The historical clash between Greek culture and that of the Jews is an ancient one. It is not merely a clash of ideas, but at points in time, bloody confrontations between nation-states and armies have taken place at various locations in the eastern Mediterranean. Students of the Greek and Jewish peoples are quite familiar with battles and confrontations between Hellenists and Jewish populations in Judea and wider Israel, as well as in Alexandria in Egypt, in the first and second centuries before the Common Era.

In its boldest contrast, the monotheistic Jews stood in stark contrast to the pantheistic Greeks; the latter were said to adopt a philosophy of life that stressed the veneration of the body as well as of the mind, holding the pursuit of virtue to be the highest ideal. The Jews, too, were a nation of philosophers in the truest sense: they loved knowledge and its acquisition. Their monotheism led them to different conclusions as to what was important in life. They appreciated at some level maintaining fitness and health, but only to the extent that it aided them in the fulfillment of their religious obligations. In ancient times, the Greek and the Jew could agree on very few things, in particular, what is known as the Golden Mean: “Do unto others as you would have them do to you.” But despite the similar love of ideas and knowledge, the two peoples for the most part challenged each other for centuries in both word and deed, with disastrous consequences for both.

As has occurred often enough in the past, both the Greeks and Jews ultimately fell under the sway of Rome. They did so in different ways, but at least initially Rome respected both cultures and peoples. The Romans craved obedience from their subject peoples. From Greece, the Romans adopted wholesale the Olympian philosophy. From the Jews, the Romans appreciated their respect of law and devotion to principle, as well as the importance of learning. Both peoples ultimately had to forsake their independence as Rome evolved from republican rule to imperial standard. The Greeks morphed into the role of advisers par excellence to the Roman ruling class, while the Jews bristled under the increasingly oppressive Roman thumb. We all know what resulted for the Jews: destruction and diaspora. While the Greek antipathy towards the Jews seemed to fade into the background, even 60 years after the destruction of the Second Temple, the infamous Roman emperor Hadrian (known by his favored nickname Graeculus, “Little Greek”) spent much of his time in Athens and in Asia Minor at the home of his best friend, Antiochus Epiphanes IV, direct descendant of the infamous Antiochus Epiphanes of Chanukah fame.

So we sing every night of Chanukah in our time, 2,300 years after the historical events, in the hymn of Maoz Tzur of “Greeks (who) gathered against me in Hasmonean days, (who) breached the walls of my towers and … defiled all the oils.” The Greeks referred to in the familiar song were the Syrian-Greeks who attempted to Hellenize (impose Greek culture) on Eretz Israel through force.

Not long after the events of Chanukah, Jews and Greeks clashed outside the land of Israel and far from Greece proper in the famous metropolitan area of Alexandria in Egypt. Those Greeks who resided in Alexandria competed with a well-established community of exiled Jews; philosophers and merchants on both sides competed in the marketplaces of goods and ideas. As what was by then an old debate and bone of contention with the Jews, the Greeks supported the concept of a pantheon where gods of many religions were invited to participate on an equal footing. This was anathema to the Jews, who believed in the exclusiveness of the Mosaic god of Sinai and refused

the Greeks’ olive branch. Acrimonious debate led to gruesome bloodletting and intolerance. The growing influence and dominion of Rome quelled the Greco-Jewish wars, but only temporarily.

Over the ensuing decades and centuries, the Romans adopted Greek religion and culture and then, ironically, both Greek and Roman paganism adopted wholesale a once-despised Jewish sect called Chrisitianity, with negative implications for Jews throughout the world.

Which brings us to modern times, particularly, to the last 100 years or so, during which a development so amazing has occurred in Jewish-Greek cultural interactions that literally anything seems possible.

In this connection, it will be instructive if we follow one young American boy, Jake Rabinowitz, as he grew up in New York in the 1950s. His was an Orthodox home, but along with studying Torah and Talmud, he studied secular subjects including Aesop’s Fables and Greek mythology. By the time he reached yeshiva high school in the 1960s, a major portion of his English literature syllabus consisted of Greek myths; detailed knowledge of this material is required.

