In the midst of the worldwide concern over the “Bad Deal” concocted by the Obama Administration with the mullahs of Iran, it occurred to me that had fate ruled otherwise, the entire issue of Iranian possession of nuclear armaments might possibly have been resolved a long time ago in a much less contentious manner. Accompany me back to New York City for a couple of minutes and I’ll explain what I mean.

It was October of 1959, fall had just begun and the High Holidays and Sukkot were over. The members of the Stern family were preparing for the onset of Shabbat, the table was set with all the familiar finery and the mother of the house was lighting the candles as the four children scurried about in last-second dashes to complete their tasks. The only figure missing from this scene was the father of the house. Of course, he really wasn’t missing. As was his usual practice, he had left the ground floor apartment moments before to attend Friday night services at the shul conveniently located around the corner on 103rd Street, off Riverside Drive. Soon after his departure, each of the five other members of his family spread out in the modest living room, each of his three daughters choosing a different corner of the room armed with a book or magazine that she eagerly began to read. The only boy in the room was a 9-year-old son who was playing with his toy soldiers on the carpet that covered part of the living room floor. His mother sat in a sofa chair opposite her children, trying to read the local paper without falling asleep. This scene continued unchanged for about 35 minutes.

At last a key turned in the front door lock.

“Daddy’s home!” shouted the boy as he jumped up from the floor, knocking over most of his toy soldiers.

To everyone’s surprise, it was not only Daddy who came down the hall into the living room. Walking behind him was a slightly built young man with a friendly face, dark complexioned. Upon his head he wore a large multi-colored skullcap. The men paused in the middle of the room:

“Folks, I want to introduce you to Eshagh Shaouli. We met in shul this evening. He was sitting by himself in the back. He just arrived in America on Tuesday from Iran. He’s an exchange student at Columbia College. He doesn’t know anyone in New York and so I invited him to have Shabbat dinner with us tonight.”

The father introduced his children one by one to Mr. Shaouli who greeted each in turn. Finally, he was introduced to Mrs. Stern who welcomed him warmly. The Sterns’ home was always open to strangers and they actually looked forward to hosting such visitors who might need a place to stay or a meal to eat. But this young man from Iran, ancient Persia, the land of Purim, of Esther, Mordechai and Achashverosh, was obviously someone special. After the introductions, Mr. Stern left Eshagh’s side to prepare the silver cups for the recitation of the Kiddush blessings. Soon the family, along with their exotic guest, stood alongside their seats as Stern intoned the ancient prayers. Upon the completion of the Kiddush, each sipped the wine that Stern carefully doled out. The Shabbat meal then began in earnest. As course followed course, the children watched their guest carefully, fully expecting him to reveal something of his foreign background and customs. But Eshagh simply smiled at his hosts, accepting their generosity in gracious silence. At last, the young boy asked Eshagh why and how he had come to America:

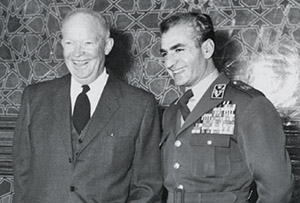

Eshagh responded promptly and the story he proceeded to tell everyone was special indeed. Eshagh explained that the Shah of Iran who had come to power in his country with the assistance of the U.S. government, was among the first world leaders to undertake a new program outlined by President Eisenhower. It was called “Atoms for Peace,” and envisioned the proliferation of peaceful nuclear capability throughout the world. The Shah was eager to obtain these capabilities, perhaps as a buffer against the then Soviet Union with its extensive border with Iran. As a first step in his nuclear quest, the Shah scoured Iran to collect the best minds in the country to study nuclear physics, mostly abroad. Ultimately he chose 10 of the most qualified Iranians to spearhead this program, of whom, quite incredibly, seven were Jews! Eshagh was the last selected and he was assigned to begin his studies in the Physics Department at Columbia College in New York. He had arrived in New York only three days earlier.

