Jake Rabinowitz spent his junior year of college (1969-1970) as a student abroad at the Hebrew University campus located in Givat Ram in west Jerusalem. As an undergraduate transfer student from Columbia College in New York City with a sufficient command of the Hebrew language, he had registered in August 1969 for 10 varied courses from the regular Israeli catalog. The school year was divided in those days into three trimesters with exams being given only upon the completion of the lecture schedule in July 1970. The lengthy school year was broken up by sizable breaks in the schedule: The months of October, January and April were free from classes.

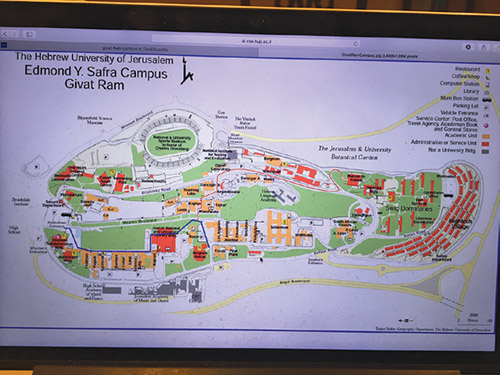

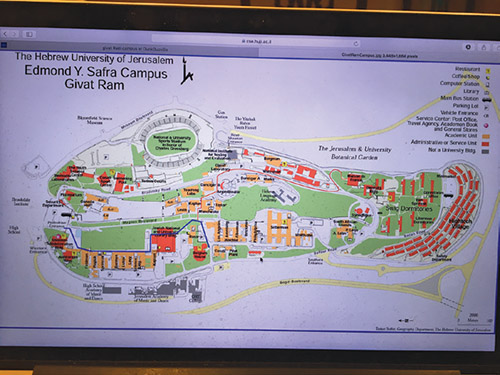

Since Jake was familiar with Jerusalem, having spent almost two months living there in previous summers, he opted to live off campus during the school year in the Kiryat Shmuel neighborhood, where he rented a room on Rechov Ha’ari off of busy Aza Street. Daily he would board either the #15 or #9 bus around the corner from his home and travel the 15 minutes to the campus gates to attend classes. The campus consisted of a dozen or so large, modern buildings, named for early Zionistic leaders and educators, containing auditoria, mathematics, science and social science classrooms, along with offices for teachers. The southern part of the campus contained dormitories, and the area between the dorms and the academic buildings was a beehive of construction activity as the campus was undergoing major improvements as the academic year unfolded. This was the time in Jerusalem’s recent history when the campus of the Hebrew University on Mt. Scopus was only recently restored to Israeli rule with the conclusion of the Six Day War. Accordingly, the Givat Ram campus in the west was at this time effectively the Hebrew University for all practical purposes.

Jake found his transition to studies and lectures in the Hebrew language not too difficult, and after several weeks he established a routine of attending classes, hiking to an inexpensive lunch at one of several on-campus cafeterias and socializing with friends on the campus greens. Jake had made the trip abroad with several of his college classmates, maybe numbering a half dozen or so. Like most of his American friends, Jake made few Israeli acquaintances at school, in part because of the language barrier, but mostly because of the age differences between the foreigners and the Israelis. The latter mostly entered the university at the conclusion of their mandatory military service at 22 or 23, while the average American was three to four years younger.

The classes at the university were rigorous, and Jake and his friends sought recreation wherever and whenever they could find it. There were no organized exercise classes or sports activities, with movies in downtown Jerusalem providing most of the amusement, particularly on Saturday nights, when there were two showings after the Sabbath ended. Despite being 6,000 miles from home, Jake regularly got to view first-run U.S. films in theaters such as the Zion, Orna and Orgil in central Jerusalem.

The lack of organized sports activities, as mentioned, did not prevent the Americans from spontaneously participating in various pickup games on campus. During a lunch break, for example, a friendly soccer game would take place between mixed American and Israeli sides. At other times an American touch football game might break out with Israelis watching bemusedly from the sidelines as the American “quarterback” attempted a 30-yard pass with that strangely shaped American football, that just as often as not ended up striking some unsuspecting Israeli coed as she hurried along the path to her next class, knocking her books flying. No one kept score at these games and they were essentially played for the sheer fun of stretching one’s legs and out of boredom.

On one occasion, things took a more serious turn. On this particular November afternoon, following a political science class, Jake met his friend Ben outside the building and they both asked to join a football game that was forming nearby. Each was assigned to an opposing team and the play commenced. After 10 minutes, the critical play occurred: The quarterback on Ben’s team attempted a long pass to Ben, who had beaten one defender. Jake, playing deeper, attempted to cross the field and intercept the pass. As happens on many such occasions, both Ben and Jake missed the ball, but in jumping up to attempt the reception, they collided directly, with their heads taking the brunt of the impact. Both friends fell to the ground and were soon surrounded by concerned players and some of the dozen or so Israelis who were watching the match. Ben soon recovered, but Jake was woozy for several minutes.

