A timely and informative cybersecurity event was held at the Jewish Federation’s Paramus headquarters in early March. Lieutenant Jeff Angermeyer and Detective Alex Yannuzzi of the Cybercrimes Unit of the Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office were the evening’s speakers. Their warning, hammered home early and often, was “There is very little hacking in the world, but a whole lot of tricking.” Stated differently, it doesn’t matter how sophisticated an organization’s encryption or backend firewalls are if an employee is fooled into downloading malware through the front door. The message was particularly relevant for this audience, which was largely comprised of those charged with providing computer system protection for their respective organizations.

The evening began with Debbie Gottlieb, manager of the Kehillah Cooperative at the Federation, reminding those present of deadlines for federal and state security grants. On the federal side, the funds can be significant, having averaged $150,000 per organization last year. Gottlieb reminded audience members that Homeland Security grant applications will be made available around April 16, offered tips on how to apply for state grants, then switched gears by introducing the Federation’s newest employee, Gerard Dargan, who is director of Jewish community security.

Dargan has spent the last 26 years in law enforcement, the last 18 of which were in the Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office. Most recently, he was captain of the Criminal Investigations Division. In his new role he will oversee the security operations of the Northern New Jersey Jewish community, which will also include emergency and disaster response planning. In effect, he will be the liaison between Federation leadership and state law enforcement.

When it was Angermeyer’s turn at the podium, he began with some remarkable facts that drove home his unit’s physical boundaries of responsibility. He noted that there are nearly a million residents in the 70 towns comprising Bergen County, making it larger in population than five U.S. states. The George Washington Bridge, which, as we know, connects the county with New York City, is the most heavily trafficked bridge in the world. He explained that his unit is an outreach center for law enforcement for each of the 70 towns, doing work that the local municipalities are not equipped to handle. Its mission statement includes investigations, forensics and community education. He stressed to audience members that “as both officers of organizations and as individuals, you need to own your digital footprint.”

Angermeyer noted that phishing, viruses, frauds and breaches are only getting worse each year. He identified ransomware and cryptojacking as the two biggest types of malware today, briefly defining each one. The ransomware process begins when individuals are lured into clicking on a bad link, which locks their computers. They are then forced to pay a ransom in the form of cryptocurrency to have them unlocked.

Cryptojacking tricks a user into downloading malware, which slows the computer by using the device’s resources such as its CPU. Once inside, offenders can use the host computer to enrich themselves by mining cryptocurrencies.

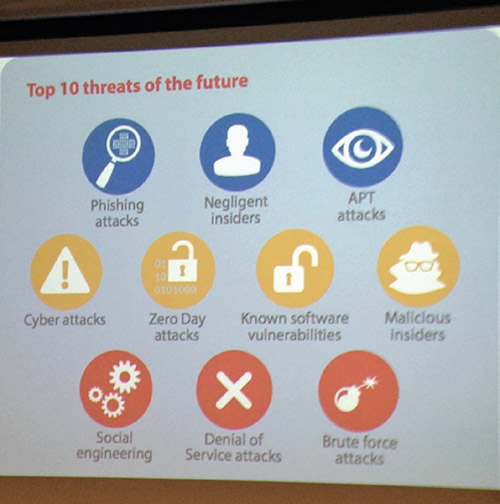

Angermeyer and Yannuzzi then reviewed a slide with a graphic showing the top ten threats of the future, with the vast majority falling within three areas: advanced persistent threat (APT) attacks, negligent insider and phishing. The first is aimed at sectors with high-value information, such as government or the manufacturing or finance industries. The second, negligent insider attacks, takes advantage of weak links in a company or organization. The massive attack at Target stores a few years back was a classic example. An employee was lured into clicking an email attachment, which then launched a data breach involving personal information for 70 million customers. Angermeyer focused on the third form of attack, phishing and spear phishing scams, noting that “95 percent of all attacks on enterprise networks are the result of successful spear phishing.”

He went on to explain the differences between the general and specific forms of phishing. General phishing, as the term implies, casts a wide net with the intent of trapping the unsuspecting. The trap may be via an email, a text message, a Facebook post, or other means. The goal is to reach as many people as possible in the hope that a few will take the bait and reveal personal information. Spear phishing is more targeted. Often the person trying to gain access to sensitive information knows something about the intended target based on information obtained from previous breaches. The message usually appears to be from a trusted source, such as a well-known company or website. The malware can even be disguised as security software, warning potential victims that they have just accessed an infected site, and if they don’t immediately click the link or call the phone number provided they may lose all data on their computer.

Angermeyer and Yannuzzi spent the remainder of the presentation detailing steps necessary to protect an organization’s computer system. To begin with, “Every entity, large or small, has a fiduciary responsibility to protect data.“ Schools and synagogues need to develop a detailed plan and can be sued if data is compromised because they didn’t have one. They must engage an IT expert or outside vendor, should demand continuous audits and reviews, must have strong password and password-change policies in place, and need a viable backup strategy.

Regarding passwords, the advice was to create separate and strong passwords for each website, with an absolute minimum of seven characters, including letters, numbers and characters. The usage of a password manager with one master password was recommended for safe storage. They stressed that for a synagogue or other religious organization that processes payments, it’s crucial. Daily backups, cloud or otherwise, are a must as well. In the case of a ransomware attack, the loss of data is limited to what was entered since the previous backup.

Also discussed was the need to educate people on how to recognize a phishing scam. Often seemingly from well-known companies, complete with logos, the warning signs can include an email that’s generic, a message involving a sense of urgency to act, or threats that an account will be closed if the message is ignored. Yannuzzi recommended that audience members hover over the provided link before clicking on it. “That action will reveal where the link is directed, which may not be where you thought it was going.”

By Robert Isler

Robert Isler is a freelance writer focusing on issues related to the Jewish world and Israel. He can be reached at robertisler23@gmail.com.