The Megillah (Esther 9) mentions obligations of the day of Purim, which include making it a י֖וֹם מִשְׁתֶּ֥ה וְשִׂמְחָֽה, a day of feasting and merrimaking; וְי֣וֹם ט֑וֹב, a holiday—though that was not truly accepted in terms of refraining from labor; וּמִשְׁלֹ֥חַ מָנ֖וֹת, sending portions from the meal to your friend; וּמַתָּנ֖וֹת לָֽאֶבְיֹנִֽים, alms for the poor; נִזְכָּרִים וְנַעֲשִׂים, interpreted as reading the Megillah.

These don’t seem to include an obligation to become inebriated on Purim, until one is unable to distinguish between “cursed be Haman” and “blessed be Mordechai.” I also have not seen explicit mention of an obligation to get drunk in Tannaitic works or in Talmud Yerushalmi. There’s not only absence of evidence, but in Nedarim 49b, potentially evidence of absence: “Rabbi Yehuda explains to a Roman matron that it’s his wisdom that makes his face ruddy, not wine that he drinks. ‘Indeed, I only drink the wine of kiddush, Havdala and the four cups on Pesach, which gives me a headache until Shavuot.’” Purim is curiously absent, unless the wine-headache precludes simcha and exempts Rabbi Yehuda from drinking.

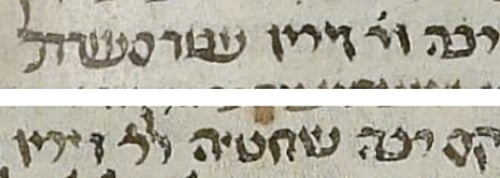

On Megillah 7b, Rava, a fourth-generation Amora, makes this famous statement about the obligation: מִיחַיַּיב אִינִישׁ לְבַסּוֹמֵי בְּפוּרַיָּא עַד דְּלָא יָדַע בֵּין אָרוּר הָמָן לְבָרוּךְ מָרְדֳּכַי, with לְבַסּוֹמֵי meaning “become inebriated.1” Whatever the nature of the laws of Purim, I wouldn’t expect a late Amora like Rava to entirely fabricate a new law. Presumably, he deems it grounded and implicit in the יוֹם מִשְׁתֶּה וְשִׂמְחָה. After all, “mishteh” most literally means “drinking.” I’d guess that feasts included celebratory drinking, and so such meals were called “mishteh” through metonymy. Achashverosh’s feast included excessive drinking. Also, elsewhere, Chazal describe שִׂמְחָה—joy, as achieved through drinking wine.

Rava seems to have had a role in situating the “feast” aspect of Purim more centrally. On the same daf, on Purim day, sixth-generation Rav Ashi sat before his teacher, Rav Kahana IV (of Pum Nahara), a fifth-generation student of Rava. Rav Ashi wondered why the other members of the academy weren’t present. Rav Kahana suggested they were occupied with their Purim feast. Rav Ashi: “Couldn’t they have had the feast at night?” (In that way, they could have focused on Torah study during Purim day.) Rav Kahana said: “Didn’t master learn Rava’s statement, that a Purim feast at night doesn’t fulfill one’s obligation.” (After all, the verse discusses “days” rather than nights of feasting and gladness.) Rav Ashi then committed this teaching firmly to memory.

Obligation Not Absolut

Despite Rava’s uncontested halachic drunkenness threshold, not all Rishonim and Acharonim establish it as the literal inability to distinguish between “cursed be Haman” and “blessed be Mordechai.” For instance, Rambam (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Megillah 2:15) lists it alongside/part of the nature of the Purim feast, stating וְשׁוֹתֶה יַיִן עַד שֶׁיִּשְׁתַּכֵּר וְיֵרָדֵם בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ, that he should drink wine until he becomes inebriated and falls asleep drunk; similarly Maharam miRotenberg.

Rav Yosef Karo stresses, in Beit Yosef, that such a level of intoxication would constitute an absolute sin. Rather, one drinks more than regular. How does this fit with Rava’s words? And why does he record the simple words without such explanation in Shulchan Aruch? (The answer is that he regularly expected people to read Beit Yosef and then understand the terser Shulchan Aruch in that light.)

Some suggest Rava’s requirement is lemitzvah, a higher fulfillment level, rather than leikuva, a basic minimum fulfillment threshold. But, does this fit with the language מִיחַיַּיב? Others suggest that “Arur Haman” and “Baruch Mordechai” were words to a Purim song/piyut—thus, one messes up the complicated words. They point to Tosafot who quotes a longer text from the Yerushalmi. Others say Rava meant reflecting on the relative goodness arising from a “Baruch Mordechai” versus “Arur Haman.” There are indeed several valid ways of interpreting Rava’s words so that he’s not literally requiring/endorsing such drunkenness.

I’ll add two more. My father points out that בְּפוּרַיָּא not only means “on Purim” but can mean “in your bed”, thus yielding Rambam’s explanation of drifting off to sleep. I’d suggest that Rava was in a playful and creative mood. He will employ expressions like (Sanhedrin 74b) לִיקְטוֹל וְלָא לִקְטְלֵיהּ, that a Jew threatened by a gentile with death if he doesn’t mow grass on Shabbat should cut and not be killed. Of course, Rava didn’t literally mean not possessing such basic mental capacity to distinguish—that would approximate the drunkenness of Lot! We should recognize the genre of Rava’s expression, and how Rava playfully draws on Purim themes to mean that the person should become quite drunk—just not to that literal extent.

