“Life is full of choices,” we often hear. The truth is, however, most of us set out on a rather mundane life journey, differing little from our parents or other caretakers in our life goals, traditions and practices. Certainly this is a generality that applies to the everyday decisions that we make, if not the major ones in our lives. But every so often we run across someone who is the exception to this rule, who undergoes a noteworthy transformation, a metamorphosis of massive proportions during their lives. One such individual was Henry C. Litchfield, a man who married a cousin of mine during the 1960s. If you had met Henry Litchfield during the last years of his life, you would have been struck by several things about him. How tall and handsome a man he was would have been the first thing. His chasidic garb would have been the second; with his long, reddish beard, lengthy black coat and friendly smile, he would strike you most as an ultra-religious Jewish man of larger-than-life size, one among many on 47th Street in Manhattan. But Henry’s life was unique in many ways. He had not traveled that far geographically from the place of his birth, but culturally, religiously and socially, he had lived a life far more complex and diverse than few others of his experience.

Henry stood 6 feet, three inches tall, a handsome, blond, fine figure of a man. Born in New York City in 1932, the only son of a wealthy Jewish doctor who had parlayed an early advanced incubator he invented into a large fortune. Henry was brought home from the hospital to a well-appointed Fifth Avenue nursery where he was nurtured by nannies and, ultimately, prepared for the fine silver-spoon life into which he was born.

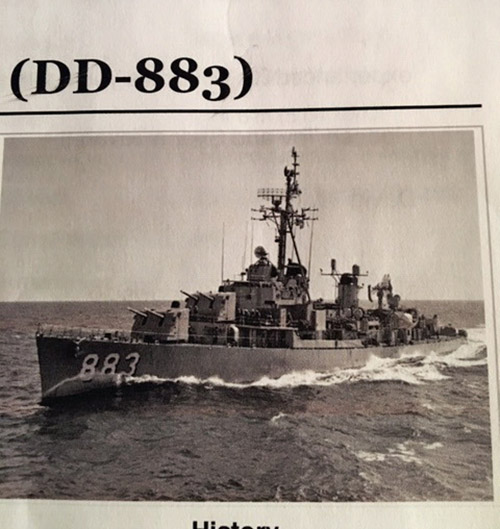

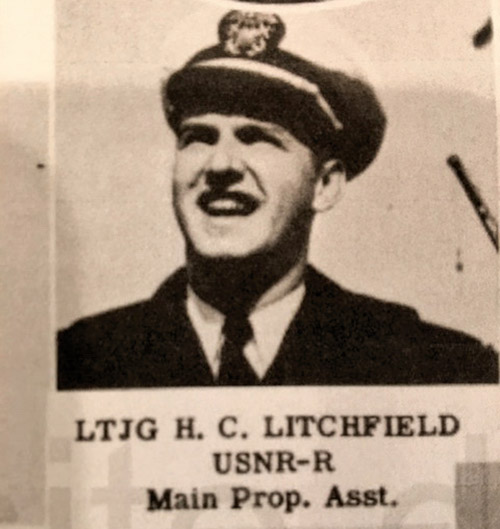

Henry’s home wasn’t a particularly spiritual one; the family considered themselves Reform Jews, but any kind of regular ritual was absent. Henry studied at prep schools as a youngster and showed no particular interest in academics at an early age. With his size and above-average coordination, Henry excelled at sports and was a natural leader on the fields of play. He was a champion squash and tennis player. He graduated high school, attended Washington and Lee University in Virginia and graduated without any particular sense of direction. At school he majored in English and was a member of the school debating team. His father would have loved for Henry to follow in his medical footsteps, but Henry had no interest in doing so. He spent his post-graduate days seeking a brief military career in the US Navy where he served with distinction as a peacetime naval officer, cruising the Mediterranean in the mid-1950s on a naval destroyer. After mustering out of the navy, he began to dabble in business, but politics became his first true love. Henry became fascinated by the early 1960s with the political stance of the fledging Conservative party of New York, the latter’s right-of-center politics reflected by such luminaries as William F. Buckley and Bill Rusher, publisher of the National Review. In New York, the policies espoused by Henry’s political friends were initially considered beyond the pale of the dominant, liberal ideology of the day. (In time, many of the tenets endorsed by the Conservative party became mainstream during the Reagan-Bush years of Republican dominance.)

