Finally, on Nedarim 10a, we learn what a kinuy, nickname, for a neder is! The first Mishna (2a) had declared that such nicknames were as valid as the direct neder, but then interjected with examples of shorthands (yadot) for neder—a point raised immediately by the Gemara1. At long last, the Mishna now discloses nicknames for neder, cherem, nazir and shevua. For neder, these are קוּנָּם קוּנָּח קוּנָּס, in place of korban. It is cherek, cherech or cheref in place of cherem, and so on.

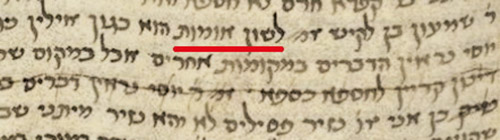

Rabbi Yochanan and Reish Lakish, second-generation Amoraim of Israel, argue what these nicknames represent. Rabbi Yochanan says they are לְשׁוֹן אוּמּוֹת, language of the gentile nations. Reish Lakish says they are לָשׁוֹן שֶׁבָּדוּ לָהֶם חֲכָמִים לִהְיוֹת נוֹדֵר בּוֹ, language devised by the Sages for the purpose of taking vows.

Attestations of Leshon Umot

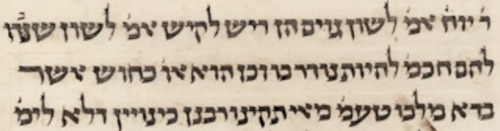

Our printed Vilna text has לשון אומות and I’d favor that reading. We have two further attestations to that formulation in Yerushalmi. In Yerushalmi Nedarim 1:2, we have Reish Lakish (rather than Rabbi Yochanan) explain לְשׁוֹן אוּמּוֹת הוּא. And, in Yerushalmi Nazir 1:2, again we have a flip. Rabbi Yochanan says לְשׁוֹנוֹת שֶׁבֵּירְרוּ לָהֶן רִאשׁוֹנִים אֵין רְשׁוּת לְבִירְייָה לְהוֹסִיף עֲלֵיהֶן. Note “shebireru, that they selected,” with a resh rather than the similar daled of “shebadu” which we have, and explain, in Bavli. Meanwhile, Reish Lakish says לְשׁוֹן אוּמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם הוּא, it is the language of the nations of the world.

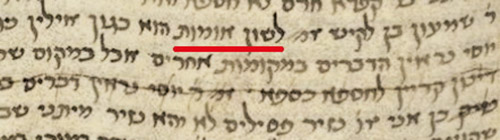

While the Vilna Shas has אומות in all five instances on 10a, I have seen several texts of Nedarim 10a with גוים in place of אומות. Aside from the Venice printing, among manuscripts there is Munich 95, Vatican 110, and others with גוים, while so far I haven’t seen a manuscript with אומות.

So too in Nedarim 3a, when the Talmudic Narrator discusses the idea, the manuscripts I’ve seen have לשון גוים and even the Vilna Shas has לשון נכרים. Also in Ran and Tosafot on Nedarim 2a, the term they use is לשון נכרים, with לשון גוים in the Bomberg Venice printing.

Could לשון אומות be the result of Christian censors, who replaced many purportedly offensive terms—thus נכרים replacing גוים? Perhaps, but I don’t think so. I haven’t fully traced it or checked all the manuscripts, but Leiden, the only complete manuscript of Yerushalmi, indeed has לשון אומות. And we’ll see another reason I believe אומות is original.

Why These Foreign Terms?

Both Ran and Tosafot (2a) wonder at the choice of these particular foreign language terms, assuming a kinuy is לשון נכרים. After all, a neder is effective when made in any language, so long as you intend it and understand what you are saying. Tosafot cites the Ri that these foreign language close-approximations to the Hebrew word will work even if one doesn’t understand them. Ran cites Rabbi Yehuda ben Chasdai that not only regular proper foreign language is acceptable, but even these words from foreign languages which are corruptions of Hebrew words will work.

I would propose an alternative. Rather than leshon umot with a shuruk (vowel), the phrase should be לְשׁוֹן אוֹמוֹת, leshon omot with a cholam (vowel). Consulting Jastrow for a definition, אוֹמָאָה is “the act of administering an oath, swearing, imprecation.” See Targum Yerushalmi on Vayikra 5:1 and 5:4 where אוֹמָאָה and מוֹמָתָא translate אָלָ֔ה and שְׁבֻעָ֖ה.