“Sit down on the bench over there for awhile,” suggested one of the Israelis, pointing to the nearby path. Jake followed the suggestion. After about 10 further minutes, he was not feeling much better, so he wondered if he should have his head injury evaluated by a doctor or nurse. He had a bad headache for sure, not to mention the large bump that was beginning to form on the side of his head. Ben stayed with him during this time but had a class to attend soon.

“Maybe you should go to an emergency room at one of the hospitals. Maybe Hadassah has one,” he suggested.

Ben’s advice was sound, because it turned out the Hadassah hospital emergency room was part of the university’s student health service, so Jake was covered. With some difficulty, he located the proper bus and soon alighted at the modern-looking hospital several miles away from the campus. Jake registered with the nurse at the desk, using his broken Hebrew to describe how he was injured. When she got all of his information, the nurse motioned to Jake to sit at the end of a row of six or seven patients who were waiting their turns to be seen by a doctor. After about 10 minutes, Jake began to feel restless and started stretching his lengths in a sort of rhythmic fashion, which caught the attention of a nurse who rushed over to Jake and, concerned he might be suffering a seizure of some kind, inquired about his condition.

“I’m okay,” he said, but she insisted he follow her to the head of the line to be promptly examined by the doctor.

“We’ll take an X-ray of your head just to make sure it’s nothing serious,” said the doctor to Jake following his examination, “and pending the results, I suggest we observe you overnight to make sure you’re alright.”

The X-ray proved negative, but Jake was wheeled into a large ward in which he was to stay as a “guest” of the hospital. Ward B, as it was called, consisted of 20 beds arrayed in two sections of 10 beds lining opposite walls. Jake was assigned to the last bed on one of those walls. As the wheelchair carrying him came to a halt, Jake noticed that the ward was empty except for a woman patient in a bed on the opposite side of the ward. Next to her bed sat a man (presumably her husband) looking concerned and somewhat helpless. They were silent. Jake checked his watch; it was now 5:30, and he made himself as comfortable as he could for the long night ahead. He was feeling a lot better now, and almost regretted agreeing to stay the night at the hospital, feeling he could have gone home to recuperate. But there was no one to talk to so Jake lay there daydreaming for awhile.

After an hour or so, the doors to the ward swung open and an attending physician made a stop at the bed across the room where the woman lay. He took the man aside and, after a moment or two, Jake could clearly hear sobbing. Jake surmised the prognosis wasn’t good for the man’s wife. The doctor continued down the ward toward Jake’s bed, but instead of stopping at his bed, he sat down at the end of the bed just next to Jake’s. Suddenly, as if by magic, the bed sheets and blankets on that bed, previously inert, began to slowly stir, and amidst the mountain of bed coverings emerged a rising Hebrew voice reciting crescendo-like: “Ten li ochel! (Give me something to eat!) Ten li ochel! Ten li ochel!” Jake was somewhat shaken as it became clear to him that the bed next to him, which he had thought empty, had been occupied by this previously inert individual the entire time Jake had been there.

The doctor spoke quietly but firmly to the patient, attempting to examine him as required. The man was dressed in a crumpled suit of Yemeni Israeli fashion and was clearly inebriated, which accounted for his previously stupefied state. The doctor assisted him to an upright position, which the man could only sustain with the doctor’s assistance; as soon as the doctor turned to grab his blood pressure machine, the man fell back onto the bed. The doctor raised him again and again, but each time the patient failed to stay up. Jake didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. The Yemeni maintained a steady cry for food, until at last the doctor addressed that issue by telling him he would order food for him in several minutes if only he sat still.

At this point, Jake felt completely normal and the idea of spending the rest of the night side by side with his still somewhat inebriated neighbor tilted the balance in favor of a quick exit.

“Doctor, you know I’m feeling a lot better and I think I’d like to continue my recovery at home. Please discharge me now. I’ll sign whatever releases you require.” The doctor complied, and in about an hour, Jake was in his room in Kiryat Shmuel, somewhat sore, but glad to be by himself.

Joseph Rotenberg, a frequent contributor to The Jewish Link, has resided in Teaneck for over 45 years with his wife, Barbara. His first collection of short stories and essays, entitled “Timeless Travels: Tales of Mystery, Intrigue, Humor and Enchantment,” was published in 2018 by Gefen Books and is available online at Amazon.com. He is currently working on a follow-up volume of stories and essays.