Interjecting Arur Haman

I couldn’t find the exact language Tosafot mentioned in Yerushalmi, namely ארורה זרש ברוכה אסתר ארורים כל הרשעים ברוכים כל היהודים. This might be because of variant texts, or because “Yerushalmi” sometimes means midrashim, especially Bereishit Rabba, the midrash aggadah of the Amoraim of Eretz Yisrael. Yerushalmi Megillah 3:7 states that one should read Haman’s sons’ names in one breath. Shortly after, Rav says that one must say “Haman be cursed, his sons be cursed.” Rabbi Pinchas adds that one should say, “Charvona should be remembered for good.” Rabbi Yonatan—when reading “Nebuchadnezzar” in Esther 2:6—would add “may his bones be pulverized.”

Bereshit Rabbah 49:1 is clearer—when Rav reached the name Haman (in the Megillah), he would say “cursed be Haman and cursed be his sons,” fulfilling Mishlei 10:7, “and the names of the wicked should rot.” Rabbi Pinchas said, regarding Charvona, “remembered for good.” Similarly, Rabbi Yonatan and Nevuchadnezzar, in the Megillah. The context is Rabbi Yitzchak’s statement that anyone who mentions a righteous person’s name and doesn’t bless violates the first half of that verse in Mishlei, זֵ֣כֶר צַ֭דִּיק לִבְרָכָ֑ה, and one who mentions a wicked person’s name and pronounce a curse violates וְשֵׁ֖ם רְשָׁעִ֣ים יִרְקָֽב.

Not during a piyut, but during Megillah reading, the listeners/readers would interject blessings and curses when encountering each positive or negative figure, even a minor one like Charvona. The reading was participatory, much as nowadays we spin our graggers upon hearing Haman’s name.

Rava’s statement could imply that they were drunk even during Megillah reading, and might have accidentally shouted out an “Arur” or “Arur Haman” when reaching the name “Mordechai.” The degree of intoxication would be relevant to the night’s or day’s reading, rather than the festive meal; or, at least poetically,2 how one would have erred if hypothetically drunk during the Megillah reading.

Rabba and Rabbi Zeira

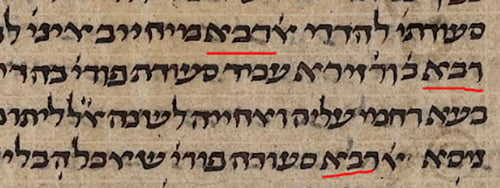

Let’s consider Rabba/Rava’s Purim feast with Rabbi Zeira I/II. Following Rava’s declaration of required intoxication level, third-generation Rabba and Rabbi Zeira I enjoyed a Purim seuda together, and they both became intoxicated. Rabba arose and slaughtered Rabbi Zeira. The next day, beseeched Hashem for mercy and revived him. The next year, he (presumably Rabba) said to him, “Let Master come and we’ll enjoy the Purim feast together.” He declined, replying, “Miracles don’t happen every hour.”

The Vilna printing and Munich 95 manuscript have Rabba in both occurrences in this story (the invitation and the slaughter)—with a line break between them—and Rava in the immediately surrounding halachic declarations about intoxication level and daytime feast. All other printings (Venice, Pesaro) and manuscripts (Munich 140, Gottingen 3, British Library 400, Columbia 294-295,3 Oxford 366, Vatican 134) on Hachi Garsinan have Rava interact with Rabbi Zeira, matching Rava’s appearance in the surrounding passages. We might follow after the majority.

Alternatively—following lectio difficilior potior (“the harder reading is stronger”) considerations—I prefer a rougher text with Rava before and after, and Rabba in the middle story, to a smooth when scribes are motivated to smooth out irregularities. Of course, a scribe might not have known of Rabbi Zeira II and so changed Rava to Rabba to make the feast participants contemporaries.

We’ve recently discussed how Rava or Rabba sent a nontalkative golem to Rabbi Zeira I or II in Sanhedrin. If e.g., Rabba partied with Rabbi Zeira I, perhaps he’s more likely to be the one to send him a golem; the identifications in these two sugyot could be related. I’ve seen such proposed connections between Sanhedrin and Megillah, such as that Rava admitted theological defeat about creating a golem; otherwise, he’d have resurrected him as he resurrected Rabbi Zeira. I disagree. Even if these are the same people, and even if Rabbi Zeira’s utterance wasn’t mere disapproval but turned the golem to dust, still, the Rabbi Zeira’s resurrection was via prayer to Hashem, not Rava’s established skill; miracles don’t happen every hour.

Finally, if Rava partied with Rabbi Zeira, he fulfilled his own dictum/threshold, and the disaster and Rabbi Zeira’s subsequent refusal could represent a rejection of this requirement. Conversely, if Rabba partied with Rabbi Zeira, then there’s broader and earlier basis for fourth-generation Rava’s practice.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Compare Rabba’s and Rabbi Zeira’s intoxication immediately below in the sugya, as אִיבַּסּוּם. But contrast with “consuming great amounts of sweets” immediately above in the sugya, as רַוְוחָא לִבְסִימָא שְׁכִיחַ—“There’s always room for dessert.”

2 If poetic, we needn’t grapple with questions like how Rava thinks people could become drunk during Taanit Esther—a Geonic fast, where Chazal had instead the holiday of Yom Nikanor; or the belief that Chazal established (Brachot 4a) that one may not eat and drink before performing any mitzvah, rather than making a decree for specific targeted situations, as I discuss at length elsewhere; or whether uttering “Arur”/“Baruch” would create an invalidating interruption.

3 Columbia has ראבא invite and רבא kill, with רבא surrounding, which might also imply Rabba.