The words Konam and konach aren’t language from nations, but language of imprecation. People are reluctant and uncomfortable doing so, and so they invent alternative words or phrases to accomplish or hint to it. Thus, in English, to say that Hashem should condemn something to damnation, we have “Gosh darn it,” or as Yosemite Sam is fond of saying, “Dagnabbit.”

The linguistic term for this is a taboo deformation. We even encounter this in Shir Hashirim, where the same pasuk occurs in 2:7 and 3:5. הִשְׁבַּ֨עְתִּי אֶתְכֶ֜ם בְּנ֤וֹת יְרוּשָׁלִַ֙ם֙ בִּצְבָא֔וֹת א֖וֹ בְּאַיְל֣וֹת הַשָּׂדֶ֑ה אִם־תָּעִ֧ירוּ ׀ וְֽאִם־תְּעֽוֹרְר֛וּ אֶת־הָאַהֲבָ֖ה עַ֥ד שֶׁתֶּחְפָּֽץ, “She adjures the daughters of Yerushalayim by gazelles or by hinds of the field.” But rather than gazelles, “Tzevakot” refers to the Lord of Hosts, and rather than hinds, “Ayalot hasadeh” is a kinuy for Keil Shakai.

Taboo deformations often employ linguistic transformations such as dissimilation (where phonemes are replaced with similar phonemes) and metathesis (where letters switch position). In Yerushalmi Nazir, Reish Lakish’s example is כְּגוֹן אִילֵּין נֵיװַתָּאֵי דִּינוּן קַרֵייָן לְחַסְפָּא כַסְפָּא, like those Nabateans who instead of ḥaspa (clay shard) say khaspa (silver).

To argue against my suggestion, note Reish Lakish’s invocation of Nabateans. Further, Rabbi Yossi (an Amora) responds with “this is well and good in other places, but in a place where they call a nazir a nazik, would we indeed say that a nazir who is a psilos (a Greek term meaning having a speech impediment, like Amos who called Yitzchak “Yischak”) wouldn’t be nazir? (See Korban HaEidah about girsa though.) This focus on locale might indicate specifically gentile languages. However, it needn’t be. Rather, It could restrict imprecation language to that which has been widely adopted, such that it has local meaning2.

Practically Speaking

The practical difference between Rabbi Yochanan and Reish Lakish, then, is whether the terms listed in the Mishna are a closed or open class. In linguistics, an example of a closed class (until very recently) would be pronouns, e.g. “he, she, it” and so on. An open class would be verbs, where new ones, e.g. tweet or Google, are being introduced all the time. Resh Lakish would say that if I, or perhaps people generally, would say “Behold I am a shnazir,” it would work.

How would we rule? Should neder/nazir be an open or closed class? Generally, except for about three cases, we rule like Rabbi Yochanan over his student Reish Lakish3. This might be a mere description and mnemonic of how the other Sages ruled, or it could be causative: דברי הרב ודברי התלמיד דברי מי שומעין. Here we also have a reversal of their respective positions between Bavli and Yerushulami. And even if we typically rule like Bavli, would we say Yerushalmi is more familiar with who said what amongst their own Sages?

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Sort of. I’d argue that the first Mishna isn’t concerned with yadot, perhaps aligning with Shmuel. Rather, taking kinuy in its expansive form, it encompasses synonyms. So מוּדְּרַנִי מִמָּךְ literally has the word neder as its root, which synonyms include מוּפְרְשַׁנִי מִמָּךְ מְרוּחֲקַנִי מִמָּךְ. And שֶׁאֲנִי אוֹכֵל לָךְ is what he’s literally vowing against, while שֶׁאֲנִי טוֹעֵם לָךְ doesn’t mean literal tasting, but is a synonym for eating.

2 Alternatively, it could be a reflection on Rabbi Yochanan’s position. In this Yerushalmi, he says it’s Chazal-invented language and no one can innovate. Rabbi Yossi might say that if it is indeed local language, of course it would still work.

3 See Eruvin 36a-b, where Rava lists the three cases, and Tosafot ad loc, who asks why certain other cases are listed. See also Rav Schachter’s discussion, https://tinyurl.com/yc47svby, at the 30 minute mark, where he says this is how they voted.