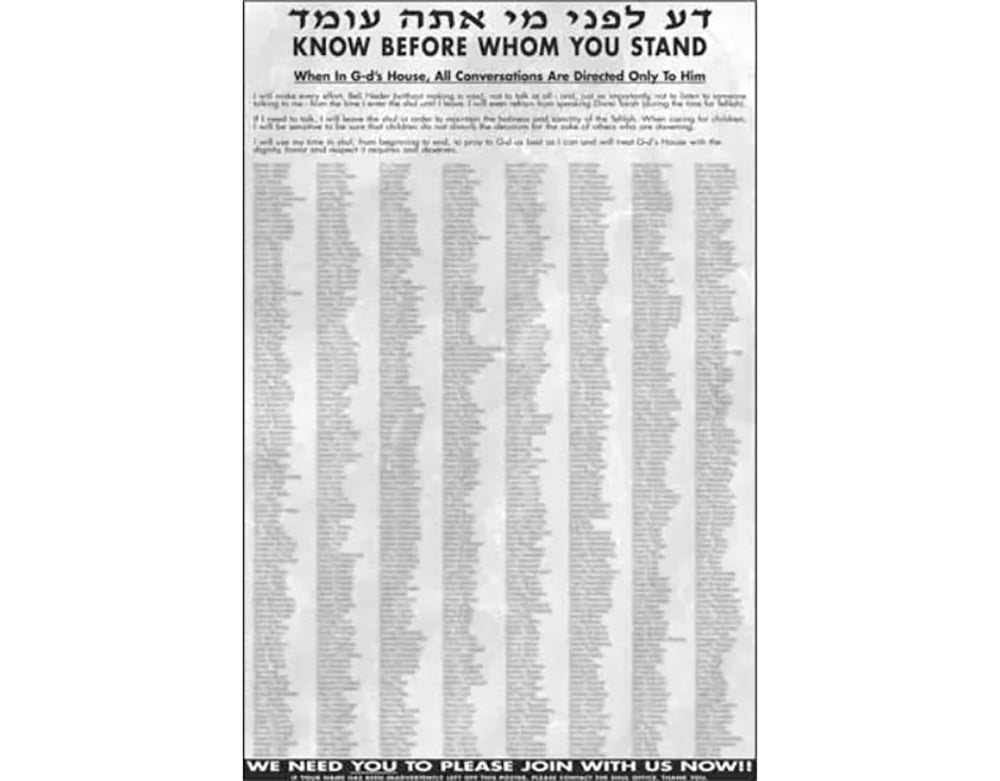

Twenty years ago, that dramatically changed, in no small part due to a creative campaign. The shul asked all its members to voluntarily sign “A Commitment to Tefillah and Proper Decorum.” They sent this request to every shul member on four occasions. Over time, more than 1,000 members signed the agreement. The list of signatories, which was posted prominently in the shul lobby, publicly recognized those who made a commitment to maintain shul decorum, while also serving as an ongoing reminder that the shul felt a quiet service was important.

Did the campaign work? Incredibly well! In fact, visitors who had not been to the shul for some time told residents that they thought they were in the wrong shul, so baffled were they by the change that had transpired.

I spoke to Rabbi Heshie and Rebbetzin Rookie Billet, who were instrumental in creating the campaign, about their recollections. They were happy to share their thoughts on the subject.

Who came up with the idea of members signing a petition not to talk during tefillah services?

HB: I do not recall exactly. It came out of a meeting of people who were concerned about having decorum in the synagogue.

RB: It was not really a petition, it was making a commitment and signing on to that commitment. My recollection is that Heshie and I came up with it, but I cannot be sure. Personally, I’ve always been a big believer in making a resolution and sticking to it. A large poster was printed with all the people who made the commitment, and we displayed it in the lobby.

How were you able to sell it effectively to shul members and get so many people to sign it?

HB: I think that it did not have to be sold. Most people, if asked, know that there is a standard that should be upheld in the synagogue. Most people do not make noise in the synagogue. But there is a significant minority that does.

RB: I recall that in the context of selling it, there were a couple of sermons dedicated to the concept of the importance of meaningful prayer, what a decorous synagogue says about a community. Also pointed out were these ideas: 1) How, since we are all affected by the human condition, we should pray for others as well as ourselves. 2) The fate and destiny of the Jewish people is dependent on our building a relationship with God. We see value in that relationship, and we must demonstrate to ourselves and to our fellow community members that this is something we care about. Finally, there was a committee of people who were committed to the idea. They made phone calls urging people to sign on.

Why do you think so many Orthodox shul-goers talk during the services, when they all know down deep that it is wrong?

HB: There could be many reasons, but I think the main reasons are that the services are too long and congregants do not understand what they are saying.

RB: I think that conversation at synagogue is about seeing the synagogue as a center of Jewish life in the community. People are very busy all week with family and work obligations and don’t have time to socialize. At synagogue, we see friends that we enjoy and converse with them. The word “beit Knesset” actually means “a place where people gather.” People also do not know the laws of hefsek during services. Even when they do, people who talk during services do not think it’s a big “sin.”

