On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Jan. 27, 2025, the world marked 80 years since the Jan. 27, 1945 liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp by the advancing Red Army. Though the end of the war in Europe wouldn’t happen until months later, the liberation that day was a mark in the sand that led straight through to Germany’s unconditional surrender in May 1945.

But the Holocaust, in its scale of horror and destruction, encompasses more than just Auschwitz.

It’s the Nuremberg Laws, Kristallnacht, and the Warsaw and Lodz ghettos—and hundreds more scattered throughout Nazi-occupied Europe.

It’s the killing fields and shooting pits of Babi Yar, Riga, Vilna and thousands more towns, big and small, in the vast “Holocaust by bullets” by Nazi Einsatzgruppen that began in 1941.

It’s the concentration camps of Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen, Sachsenhausen and Stutthof, Majdanek and Mauthausen among so many others, and the extermination camps of Operation Reinhard—Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka—from where only a handful survived out of millions slaughtered. The lives of people who perished there were extinguished so completely that for most there remains no trace of their existence. Not even the site of their murder was left to bear witness to the massacres that took place on those grounds.

It’s Jews hiding with false identities in the farms and convents of Righteous Gentiles or seeking refuge in a secret annex in Amsterdam.

It’s the hundreds of slave labor camps where Jews toiled with starvation rations while being worked to death, and the Hungarian slave labor battalions whose draftees served as human cannon fodder for the Axis Army battlefields.

It’s yeshiva students relocated to safety in Shanghai, children on the Kindertransport to England in 1938-1940, and “Tehran Children” to Eretz Israel—British Mandate Palestine in 1943. It’s the “Ritchie Boys” leveraging their knowledge of the German language to undermine Nazi battle plans and interrogate German POWs, the partisans furtively hiding in forests and the desperate escapees on the St. Louis and to Kenya.

And it’s the cattle car transports to Auschwitz and other deadly destinations, the selection ramp overseen by Dr. Mengele, the infamous Angel of Death, the sadistic daily Appell roll call and ghastly human medical experiments. And the “death marches,” the final blow for many who had survived years of hell only to succumb in the final weeks of the war.

