Justice Barry T. Albin, highly esteemed for his brilliant legal acumen, retired from his position on the highest court of New Jersey on July 7, 2022. The trailblazing jurist, hard-working and heimish, reached the mandatory retirement age of 70, what he has referred to as the “constitutional age of senility.” During his tenure as an associate justice on the New Jersey Supreme Court, he authored more than 400 opinions, including over 230 majority opinions, more than 130 dissents, and dozens of concurrences.

Albin reflected on his legacy and noted that his majority opinion in Lewis v. Harris garnered the most attention out of all his written opinions. The decision handed down on October 25, 2006 guaranteed equal rights to same-sex couples under our state constitution.

The opinion that took Albin the longest to write was State v. Fortin. In October 2002, one month after taking his seat on the high court bench, he was assigned to write the majority opinion reversing a death penalty conviction. Albin believed in what he was writing and did not agonize when crafting his opinions.

During his last term on the bench, he said, “there were a number of controversial cases before the court.” Just before retirement, Albin wrote the opinions on two of what he termed “rule of law” cases. In one case, the court majority vacated a murder conviction, and in another granted parole to an inmate convicted of a murder that occurred 49 years earlier.

“The court is bound to protect the individual rights of people scorned by society, which often members of the public have trouble understanding,” Albin said, adding that courts in upholding fundamental rights, at times, must render unpopular decisions and resist the temptation to bend to public opinion.

Growing up in Queens, Albin attended Hebrew school in Flushing before moving to Bayside at age 10. He recalls donning tefillin, reading Torah and chanting the Haftorah in 1965 when he became a bar mitzvah.

While Albin was attending high school, his family relocated to Sayreville, New Jersey, along with several aunts and uncles and his grandfather who lived on the same block. He termed the difference in the population of the school and the surrounding neighborhood as “a culture shock.” In his new school, with a graduating class of 500, there was only one other Jewish student.

The son of American-born parents Norma and Gerald, Albin is the youngest of three boys. After Gerald returned from four years of service in the Coast Guard during WWII, he married in 1946 and was the father of three by 1952.

Albin’s early home life was happy and carefree. Neither his mother, a homemaker, nor his father attended college, yet both were well-read and bred in their children a love of reading. Although nothing was mentioned on the subject, it was expected and understood that his brothers and he would go to college.

While his brothers, Stuart and Robert both pursued careers in dentistry, Albin decided at a young age to be a lawyer. He decided on this path out of “a desire to do public service and make some positive difference in the world.” His love of history and English were his natural strengths.

Albin speaks lovingly of his grandparents and his weekly visits to their homes. They were all English-speaking, with some spatters of Yiddish, his maternal grandfather being the most religious. He relished a special relationship into his 20s with his grandfather, David Albin, who lived the longest of his four grandparents and lived on his block. Albin never attended sleepaway camp, instead, he recalled spending summers in the “Jewish Alps,” the Catskills. There, many family members crammed into his grandfather’s small house in the hamlet of Hurleyville.

After graduating from Rutgers College in New Brunswick in three years, Albin attended Cornell Law School. Graduating in 1976, he then returned to his home state to begin his career as a deputy attorney general in the Appellate Section of the New Jersey Division of Criminal Justice. He went on to serve as an assistant prosecutor in Passaic and Middlesex Counties from 1978 to 1982.

