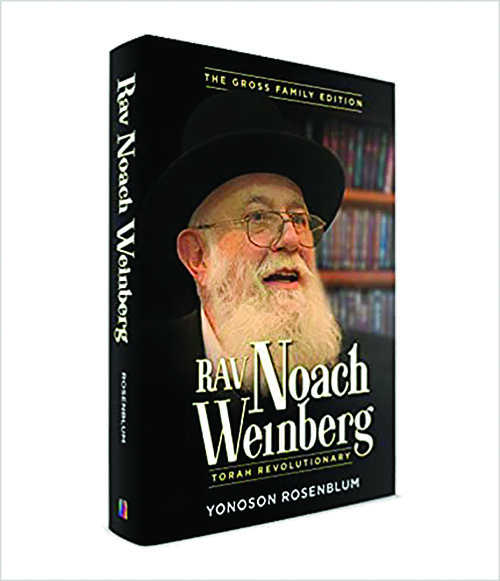

Reviewing: “Rav Noach Weinberg: Torah Revolutionary,” by Yonasson Rosenblum. Mosaica Press. 2020. English. Hardcover. 454 pages. ISBN-13: 978-1946351876.

Two sentences into the long-awaited biography “Rav Noach Weinberg: Torah Revolutionary” by Yonason Rosenblum and I was ready to close the book. He opens with a template story straight out of a hagiography. Thankfully I kept reading and was a better person for it. Aside from but a single additional page of hagiography, Rosenblum has written a remarkably insightful and candid memoir about one of the most important Jewish figures of the last 50 years.

While Rav Noach was one of the earliest founders of the kiruv movement, one must understand the milieu in which he grew up. He was thinking about kiruv in the early 1950s. This was just after World Word II when the notion of bringing Jews back to Orthodoxy was an utter absurdity. His label then as “Noach, the meshuggener” was certainly a pejorative, but at the time, accurate. Conservative and Reform Judaism were at their apex, and the future of Orthodoxy was in doubt. This chronicle shows how remarkably prescient Rav Noach was.

There is the well-known story of Rav Elya Meir Bloch of the Telz Yeshiva, who went into a sefarim store in the Lower East Side in the early 1950s and asked to purchase a copy of “Ketzos Hachoshen.” The owner gave it to him and told him that it was the last “Ketzos” that would ever be sold in the United States. The owner was simply echoing the reality of the times. Any rational, i.e., non-visionary, person would have thought the same. Rav Bloch, like Rav Noach, were visionaries. Rav Bloch was about Torah flourishing in America, and Rav Noach was about bringing the Jewish people back. Had either of them gone with the times, the world today would be a much darker place.

As Rosenblum eloquently writes, Rav Noach was not some wild-eyed dreamer; rather, he had a laser-focused understanding of the problems facing the Jewish people. An important point he shows is that Rav Noach was not a one-trick pony with kiruv. His laser-focused vision was apparent early on, long before the phenomenon in the Torah observant world of “adults at risk” was ever a topic. Rav Noach warned that the lack of emphasis in the Torah educational system on the necessary foundations of Judaism would undermine the Torah world from within. The outgrowth of that was Project Chazon headed by Rabbi Daniel Mechanic.

Rav Noach could have thrown in the towel after his myriad setbacks and betrayals. Furthermore, his surrender would have been fully justified. However, Rosenblum details in chapter after chapter, Rav Noach knew that he was not working for himself, instead for the Almighty and his children, and felt he did not have the right to surrender.

Rosenblum has written a remarkably candid biography that details the many successes and failures that Rav Noach faced. The title correctly calls him a revolutionary. Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein noted that the Torah prefers evolution, rather than revolution. Nonetheless, be it the Baal Shem Tov, Sara Schenirer or Rav Noach, these revolutionaries knew that taking revolutionary responsibility for the Jewish people meant incurring the wrath of many of those who preferred the status quo, and the approach of sha shtil, makh nit keyn gerider (be passive and do not make noise).

This is the only biography I have ever read where I knew the subject intimately well. Having spent over four years at Aish, the book was a walk down memory lane. While Rosenblum has done an extraordinary job, I am reminded of the events of chapter three from the book of Ezra. It says that “When the builders had laid the foundation of the Temple of the Lord, priests in their vestments with trumpets and Levites, sons of Asaph, with cymbals were stationed to give praise to the Lord, as King David of Israel had ordained.” However, a few verses later, Ezra writes, “many of the priests and Levites and the chiefs of the clans, the old men who had seen the first house, wept loudly at the sight of the founding of this house.”

To those who knew Rav Noach, walked with him and spent extended periods with him, the book does not capture the essence of who he was. It does not capture his passion, his exasperations, his sense of urgency and who he really was. This is undoubtedly not Rosenblum’s fault, as the written word simply lacks that capability to detail such a unique personality fully. Words cannot capture the essence of the person such that you can truly understand them from a biography. That may be why the oral Torah was originally forbidden to be written down—because the nature of it simply cannot be put into words. Furthermore, when it is put into words, it loses much of its essence.

For example, when reading of Rav Noach’s habit of snapping his fingers, it could sound like an odd, almost Tourette-like habit. However, those who walked through the Old City streets with Rav Noach will understand precisely what that snapping meant. Rather than being odd, it was his method to raise his consciousness to be aware of God and was a mechanism to focus and remember the six constant mitzvos.

If Rav Soloveitchik was “the lonely man of faith,” then Rav Noach was “the lonely man of kiruv.” His was a struggle he faced in large part alone—away from his family for a large part of the year on fundraising trips, and alone in his struggle to bring back the Jewish people to their roots. Rosenblum does not hold back and writes of the countless antagonists and naysayers that got in his way.

In the world of biographies written by and for the Orthodox world, this work is unique in its text and approach. Rosenblum does not sugarcoat things, and where Rav Noach’s imperfection needs to be discussed, he details them. His research was superb, and the accuracy of the book is due in large part to the assistance of Rabbi Asher Resnick, a long-time and close student of Rav Noach.

The only error I found was Rosenblum’s statement that Rabbi Amram Blau of the Neturei Karta was fluent in English, both spoken and written. According to Motti Inbari, professor of religion at the University of North Carolina and author of “The Making of Modern Jewish Identity: Ideological Change and Religious Conversion,” which has a chapter about Blau—Blau certainly did not know how to read English. However, Inbari speculates that he may have known how to speak English because of his connections with the British Mandate and the British government. Inbari notes that Blau prohibited his wife from publishing in English because he could not read her papers to review the text for accuracy.

There is nothing not to like in this remarkable and inspirational biography. If I have any complaint, it is that I would have loved it to go on for another few hundred pages. But at 550 pages, the book is certainly thorough and engrossing.

One is hard-pressed not to find a Jewish community worldwide that has not been a beneficiary of Rav Noach’s wisdom and efforts. Rosenblum has done a superb job in finally bringing the magnificent story of Rav Noach Weinberg to print.

By Ben Rothke