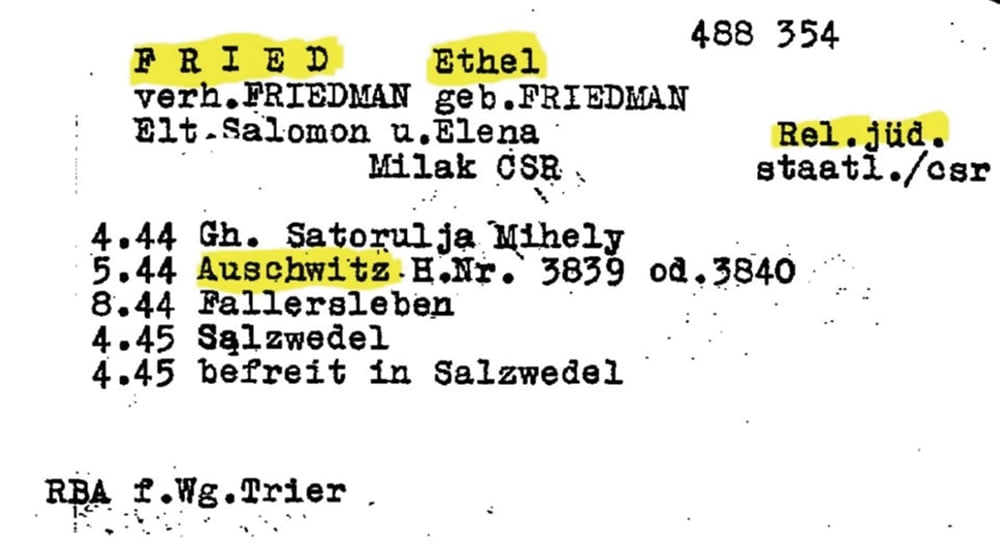

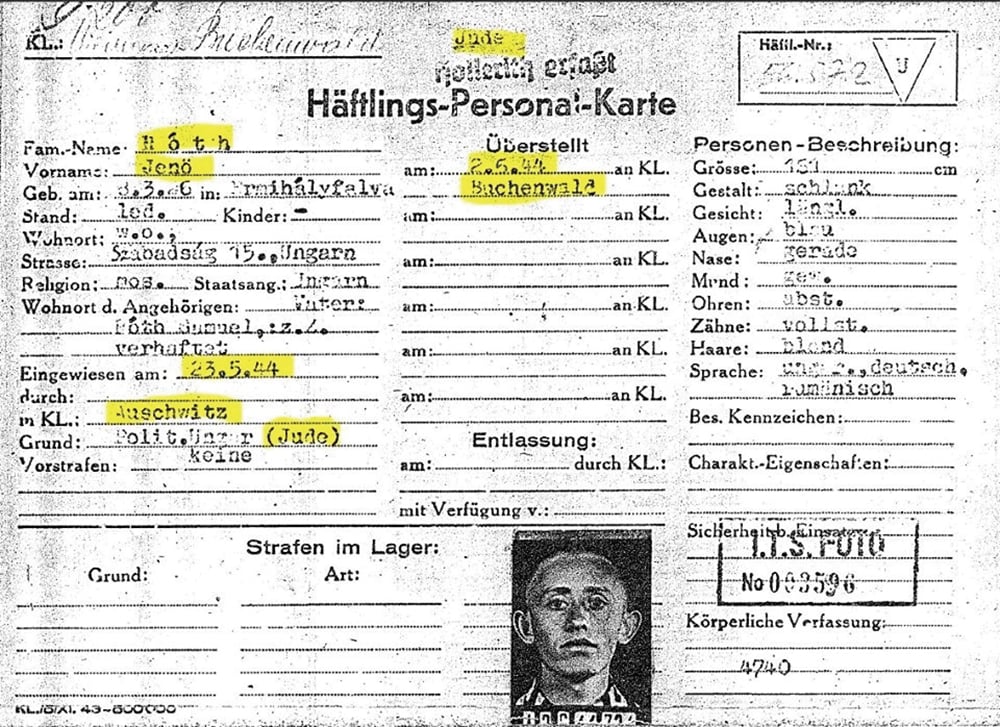

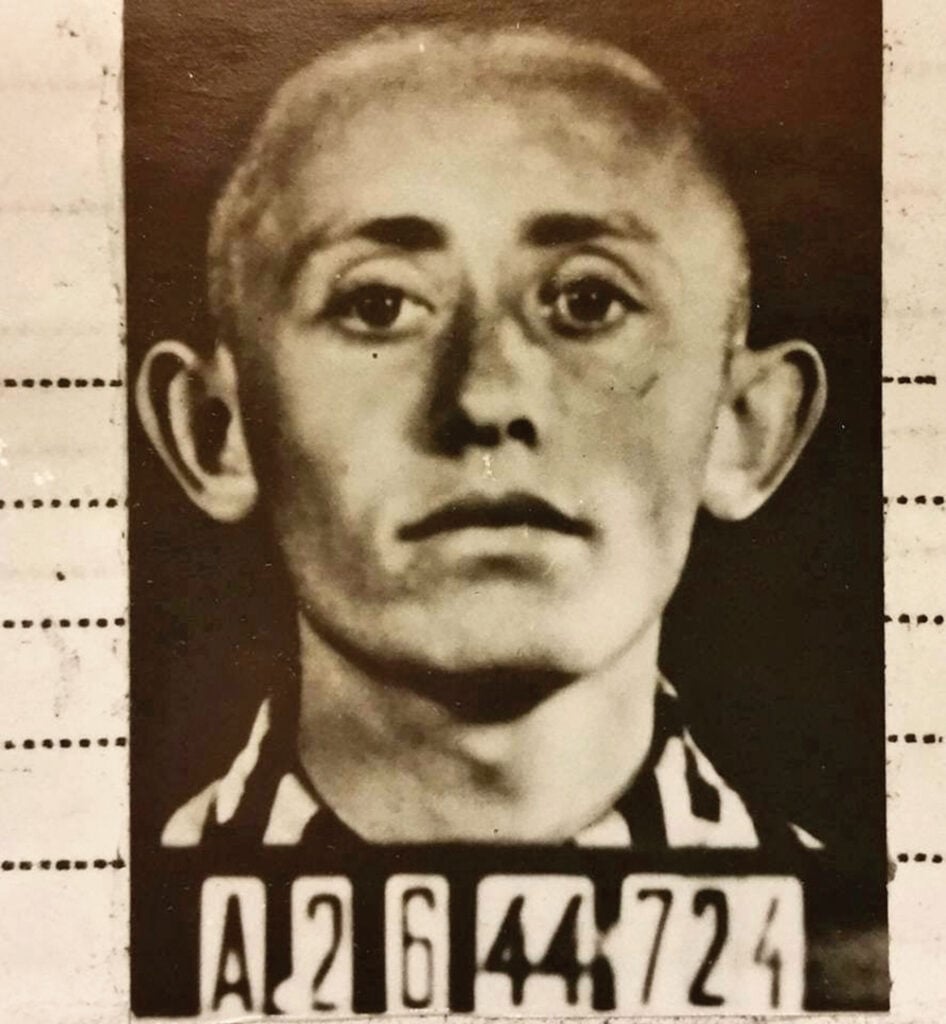

It’s these latter events that were the family history on which my sisters and I were raised, hearing about Mom’s family transported from Slovakia to Auschwitz on May 23, 1944, and Dad and his family deported from Romania, and arriving to the same selection ramp at Auschwitz on May 25, just two days after Mom and her family.

The enormity of the extermination is too vast to sum up with just one massacre, one solitary crime at one place over a single year.

We humans need symbols and visualization aids to enable a semblance of understanding of the incomprehensible. In the early years after the end of WWII, there wasn’t yet a formal name for the greatest genocide the world had ever witnessed. In fact, even the world “genocide” had to be coined in 1944 to describe what was becoming obvious as the Crime of the Century. The title of “Holocaust” did not evolve until years after the events themselves took place. My sisters and I didn’t know that the survival stories told to us by Mom and Dad when we were children were about the “Holocaust.” To us, it was simply The War.

But by 2005 when a formal international Day of Remembrance was first established, the day that Auschwitz was liberated was chosen to mark that which is vast and vague, and to clinically symbolize a crime that is utterly unfathomable and incomprehensible.

And that is what Auschwitz has come to represent.

It is a name that is fitting in sound, with a composition of vowels and consonants somehow forming a word that cannot be whispered. Its pronunciation is naturally guttural, harsh and punishing, evoking auditory images of the horrors that befell millions who passed through the gates that cynically declared, “Arbeit Macht Frei.” It is the perfectly ugly one-word name for crimes too hideous to describe.

But what humankind needs to remember is the Holocaust does not equal “just” Auschwitz. The world needs to recognize a true genocide when it occurs and understand what the word itself means so that it doesn’t become watered down and lose its meaning.

And it needs to view Auschwitz—and today’s International Holocaust Remembrance Day—as a symbol that is but one single place in a vast field of crimes that began to take root years before it exploded in size to become the monstrosity known as the Holocaust that the world recognizes today.

#RememberThis #WeRemember #NeverForget

Rifky (Arlene) Atkin is a technology program manager at Johnson & Johnson, and lives in Edison with her husband, Jack, where they raised their four children who are now grown with families of their own. She is the child of two Holocaust survivors and lost all four grandparents and hundreds of extended family members in the Shoah.