Besides a petition, what else can other shuls do to prevent talking in shul during services?

HB: If I had any really good solution, I would tell you. Education is important. The rabbi must speak about it. There needs to be a significant number of lay people committed to the idea.

RB: I think we felt that it was important to try to make decorum in shul the “in thing.” Making sure the services went quickly without delay was an essential part of the campaign. Prior to the campaign, there was a lot of waiting time for decorum. For example, the Torah reading portions would not begin until it was quiet. That added many minutes to the length of the services. A great effort was also made to make sure that those who lead the services would make them well-paced and no-nonsense, but also melodious and user-friendly.

We also placed the sermon after Adon Olam so that anyone who did not wish to attend could leave—and only those who wished to be there would stay. Interestingly, my observation from the balcony was that very few people left. But the fact that the option was there helped.

In sum, cutting down on waiting for quiet, putting the sermon at the end, making sure those who lead the services were committed to keeping it short helped dramatically. Anim Zemirot was sung before Mizmor Shiur instead of after Mussaf. This also saved five to seven minutes at the end of the services, which was the noisiest time. Using these measures, perhaps a half hour was cut off the services, ending them at 11-11:15 a.m. instead of closer to noon.

Before 2005, how did you handle the problem of talking in shul during services? Did you stop services at certain points when talking became too loud? Did you make announcements not to talk? Did you have any educational program about the halachot relating to speaking at certain points of the service?

HB: We did all of the above. I used to come down from the pulpit during Torah reading and walk to the talking areas. I did the same during the repetition of the Amidah. When I was in the area, people quieted down. But as soon as I moved away from their sections, they resumed their conversations. I can compare it to a pitcher in a baseball game trying to check the runner at first base. When he looks over there, the runner runs back to the base. When he looks away, the runner takes a lead and sometimes tries to steal second base. Most rabbis would not do what I did. There are also well-meaning lay people who see it as being beneath the dignity of the rabbi to do such a thing.

RB: As mentioned above, yes, we stopped the services all the time to wait for quiet. And yes, polite requests for quiet were repeatedly made from the pulpit.

Why do you think nothing worked effectively until you came up with the petition idea?

HB: I cannot say that the petition was totally effective. I guess, to some degree, people have integrity. If they sign something, most people try to live up to their commitments. But I cannot say that the petition made a huge difference in the long run. In the short run, the decorum efforts work. But over time people just forget about the commitments they made.

RB: I think it wasn’t only signing the commitment that helped, but all the above in combination.

What are some of the measures shuls can do to streamline and shorten the service, which some feel contributes to the problem of talking (service is too long)?

HB: I think if some of the authorities that our community looks up to would take some courageous positions, they could shorten the services by at least half an hour. To elaborate, Pesukei D’zimrah can be dramatically shortened. Perhaps the Amidah does not have to be repeated. That is often done during the week when we are in a rush at Mincha time. We call it “heicha kedusha,” Perhaps that could be done for Shacharit and Mussaf.

To accomplish this, the YU roshei yeshiva would have to give license. It would be criticized, and it takes a lot of guts to do this. But shortening the service would go a long way to improving the decorum. In our synagogue, the rabbi’s sermon was pushed off till after the end of services. Anyone who wanted to leave could leave. That automatically shortened the actual davening portion of the services by anywhere between 10 and 20 minutes.

RB: I addressed this above, and all those measures helped. Even when the sermon was before Mussaf, that portion of the services was respectful because human nature tends to make us respect individual people, but it may be harder to respect a concept like decorum which is so abstract. The psychological effect of having the sermon at the end, therefore making it only optional, was a demonstration of genuine commitment on the part of the rabbi, which also helped.

Living in Israel these last few years, we have observed that shuls here do not have decorum problems. Perhaps that is because people here are living under a constant existential threat. Perhaps it is because the language of the siddur is the native language of the people. These considerations lead us to suggest that American Jewry should take strong measures to improve their Hebrew and also feel more powerfully the existential threat to our people, not only in times of crisis.

What did you do about incessant talkers after the program began? Did you try to speak to them privately?

HB: We tried. I probably did not do enough about private conversations with people.

RB: I recall that committee members made appointments, and people were spoken to privately. It’s important to note that we have many parallel minyanim on a Shabbat morning. Many of these were already quiet and perhaps they were founded in order to be quiet, so it was mostly the main sanctuary that needed all of this effort

Were you surprised how well the campaign worked? Were the congregants surprised?

HB: It worked within limitations. We did not do a survey of the congregation.

RB: I think that there were a fair number of truly committed people who really wanted this to happen. I would particularly cite our executive director, Rabbi Danny Frankel, who was deeply committed to the concept and worked very hard to implement the program. He had previously led the high school/college minyan, which had been a wonderful minyan for the youth.

Michael Feldstein, who lives in Stamford, is the author of “Meet Me in the Middle” (meet-me-in-the-middle-book.com), a collection of essays on contemporary Jewish life. He can be reached at michaelgfeldstein@gmail.com.