As he reached his early 30s, Henry, still unmarried, underwent something of a religious awakening. On one occasion, Henry wandered into an Orthodox synagogue during Shacharit services and was fascinated with the congregants who were wearing their tefillin as they prayed. He asked several men what was happening and they took the time to explain to him their rituals. After that chance meeting, Henry decided to explore more deeply the life of observance. Inspired by local Orthodox rabbis in Manhattan, Henry began to study Jewish traditions and lore and, as a result, he became more and more eager to live a traditional Jewish life. He met his future wife, Rita, when a mutual friend thought they would be “perfect for each other,” and they hit it off immediately. Rita came from a Modern Orthodox Jewish home in Manhattan, her parents both born in Europe, her father a scholarly businessman, her mother a homemaker. There was a significant age difference between Henry and Rita (over 10 years), but her maturity and self-confidence closed any gap and they shortly fell in love.

Once his engagement to Rita was announced, the respective families met and it became clear that Henry’s soon-to-be “new” family and Henry’s parents were not exactly on the same page. They were courteous toward each other, but did not warmly welcome each other. Henry was faced with deciding whether to take the plunge and live according to the Orthodox tenets Rita was committed to or remain true to his parents’ less observant lifestyle. It took about two years, but gradually Henry saw no alternative but to throw himself fully into the Orthodox Jewish world. This meant observing all the tenets of the Torah, keeping the Sabbath (no more driving on Saturdays or the Jewish holidays), keeping kosher (no more eating “real” Chinese food, his favorite) and studying the holy books for insights into proper religious practice.

During the early stages of their marriage, Henry and Rita enjoyed traveling together, including frequent trips to the Catskills where they spent time participatingin outdoor activities in the countryside. On one notable occasion, Henry showed off his equestrian skills during an outing with Rita’s teenaged cousin. On the trail, Henry, ever the competitor, challenged her cousin to race him to the stables, about a half-mile away. The young fellow was a novice at horseback riding and in a matter of seconds, Henry’s horse leaped ahead at a gallop, leaving the cousin to hold on for dear life as his mount vainly sought to keep pace. When the cousin finally reached the finish line minutes after Henry did, Henry praised him for not falling off!

Though he didn’t necessarily want his new life to lead to rupturing his old relationships, inevitably it had that effect over time. Always one to think through the consequences of his thoughts and actions, Henry ultimately saw the Modern Orthodox practices of his wife’s family as being inadequate. His personal, religious goals went beyond conventional Modern Orthodoxy, and he gravitated over time to the world of the so-called Ultra-Orthodox, of chasidus.

Interestingly, his move to the right, religiously, didn’t change his politics at all. In fact, Henry would preach to his friends and family that realistically all Orthodox Jews should be the supporters of the platform espoused by the Conservative Party of that time: respect for law and order, family values etc. In that regard, Henry was way ahead of his time, as many Orthodox Jews were to leave the liberal Democratic ranks as they matured and vote for Republican candidates (Reagan and the Bushes, father and son) who supported the now-mainstream views of the National Review and the neocons.

By 1987, Henry and Rita, now the parents of 11 children, had moved to the insular chasidic community of Monsey, New York, from the Upper East Side. Soon Henry became further immersed in the chasidic lifestyle around him. The former US Navy Lieutenant JG became almost unrecognizable to his family and erstwhile naval officer comrades in both dress and behavior, wearing the garb of a chasid and letting his reddish beard and peyot grow wild. Henry’s grandfather had been a respected and successful real estate developer, but his family opposed Henry’s continuing in that business given his lifestyle changes. Faced with that opposition, he essentially walked away from the family business, endeavoring to invest what money he possessed, first in his own real estate business and, after little success, in a jewelry business. Throughout, Henry strove to keep smiling as he lived out his new life. With many children and a wife to care for, he had little choice.

Fate was ultimately unkind to Henry. Soon after his 57th birthday, Henry became ill and had to be hospitalized. He developed a septic infection that did not respond to antibiotic treatment. He passed away surrounded by his family. The shock of his sudden death at such a young age remains to this day with his family and friends. And what of Henry’s legacy, his offspring numbering in the dozens? His widow lives a quiet life in Brooklyn. His children and grandchildren? Some are chasidic in practice, some consider themselves Modern Orthodox and one or two are not observant. Henry, always an independent thinker, would undoubtedly have been unhappy that his offspring did not all follow the Torah-observant traditions he adopted during his complicated life; he would nevertheless have taken some pride in the fact that they are all, in the opinion of many, upright, decent human beings.

But as always, unanswered questions remain. Who knows how his children’s lives would have evolved had Henry lived longer, long enough for his uni

que journey from Sutton Place to Monsey, and from nonobservance of Jewish traditions to chasidus, to have assured the legacy he had hoped to leave behind?

By Joseph Rotenberg