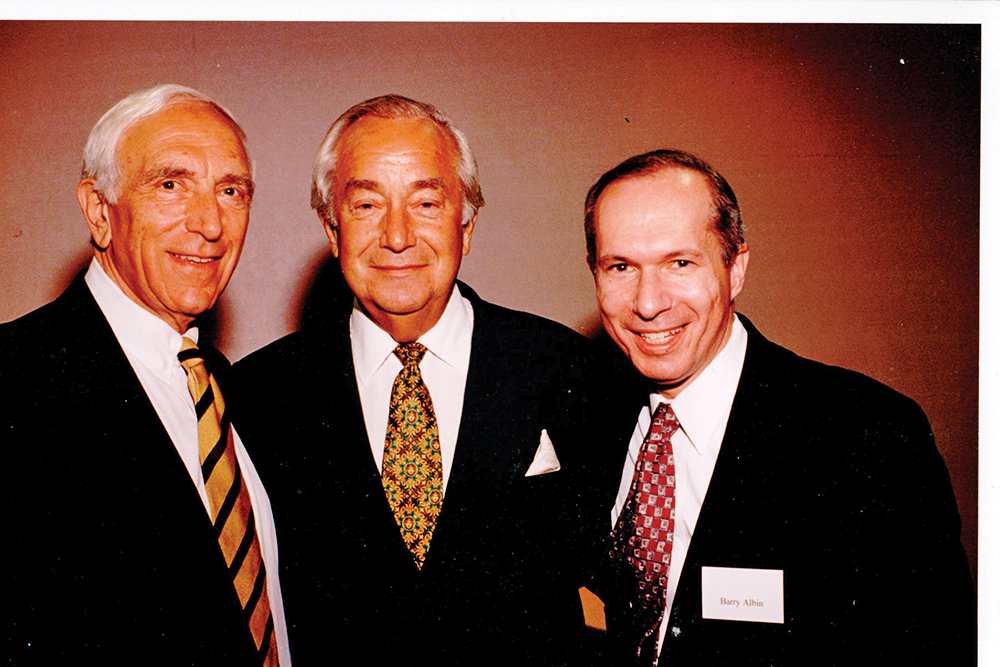

In those four years as an assistant prosecutor, Albin handled approximately 40 jury trials and gained a reputation as a fair and well-prepared attorney on the rise. Warren Wilentz met Albin as opposing counsel on a case. Not long after losing the case to the young Albin, Wilentz asked him to join his prominent Woodbridge law firm of Wilentz, Goldman & Spitzer (Wilentz) in 1982. Warren Wilentz became Albin’s mentor and friend. Albin rose to the position of partner in 1986 the old-fashioned way—through hard work and success in the courtroom.

For 20 years Albin practiced law in the private sector, handling criminal defense and civil rights cases as well as tort and employment law cases. With years in public service and private practice under his belt, and what he proclaimed as “a hearty work ethic,” he began to climb the ladder, culminating in a coveted position on the high court.

While working at Wilentz, Albin met and befriended Jim McGreevey. Albin became a mentor to McGreevey and when McGreevey first ran for governor, Albin offered him advice.

Albin thought that he might be asked to fill the position of attorney general, but as governor-elect, McGreevey broached the subject of a Supreme Court seat, which Albin stated, “took [him] by surprise.” Ten years earlier, Albin had been bypassed for the position of prosecutor of Middlesex County, a disappointment he did not regret. Those additional years allowed him to handle the most important work he did in private practice, which ultimately better served him for a position on the high court.

In 2002, Governor Jim McGreevey appointed Albin, age 50 at the time, to the bench. After serving his initial seven-year term, Albin was reappointed for a second term that ran until he reached his retirement age of 70. McGreevey, speaking at

Albin’s retirement dinner, quipped that Albin was too honest to be attorney general.

A look inside the day of a New Jersey Supreme Court justice reveals long hours and the need for competent staff. Throughout his years on the bench, Albin hired 60 law clerks from various law schools nationwide and well over 100 interns.

Cases before the New Jersey High Court are heard two days every two weeks from September through part of April. After hearing cases, the following Tuesday the justices sit around the table for discussion and a final vote. The chief justice then assigns a member of the majority to write the opinion. But there are many things the justices are responsible for in addition to deciding cases, including attorney discipline. The justices continue sitting through mid-July, writing opinions through August. Albin always set aside the last two weeks of August for family vacations.

Before joining the court, he had no preconceived notions about the work ahead, but Albin said that he was surprised that he was putting in more hours on the court than he did in private practice. Remaining dedicated to the work he was doing, whether writing a majority, dissenting or concurring opinion, Albin was always mindful that the outcome could affect the lives of not just the litigants, but thousands of other people, and would also serve as a precedent for future cases.