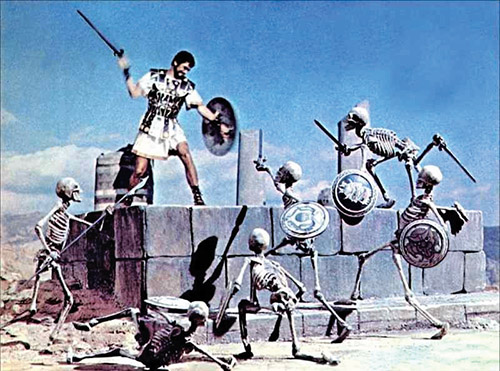

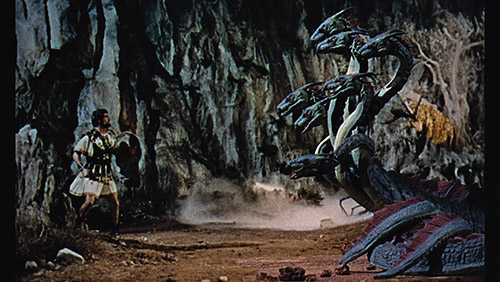

Aside from the regular academic study of Greek culture by devout Jewish teens, during the 1950s and 1960s, Americans at large were being exposed during these years to lavish, colorful Hollywood productions of epic Greek tales and characters. On any given weekend, Jews could enjoy dramatizations of “Ulysses” (1954), “Hercules” (1958), “Jason and the Argonauts” (1963) and other Greek characters, culminating in the grandiose “Clash of the Titans” (1981). These fantastical productions were largely the result of the efforts of one man, an American Jew named Charles Schneer (1920- 2009), who befriended an award-winning, non-Jewish animator named Ray Harryhausen, the latter providing memorable, lifelike creatures such as the Cyclops, the Hydra and Medusa for Schneer’s studio.

The ironic fact that a Jew (Schneer) was almost single-handedly responsible during his life for the popularization and dissemination of Greek culture and myth through his films should not be lost. Through Schneer’s creative output, after two millennia of conflict, Jews and Greeks have seemingly erased their conflicts.

In the case of Jake Rabinowitz, a final twist to the modern Greco-Jewish thaw took form one eventful day when this young tax attorney working for an entertainment law firm in New York received an urgent phone call from a West Coast accountant. At the other end of the receiver was Fred Shapiro, asking for Rabinowitz’s insight on some tax issues that the IRS had raised concerning a producer-client. The client in question turned out to be none other than Charles Schneer! At that point Schneer was living as an expat in London, but happened to be in New York for production meetings for an upcoming project.

“Can you meet with Charlie tomorrow to discuss his case?” Shapiro asked. Rabinowitz jumped at the chance to actually meet the man who had famously brought the “fighting skeletons” who opposed Jason and the Argonauts to the screen. “I’d be happy to do so! I’ve enjoyed his movies for years!”

The meeting soon took place and Rabinowitz was fortunately able to save Schneer a lot of aggravation, not to mention cash. All Rabinowitz wanted from the producer was a walk-on part in his next production, but the young attorney found that expertise in solving tax problems doesn’t count for much in Hollywood! Among other things, Hellenized Jews don’t shut down production on the Jewish Sabbath, so Rabinowitz’s career as a mythological character essentially ended before it started.

Schneer’s films are still popular decades after this New York Jew brought these Greek fantasies to the silver screen and are certainly enjoyed today by the descendants of the Maccabees. So much for Kulturkampf in the 21st century!

Joseph Rotenberg, a frequent contributor to The Jewish Link, has resided in Teaneck for over 45 years with his wife, Barbara. His first collection of short stories and essays, entitled “Timeless Travels: Tales of Mystery, Intrigue, Humor and Enchantment,” was published in 2018 by Gefen Books and is available online at Amazon.com. He is currently working on a follow-up volume of stories and essays.