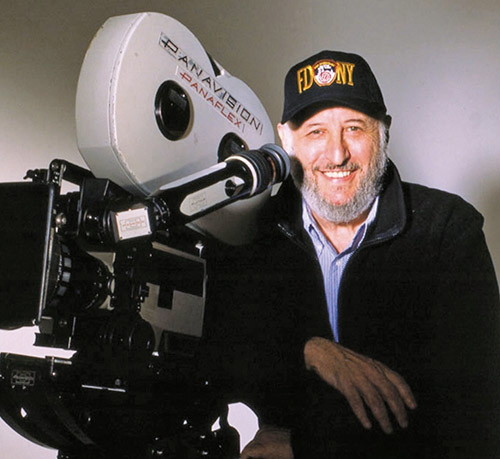

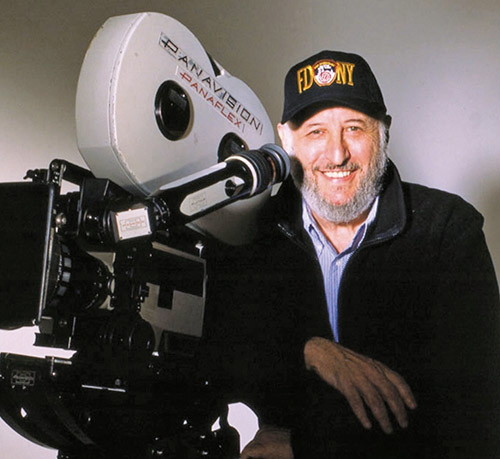

Rabbi Berel Wein, executive producer, and Ashley Lazarus, director and writer, have released another groundbreaking film. “Abarbanel—A Man of Many Worlds” is about the enigmatic Torah commentator who lived from 1437-1508. The film was co-written by Jesse Cogan.

Rabbi Wein is known for his articles, books, educational films and audio recordings on Torah and Jewish history. Previous films included “Rashi: A Light After the Dark Ages” and “Rambam: The Story of Maimonides,” also created together with Lazarus. The late Leonard Nimoy played the voices of both Rashi and Rambam, and the film on Rashi was narrated by the late British actor Paul Scofield. These films are seen in more than 1,000 Jewish schools, of every denomination.

The creators of the meticulously researched Abarbanel film say they did it within a much tighter budget than previously; nevertheless, the film’s visuals and music are breathtaking and the excellent narrator and voice actors, who dialogue as the historical characters, keep viewers engaged and intrigued.

At the world premiere held in Jerusalem, Rabbi Wein said: “The Jewish people are built of heroes but we don’t know anything about the people… The Rambam lived in a Moslem society and Rashi in a Christian society… We [might] think that Rashi had no responsibilities and that Rambam sat under the protection of the sultan. But if you study their lives, it’s miraculous that they produced anything. The Torah is multifaceted. Rashi and Rambam are not alike, but they are the pillars upon which the Jewish world rests.

“I wanted to make a third film [in this genre], about someone who could not be put in a box—the Abarbanel. He was a Torah scholar, a philosopher, knowledgeable in science and medicine, financial adviser to kings and empires. He lived in most turbulent times…”

The Abarbanel was a leader of Spanish Jewry at the time of the Inquisition and the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. “He was a hero, even in his defeat,” said Rabbi Wein. “He couldn’t reverse the exile but his heroism was in not taking the easy way out… He was one of the most exemplary figures in Jewish history.”

Lazarus also spoke before the screening.

“First of all, thank you to Hakadosh Baruch Hu,” he said. “This is a miracle.

“When I told a baal tzedaka [donor], the late Leon Scragowitz [said] of the challenges in making Jewish films, ‘We have a Jewish historian—Rabbi Wein; we have a filmmaker—you, Ashley, and me? I write checks… Where is your emunah [faith]?” There is an Abarbanel Family Association of approximately 3,000 descendants of the commentator, and some of them were also among the 22 donors who helped financially to create the film.

Lazarus said that, to make the film affordable, “We sourced classic paintings from museums and art galleries around the world. We used photographs of locations and commissioned six artists to create all the dialogue scenes in original oil paintings and hand-drawn colored illustrations. Seven artists, from Bangladesh, Indonesia, Israel, Kazakhstan, China and England were hired to create original art for the film.

“The ‘jet engine’ of the film is its outstanding soundtrack. We went the extra mile in creating the music and sound effects and we auditioned over 100 voice actors to find the best cast possible.”

Rabbi Isaac Abarbanel (“The Abarbanel”) was raised in a world of privilege in Portugal, among nobility, and was educated in both Jewish and classical studies by his father, Judah Abarbanel, who was an adviser to the king in Castille, and by the best rabbis and teachers. Like his father, he became a man of many worlds.

Jonathan Ray, professor of Jewish Studies at Georgetown University, says in the film, “The persecutions, murder and forced conversions of Jews to Christianity… quickly spread throughout Castille and the neighboring Spanish territories …” Judah Abarbanel sought safety in Portugal with his family, he was appointed adviser to King Edwardu Duarte, and the Jews flourished.”

We see the complex historical wars that ensue, including bitter rivalries within royal families, and the Abarbanel always found himself at the eye of the storm. In the midst of all this he wrote his first books at the age of 20. Then he started working on his commentary on the Torah.

In the course of the upheavals and competing loyalties, Abarbanel had an edict issued against him in Portugal and he escaped to neighboring Spain. Many Jews who remained in Spain were Marranos, most of whom practiced their Judaism in secret. The Abarbanel continued writing his commentaries.

Yitzchak Gettinger, rabbi of the Young Israel of the West Side, New York, another commentator in the film, says: “The Abarbanel’s commentary and his passionate study of Torah have to be seen and understood in the context of how he saw the times he was living in, and the past history of Jewish exile, especially in Spain.”

Eventually Abarbanel’s family was able to leave Portugal and reunite with him in Spain, where he became the financial adviser to a Jewish bank in Toledo. He flourished there, where he continued writing his commentaries.

But King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella needed his financial expertise in helping to fund the war against the Muslims in Grenada. They asked him to be treasurer and adviser to the royal court of Spain. He thought that perhaps being close to power would help him to be a voice for the Jews at a time when the church was encouraging the king and queen to rid Spain of its foreign influences. In the year 711 the Muslims had invaded the Iberian Peninsula and ruled southern Spain until 1492. It is described in the film as a golden era for the Jews, when they lived in harmony with their Muslim neighbors.

A major challenge for Ferdinand and Isabella was the converso problem. According to Jonathan Ray, “Eventually they petitioned the pope to have their own Spanish inquisition.” It appeared that the golden age of the Jews in Spain was soon to come to an end.

In addition to Abarbanel finding the money to fight the ongoing war in Granada against the Muslims, the king and queen pressured him to find the money for Christopher Columbus’ expedition to India and the Far East, which would give Spain a larger share of the spice trade.

Torquemada, the grand inquisitor and the queen’s confessor, convinced her that any Jew who would not convert should leave Spain. Said Ray: “Technically the Inquisition didn’t have any power over professing Jews. They did have power over the ‘new Christians.’ … Conversos who were found guilty of heresy… were given the chance to recant, sometimes paying a large fine to the Inquisition; others were burnt at the stake. Torquemada believed that as long as there were real Jews helping them to be Jewish, the conversos would never be true Catholics, so in 1483 he begins to recommend the expulsion of the Jews.”

Granada fell in late 1491 and was back in Christian hands. The flag was raised over the Alhambra palace. Less than three months later, on March 31, 1492, the Edicto de Granada, the Alhambra Decree, was issued by Ferdinand and Isabella: All Jews must leave by the end of July and not return, on pain of death. Abarbanel and Abraham Senior, the chief tax farmer and an advocate for the Jewish community, raised 300,000 gold ducats and they hoped this feat would change the royal minds. It didn’t.

On June 7, 1492, Abraham Senior, and his family, converted to Christianity. An estimated 200,000 Jews, demoralized, also accepted baptism.

Approximately 100,000 Jewish men, women and children chose exile. The Abarbanel, proudly carrying a sefer Torah, was followed by thousands of Jews who began their journey to Palos and other ports to board ships that took them into exile.

Three days after the expulsion, on August 3, Rosh Chodesh Av, Christopher Columbus set sail from Palos to India, an expedition that Abarbanel had helped fund, and discovered the new world.

Abarbanel continued writing his commentaries. Toward the end of his life, he wrote in his introduction to his commentary on the Prophets: “I spent so much time serving mortal kings. I regret not having spent more time serving the King of Kings.” He died at age 71 in 1508.

On December 16, 1968, 476 years after it was issued, the Alhambra Decree was officially revoked by the Spanish government.

The cruel and tumultuous times covered in this film are long past, but the Abarbanel’s commentaries live on.

Anyone interested in pre-ordering the film can find information at www.rabbiwein.com or at 732-987-9008. When the film is available it will be found at www.rabbiwein.com/abarbanel

The reviewer is an award-winning journalist and theater director and editor-in-chief of www.WholeFamily.com.