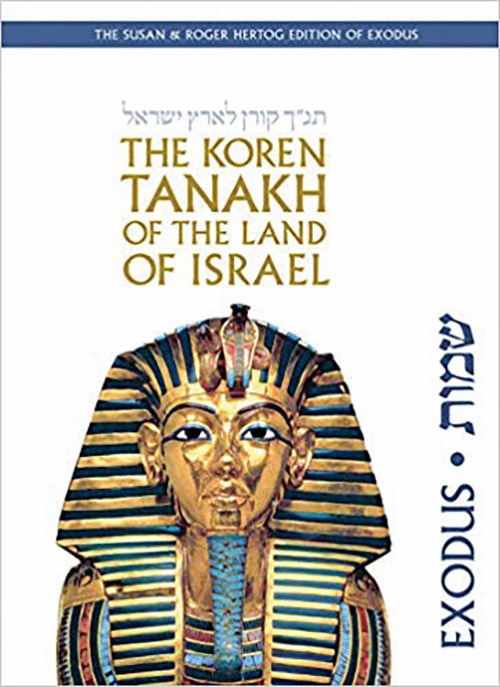

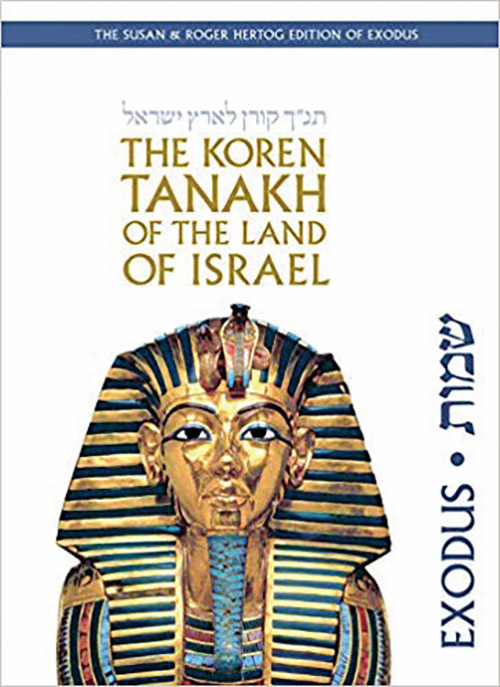

Reviewing: “The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Exodus,” edited by David Arnovitz; English translation by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks. Koren Publishers Jerusalem; 2020. Hebrew, English. Hardcover. 327 pages. ISBN-13: 978-9657760338.

When it comes to an understanding of a subject, context is vital. If someone lacks context, their ability to understand is severely limited. For example, the late Professor Yaakov Elman of Yeshiva University produced a series of studies that considered the impact of Persian culture on the Babylonian Talmud (Bavli). Elman created the scholarly field known as Talmudo-Iranica, which seeks to understand the Bavli in its Middle-Persian context. Anyone who studies the Bavli and wants to understand the bigger picture of the text and context will indeed find Elman’s writings an invaluable reference.

As we start reading the book of Shemot (Exodus) this week, even the experienced reader may lack significant context. For a reader to truly understand and appreciate the narratives here, they need to understand the social and political realities in which they occurred in ancient Egypt. In “The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Exodus,” editor-in-chief David Arnovitz has created an utterly extraordinary work that brilliantly explains the stories in the context of the milieu in which they took place. This commentary does a superlative job of exploring and explaining the Egyptian context of the stories and narratives here.

Arnovitz and his team of 10 academic contributors have expertise in Egyptology, Assyriology, plants, animals, geology, ancient Near East, Tabernacle, and priestly garments biblical scholarship and biblical Israel. Moreover, here he has laid out explanations based on the following eight categories: archaeology, Near East, language, flora and fauna, Egyptology, Mishkan, geography, and Halacha. The result is such that the reader is provided with a much deeper and more meaningful understanding of what occurred in ancient Egypt.

The authors bring to light fascinating revelations within Sefer Shemot, and their explanations bring to light countless new insights to the text via their use of modern scholarly research, ancient Egyptian inscriptions, and archaeological finds, all in order to explore the Egyptian context of Sefer Shemot.

In the 21st-century, when many legal realities match what the Torah says, it is easy to lose appreciation for how revolutionary a legal system the Torah is. To which the authors compare it to prior legal systems, they show that many of the Torah’s laws revolutionized concepts of workers’ rights, slaves’ rights, care for the poor and resident alien, women’s rights and much more.

A few of the many insights the authors bring include:

The story of the midwives Shifra and Puah mimic many practices Egyptian midwives did. Understanding these customs helps explain the Torah’s depiction of Shifra and Puah.

God tells Moshe that the ground he is on is holy ground and to remove his shoes. The concept of a space that is holy was common throughout the ancient Near East, where any place in which a god was believed to be present was deemed holy. When Moshe heard God’s description of the area as holy ground, he would have understood this to be an indication of God’s presence.

The Egyptian workweek was 10 days long. Workers could then request time off to participate in a religious ritual or holiday. When the Jews asked Pharaoh for a three-day holiday, this made perfect sense to him.

When it comes to the 10 plagues, some have tried to show that they were far from miraculous and attempt to give scientific explanations for them. The editors show that each of the 10 plagues was explicitly directed toward Pharaoh, and then the entire episode was explicitly directed to him based on his own set of beliefs.

For example, the plague of darkness was particularly terrifying to the Egyptians. The ancient Egyptian fear of chaos must be read into this plague. In the eyes of the ancient Egyptians, the fact that the sun did not rise meant that the sun god failed to cross the netherworld, and chaos prevailed. That would have been one of the most frightening and disturbing thoughts ancient Egyptian could have.

The book reveals a lot, but there is still a lot to be answered. As with all that, there is still no direct evidence from within Egypt, or in the Sinai Peninsula, that testifies to an Israelite sojourn in the desert. The editors note several plausible explanations for the lack of evidence.

Countless biblical commentaries explore myriad aspects of the biblical text. Nevertheless, this volume is singularly unique in that it is the first to bring these topics to the general audience. These topics were, for the most part, unknown until now and offer a radically new view into the biblical texts.

The Chumash was a radical and revolutionary text in its time that, in essence, told the ancient world to go jump in the lake. “The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Exodus” eloquently and brilliantly shows how radical and revolutionary a work the Torah truly is.

Ben Rothke lives in Passaic.