To Albin, a good judge treats lawyers and litigants with decorum and respect and is sensitive to the public’s perception of judicial impartiality. For that reason, he recused himself from cases if an attorney was a close friend. He also never sat on cases argued by his former law firm.

Although raised in a “fairly secular household,” Albin and his brothers “all attended Hebrew school, had a bar mitzvah and attended religious services.” He recalls Passover Seders at the homes of various relatives before the decades-long tradition of gathering at his brother Stuart’s home for Seders. He affirmed that “[my] upbringing played a role in the principles that guide me.”

Albin declared what he enjoys most about his profession is “the positive impact on the lives of other people and the ability to right some wrongs, giving people a fair shot in the judicial system.”

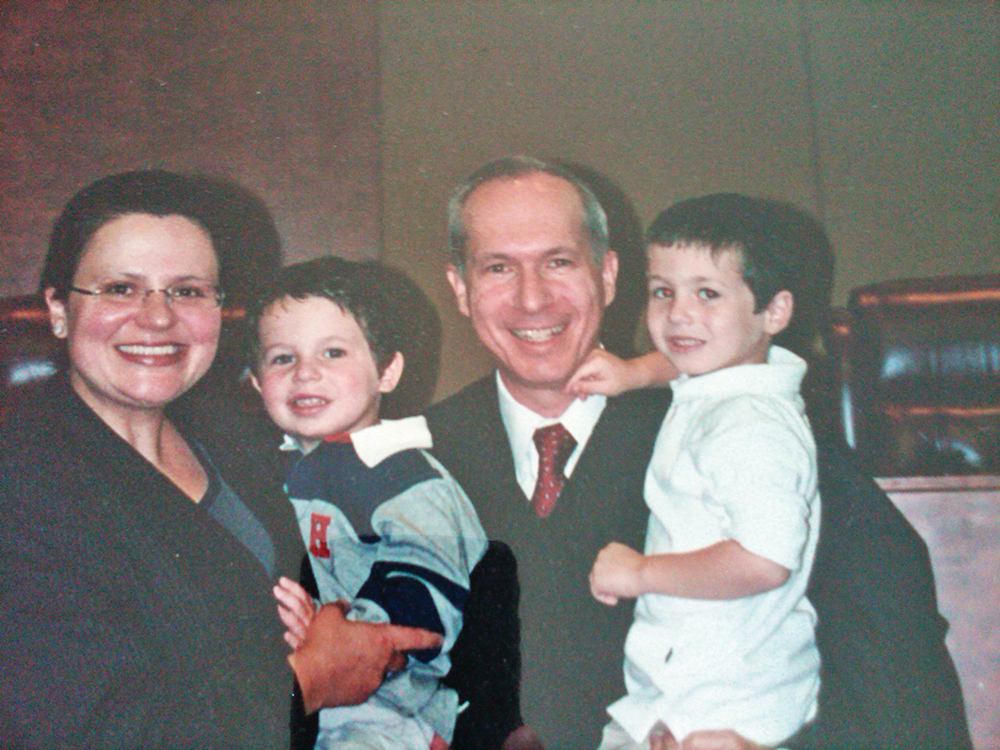

Throughout his career, Albin has remained a devoted family man, always supported by his wife, Inna, who is also an attorney. The couple has two sons, Gerald and Daniel.

His humility is refreshing, and his sense of humor is endearing. Albin’s optimism is front and center when he declares he is not concerned about the future of our courts, stating, “Our system of justice has safeguards to keep mistakes to a minimum. The layers of the court system weed out those mistakes. Yet, there is a constant quest to improve the system and make it fairer and more just.”

Albin is currently working as a partner in the litigation department of the national law firm Lowenstein Sandler in its Roseland, New Jersey office. Additionally, he chairs their Appellate Practice Group and serves as a neutral arbitrator and mediator in complicated, high-stakes disputes.

Sharon Mark Cohen, MPA, is a genealogist, historian and journalist who believes everyone deserves a legacy. Follow her Tuesday blog at sharonmarkcohen.com.