Pesach is just around the corner, so soon, you might meet with your rabbi to arrange the sale of chametz. At that meeting, he’ll probably give you a handkerchief and ask you to pass it back to him. What’s going on here? Did you just sell your chametz to the rabbi? Was there a kinyan (act of acquisition) that occurred with the transfer of the handkerchief? If so, was it when he gave you the handkerchief or when you gave it back? Judaism isn’t a religion of meaningless rituals, so it’s good to know what’s happening.

To explain, you’re not selling your chametz to the rabbi. You’re appointing your rabbi as your agent to sell your chametz. The rabbi acquires from you the right to act to sell the chametz, during one of those handkerchief handoffs, as a kinyan called “chalifin” (bartering), or “chalipin” in yeshivish or “kinyan sudar.” As Rav Herschel Schachter explained in shiur1, there’s a Talmudic dispute whether “chalifin” is performed with the vessel (e.g. handkerchief) of the koneh (one acquiring) or makneh (one transferring ownership), and we rule that it’s with that of the koneh. Therefore, the rabbi gives you his handkerchief, and, in exchange, you are granting him that right to sell your chametz. We can add that you now own the handkerchief, and you give it back to the rabbi as a gift, so that he can use it for the next person2.

Rav Versus Levi

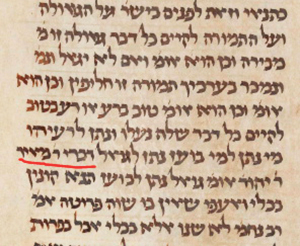

Our sugya (Bava Metzia 47a) records a dispute between first-generation Amoraim. Rav says that chalifin operates בְּכֵלָיו שֶׁל קוֹנֶה while Levi (ben Sisi), another of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s students, says it works בְּכִלְיוֹ שֶׁל מַקְנֶה. Rav Huna of Diskarta attacks Levi’s position, to Rava: isn’t a kinyan of both flowing in the same direction a “kinyan agav,” but land via moveable property, where a mishna taught that agav is only moveable property via land. Rava replies that if Levi were still around, he’d flog him with rods of fire (pulsa denura)—the direction is still the reverse of agav, since he’s receiving honor that the other party is accepting his gift. The Talmudic narrator then suggests that this Rav/Levi dispute parallels a Tannaitic dispute.

That is, in sefer Rut, Ploni Almoni declines to redeem the field and perform customary levirate marriage on Rut. The author interjects that a practice to establish any matter was שָׁלַ֥ף אִ֛ישׁ נַעֲל֖ו— “a person removed his na’al,” וְנָתַ֣ן לְרֵעֵ֑הו— “and gave it to his fellow.” The story proceeds: Ploni tells Boaz acquire for yourself, וַיִּשְׁלֹ֖ף נַעֲלֽוֹ— “and (he) drew off (his) na’al.” Now, these “he” and “his” pronouns have ambiguous antecedents, whether it was Ploni or Boaz who drew off his own na’al, as well as who is אִ֛יש and who is רֵעֵ֑הו. In a baraita, the Tanna Kamma says Boaz gave his na’al to Ploni (thus acquiring the rights to marry Rut), while fifth-generation Tanna Rabbi Yehuda says that Ploni gave his na’al to Boaz3. The full context of the baraita seems halachic, rather than concerned merely with narrative details, so it stands to reason that this was indeed about בְּכֵלָיו שֶׁל קוֹנֶה/מַקְנֶה. Also, while most texts—as well as the parallel Yerushalmi—Kiddushin 1:54, have an anonymous Tanna Kamma, Florence 8-9 has fifth-generation Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehuda’s frequent disputant, say this.