The Sterns were impressed by Eshagh’s story. He continued to fill in some of the personal blanks:

“My father died several years ago, but my mother, two sisters and three brothers all still living in Tehran. There is a large Jewish population there and we are treated pretty well by the government.”

As the meal neared its end, Eshagh listened carefully to Mr. Stern singing his regular Shabbat zemirot with occasional assistance from his son. When the singing ended, Stern couldn’t resist asking Eshagh if he had any traditional Persian Shabbat songs he might like to sing for them:

“Of course, we have many songs. I will sing you one from the Tehilim, King David’s song from Psalm 23.”

Eshagh began to intone the words of the famous psalm, Mizmor LeDavid, chanting the ancient words in a pleasant voice. The tune was somewhat dissonant to the ears of these American, Ashkenazi Jews, rising and falling in unexpected ways, highlighted by a loud choral part that surprised the listeners. Shutting one’s eyes, however, a person could easily have been transported to far-away Persia, as the tune and Eshagh’s accent conjured up images of caravans, divans and harems.

Abruptly the song was at an end, and the Sterns each in turn complimented Eshagh for his vocal efforts. He thanked them and said:

“It must sound strange to your ears, the music of Iran, but we like to sing and ‘get together’ like you do in this country.”

At the conclusion of dinner, Eshagh said farewell to his new friends and left for the windy walk to his Columbia dorm some 15 blocks north. He arrived safely and went to bed, pleased to have made such good friends and to have been welcomed into such a warm home so soon after arriving in America. In the weeks and months ahead, Eshagh became a regular guest at the Stern’s home. In time they “adopted” him and included him in their family gatherings and celebrations. As the months turned into years, the Sterns helped Eshagh bring his siblings over to New York from Tehran, allowing his sisters to live in their home for extended periods of time until they could find satisfactory work and accommodations of their own. The Sterns even arranged for Eshagh’s brother, David, to have delicate open heart surgery in New Jersey; the operation ultimately saved his life. In time the Sterns became substitute American grandparents for the Iranian Shaouli clan, who treated the Sterns with respect and love.

In the midst of this modern American story of gemilat chesed toward newcomers, important world and local events were taking place. First U.S. nuclear policy changed rather abruptly. In place of “Atoms for Peace,” the focus in Washington shifted to the nonproliferation of nuclear weaponry, with the frightening realization that the peaceful development of nuclear capability could easily be converted or directed to warlike uses. The Shah’s development program looked shakier and shakier. Aside from that, on a local level, as Eshagh became more and more integrated into American life, he began to consider changing his major at Columbia. Finally, in late 1960, the Iranian government informed him they were ending the program and terminating subsidization of his nuclear physics studies. Eshagh announced his decision to study economics instead. The University and the Sterns together assisted him in continuing his studies at Columbia. Eshagh went on to an illustrious career as the treasurer of a major American banking institution where he supervised investments in the Far East.

As for Iran, the moment in time for the peaceful development of Iranian nuclear power passed into history just like that, barely noticed and with the slightest of fanfare. Imagine how different things could have been. Where would we be today exactly had Iran in fact developed peaceful nuclear capability in 1960? Would a later regime change (as occurred in 1979) have delivered nuclear weaponry into the hands of a group of terror-promoting fanatics as we fear might now occur? Or would a concerned United States have intervened more effectively to prevent such regime change as took place, obviating the very debate we are having today? Whatever one might say about these varying scenarios, the irony stands: Iranian Jews, like Eshagh Shaouli, were a critical support element—really, at the heart—of the Shah’s nuclear plans in the 1950s. Today, Jews worldwide are staunch opponents of Iran’s nuclear aspirations and the declared targets of Iran’s nuclear objectives. With world peace and Israel’s security at issue, let’s hope the current nuclear plans suffer the same fate as those authored by the Shah over a half century ago.

By Joseph Rotenberg