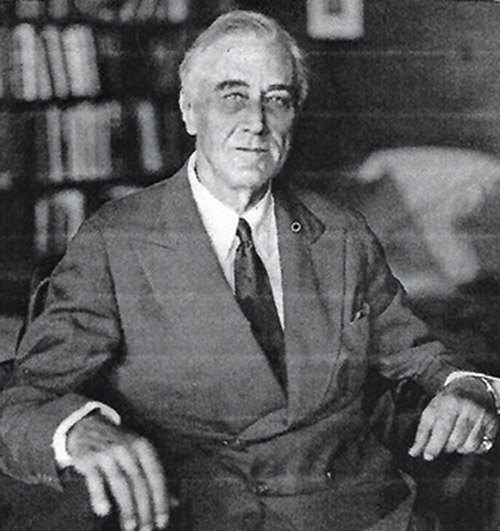

In the first two installments we covered the attempts made by the US Government to increase the Jewish immigration without much success; conferences in Evian and Bermuda, which resulted in no improvements; and the effect of Roosevelt’s health on his decision making.

Ed Flynn, a trusted friend since 1928, and the Democratic boss of the Bronx, wrote in his memoirs, after spending a night at the White House, that he found the president unnervingly disengaged. He wrote of his apparent “lack of interest in the problems facing him,” and of how he now lacked “the power to make decisions.”

Why all these comments about FDR’s health? I could write pages further describing his deteriorating health and how the White House kept it a deep, dark secret. What connection is there between the Jewish Refugee problem and FDR’s health? There is very much of a connection.

FDR’s extremely poor health, peaking in the critical year 1944, when there still existed the hope of rescuing hundreds of thousands of Jews, particularly from Hungary, affected his ability to make decisions. The Normandy invasion, the ending of the war and planning for a United Nations organization to be established after the war, were his main focus. Also on his mind was the coming election and whether he should run for a fourth term.

Everything else was an irritant. FDR’s mind did not follow a straight line, but hopped from suggestion to suggestion. He depended on himself more than others, trying out contradictory ideas, until they came together in a way he found convincing, or at least helpful. General Dwight Eisenhower called him “almost an egomaniac in his belief of his own wisdom.”

The pending invasion and the question of his fourth term followed him everywhere. But other questions, such as the urgency the Nazi mass murders of Jews had lent to the Zionist project for Palestine, had been looked at distantly sympathetically, but not so sympathetically as to campaign for an open-door policy for Palestine. When a boatload of Refugees (the M/S St. Louis) was turned away by officials he had appointed, he looked the other way rather than leave the impression that a fight against Fascism would be a fight on behalf of Jews.

On March 8, Roosevelt met with Rabbis Stephen Wise and Abba Hillel Silver, who wanted him to declare support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. He led them to believe he was fully behind them, but would not be able to say so directly until the war was won. Next day at a cabinet meeting he took up the Arab cause, fully aware that some members of the cabinet were more worried about Middle Eastern oil than the survival of refugees. VP Henry Wallace, who had been present at both meetings, wrote in his diary about FDR, “He looks in one direction and rows in the other with utmost skill.”

On March 21, Roosevelt issued his bluntest statement to date regarding the Jewish Refugee problem. “The wholesale extermination of the Jews of Europe goes on unabated every hour. That these innocent people, who have already survived a decade of Hitler’s fury, should perish on the very eve of triumph over barbarism, which their persecution symbolizes, would be a major tragedy.” These words may now sound inadequate, but they marked a notable rising of consciousness on his part.

At the Yalta conference with Churchill and Stalin, Roosevelt expressed a self-assigned mission to smooth the way for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Remarking that he considered himself a Zionist, he asked Stalin whether he was a Zionist. Stalin replied that he was in principle but “recognized the difficulty.” Stalin wondered what gift FDR would give to the Saudi king, whom he was going to meet in a few days. FDR answered with a smile, “The six million American Jews.”

When he did meet with King Ibn Saud, FDR asked him what could be done for the Jews of Europe, and Ibn Saud replied, “Give the Jews and their descendants the choicest lands and homes of the Germans who oppressed them.” He added, “Arabs would rather die than yield their land to Jews.” Later, aboard his ship, Admiral Leahy said to FDR, “The king sure told you.” And when questioned what he meant, Leahy replied, “If you put anymore kikes into Palestine, he is going to kill them.” FDR laughed.

So what was FDR? He certainly was not a Zionist as he claimed to be to Stalin, any more so than Stalin was a Zionist. I wonder what FDR would have replied if questioned as to his definition of Zionism. Jews, Holocaust, Palestine were never in the forefront of his mind, but rather it was an annoyance to be dealt with as a last resort. He dealt with them by talking out of both sides of his mouth—sometimes at the same time. FDR did help the Jews on a very, very limited scale, but only through back channels in order to avoid upsetting his state department, which was against everything that spelled “immigration of Jews.”

He did have some Jewish friends, such as Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, and his treasury secretary and neighbor in the Hudson Valley, Henry Morgenthau Jr. to whom he once admitted his skill at keeping people guessing, not excluding himself, saying “You know I am a juggler, and I never let my left hand know what my right hand does.”

Morgenthau was a product of generations of German Jews, teachers, businessmen, shochtim and rabbis. But he was discreet about his Jewishness, stayed away from synagogues and Jewish Country Clubs. He was also hesitant about Zionism and keenly aware of the prejudices of the day. He wanted to be thought of not as a Jew but as “100 percent American.” In other words, FDR was not surrounded by friends who would or could influence his thinking about the Jewish problem.

When Stephen Wise’s request to the White House in 1943 for a meeting with FDR was turned down, everyone looked forward to the coming Anglo-American Bermuda Conference. For 12 days the delegates stayed at the luxurious Horizons plantation, built in 1760. No Jews would be heard at the conference. Any specific reference to “Jews” was strictly prohibited because of fears that the Allies would object to any “marked preference” for any “particular race or faith.” The delegates were also warned that the Roosevelt administration had no power “to relax or rescind” immigration laws (ignoring the fact that the US had yet to even fill its legal quotas). As to the possibility that Germany might release a sizable number of refugees of its own accord, again, the delegates rejected the proposal for fear that Hitler might “send a large number of picked agents” into Allied territory, or because the Allies lacked the ships to accommodate a sizable exodus of Jews. No one pointed out that a good number of ships that carried supplies eastward across the Atlantic were actually empty on their return to the US. Proposal after proposal was rejected or put off pending future discussion. A proposal to house refugees in North Africa, after it made its way to the White House, was declared by FDR as “extremely unwise.” At the end of the conference only a one-page bulletin was released to the press saying that the delegates would make confidential suggestions to their governments.

The US State Department took weeks, even months, to deal with issues, or simply to answer correspondence. Why then, was Roosevelt not shocked into creative action? How was it that he seemed incapable of confronting the crux of the problem, the millions of Jews held hostage by the Nazi regime? These questions will remain unanswered forever.

Contrary to Winston Churchill, who was an active and vocal supporter of Jewish causes, and the Jewish homeland, FDR did his best to avoid the problem whenever he could not reject it outright.

By Norbert Strauss

Norbert Strauss is a Teaneck resident and has been a volunteer at Englewood Hospital for the past 30 years. He was general traffic manager and group VP at Philipp Brothers Inc., retiring in 1985. Prior to Englewood Hospital he was also a volunteer at the American Committee for Shaare Zedek Hospital for over 30 years, serving as treasurer and director. He frequently speaks to groups to relay his family’s escape from Nazi Germany in 1941. He has eight grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren.