Conclusion

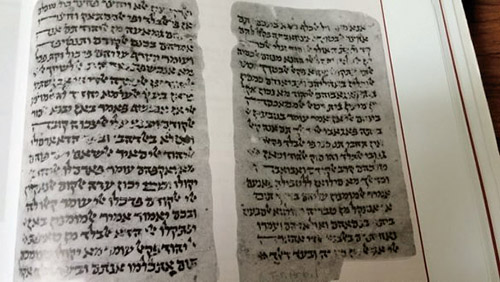

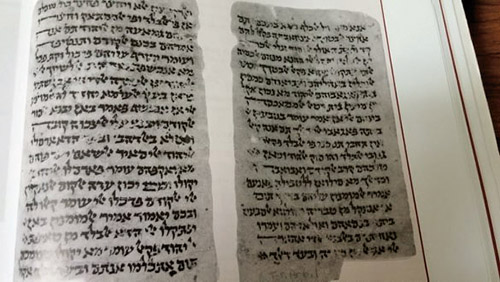

A Judeo-Arabic chronicle from the Cairo Genizah (circa 11th century) describing how the Jews assisted Omar in cleansing the Temple Mount and the renewal of Jewish settlement in Jerusalem.

At the time of the Arab conquest of Jerusalem in circa 638, the city was garrisoned with Byzantine Christian troops. No Jews had been allowed to reside in the city since the quelling of the Bar Kochba revolt by the Romans in the year 136. During much of the period that marked Jerusalem under Christian rule, the Temple Mount was neglected and it was used as a garbage dump (though at some point the Byzantines did apparently build a church or a monastery atop the mount).

The Jerusalem-based Karaite Salmon ben Yeruham (10th century) in his commentary to Echah, the Book of Lamentations, writes on the verse “Jerusalem is as a menstruous woman among them”: “That is what Edom have done when they destroyed the Second Temple, for all the days of their stay here they would discard therupon [the site of the temple] the menstrual cloths and the refuse and all kinds of filth.”

According to the Arab historian Tabari, the conquering Arab general Omar treated Jerusalem’s newly conquered Christian inhabitants with magnanimity. He even wrote them a letter wherein he promised that the churches would not be touched and that no Jew shall reside in the city. This, as we saw, was important to the Byzantines as the Jews’ continued banishment from their holiest site confirmed their belief in the eternal guilt of the Jews.

This writ was certainly not honored. Some cast doubt as to the authenticity of it altogether (particularly Goitein); others propose that originally the Muslims sought to placate the Christians but eventually reversed their policy (perhaps since it made more sense for the Muslims to have a substantial Jewish rather than Christian presence in the Holy City).

According to Gil, Muslim traditions ascribe special significance to Caliph Omar’s visit to the Temple Mount. Most of them add to his entourage on this visit Kab al-Ahbar, a Jew from Southern Arabia who turned to Islam and was considered an authority on matters of the Jews and their Torah.

Kab explained to Omar that the entrance to the place [mount] and the evacuation of the refuse from the mount is the fulfilment of the 500-year-old prophecy that foretold the rise of Jerusalem and the fall of Constantinople. Omar ordered the Muslims to clean up the place and the Jews helped them do so. Twenty Jewish families were said to have been given this privilege and were permitted to reside in the area and not pay any taxes.

On the readmittance of the Jews to Jerusalem, Omar apparently decided to adopt a pragmatic approach wherein he allowed a limited number of them so as not to irritate the Christians. What is certain, though, is that the resettlement of Jews in Jerusalem occurred shortly after the Arab conquest. In a letter from the Cairo Genizah dated to the 11th century (see photo), we find the passage “And from our God that befell his mercy upon us before the kingdom of Ishmael; at the time when their power expanded and they captured the Holy Land from the hands of Edom and came to Jerusalem, there were people from the Children of Israel with them; they showed them the spot of the Temple and they settled with them until this very day.”

Jews assisted Muslims in disposing of the refuse on the Temple Mount and several Jews were officially appointed to be responsible for its cleanliness. One source has Omar overseeing the project and “whenever a remnant was revealed, he would ask the elders of the Jews about the rock, namely the ‘even shteiya’ (the foundation stone), and one of the sages would mark the boundaries of the place until it was uncovered”.

Other non-Jewish sources have the Jews establishing a spot for prayer on the Temple Mount, perhaps even building a (makeshift) synagogue there.

The name of the city during the early Islamic period was “Bayt al-Makdas,” which is an abbreviated form of “Madinat Bayt Al-Makdas,” which naturally means the “city of the Holy Temple.” Later the name would be abbreviated to “Al Quds.” It is interesting to note that the word “quds” comes from the Hebrew “kodesh” and has no meaning in Arabic.

The contemporary Islamic sources didn’t ascribe great significance to Jerusalem or the Temple Mount (for Islam). Jerusalem, for instance, is not mentioned by name in the Koran. While Jerusalem would eventually become the third holiest site in Islam, this was not always the case (some Shias still count Kufa in Iraq as the third holiest site).

Omar apparently built a simple Islamic shrine on the Temple Mount that did not gain any particular distinction at the time. It was only later, 50 years after Muhammad’s death, that Abd al-Malik, the Umayyad caliph, built what we now know as the Al-Aqsa Mosque, claiming that “Al Aqsa” mentioned in Sura 17 (literally “the farthest”) referred to the Temple Mount.

The Dome of the Rock was built in circa 690 over the Foundation Stone, the actual site of the historic Jewish Temple. During the entire Muslim period Jerusalem was not the capital of the region; that distinction was reserved for cities like Casearia, Lod and especially Ramla. When the Crusaders wrested Jerusalem from the Muslims at the end of the 11th century, Jerusalem again became an important rallying cry for Islam. This would repeat itself with the establishment of the State of Israel.

By Joel Davidi Weisberger

The author is an independent scholar of Jewish history and can be reached at yoelswe@gmail.com. Check out Channeling Jewish History on Facebook.