Later in the Gemara—fourth and fifth-generation Amora—Rav Sheisha bar Rav Idi (bar Avin) explains terms used in his contemporary documents which related that the kinyan chalifin was performed. בְּמָנָא דְּכָשַׁר לְמִקְנְיָא בֵּיה—“vessels fit to acquire with,” doesn’t accord with Rav Sheshet (but with Rav Nachman), that vessels—not produce—must be used. Either he or the Talmudic narrator then interpret other phrases of the document, so לְמִקְנְיָא—“to acquire,” serves to exclude Levi, who should say “to transfer.”

Who wins? After all, Rava was willing to defend against attacks on Levi. The Rif, Rosh and Numukei Yosef all write that we rule like Rav, firstly because the stam, that is the Tanna Kamma accords with him, while Rabbi Yehuda—who is an individual—accords with Levi. (If it’s instead Rabbi Meir, that would undermine this argument.) Further, the conclusion of the Gemara (that is, interpreting terms of the document) accords with Rav.

‘Na’al’ as Sandal

So far, I’ve avoided translating “na’al.” It is commonly understood as a shoe/sandal. This works well, to my mind, because it calls to mind Moshe removing his na’al from his foot by the burning bush (Shemot 3:5), שַׁל נְעָלֶיךָ מֵעַל רַגְלֶיךָ— “Remove your sandals from your feet,” even though שַׁל is only the prefix of שָׁלַ֥ף. It also calls to mind Devarim 25:9, וְחָלְצָ֤ה נַעֲלוֹ֙ מֵעַ֣ל רַגְל֔ו, about “chalitza.” Even though what occurs in sefer Rut seems to be mere customary “yibbum,”—rather than halachic—and the closer redeemer would not need to perform chalitza, making it a sandal that resonates nicely.

On the other hand, it seems strange to modern ears that someone removes and hands over their sandal to accomplish a kinyan. Does he hop home? The Targum to Rut renders נַעֲל֖וֹ as נַרְתֵּיק יַד יַמִּינֵיה—“his right glove.” This calls to mind investiture in a feudal society, where the lord would symbolically surrender the fief (estate of land) to his vassal. After homage—in which the vassal would declare himself to be his lord’s “man”—they would perform this investiture, in which the lord would hand over an item such as a staff, glove or ring. This may have roots in real estate acquisition procedures in the Frankish period—where the acquirer received an object symbolizing possession of the land—such as a clod of earth, a tree branch, a grain stalk, staff or a glove5. In turn, this reminds me of the controversial kinyan of mesira (as discussed in my Jewish Link article, “Acquisition via Reins,” December 21, 2023), which transfers ownership by transferring a symbol of dominion over the target, e.g., the bucket of a well, the key of a house or the bellwether of a flock6. In turn, this glove interpretation would reinforce a Levi-oriented reading of chalifin.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 https://yutorah.org/lectures/1030907 at the 10 minute mark.

2 My father quotes his teacher in a practical rabbinics course: a rabbi should have two handkerchiefs, one for chalifin and the other to blow one’s nose, and it was critical not to mix up the two.

3 Shita Mekubetzet cites the Rosh that Rabbi Yehuda’s interpretation seems more like the peshat, that the same actor who said “acquire” continues with the next action, drawing off his sandal.

4 In that Yerushalmi, it’s perhaps unclear which position is taken by Rav and which by Levi. But they point to the Bavli, תַּמָּן אָֽמְרִין, and say that Rav and Levi weigh in directly on who removes the na’al, as koneh versus makneh.

5 See Encyclopedia.com entry on Investiture

6 Then, we’d proffer an alternative answer than Rava’s to defend Levi, offered by the gemara in other contexts. What matters is which type of kinyan is being invoked, e.g. Kiddushin 8a, acquiring something בְּתוֹרַת כֶּסֶף vs. בְּתוֹרַת תְּבוּאָה וְכֵלִים, that is, chalifin. If we invoke agav, then it wouldn’t work, but if we invoke mesira or chalifin, it would work. Also, see Kiddushin 7a, Rav Ashi and Mar Zutra, with explicitly invoking agav vs. benefit for receiving.