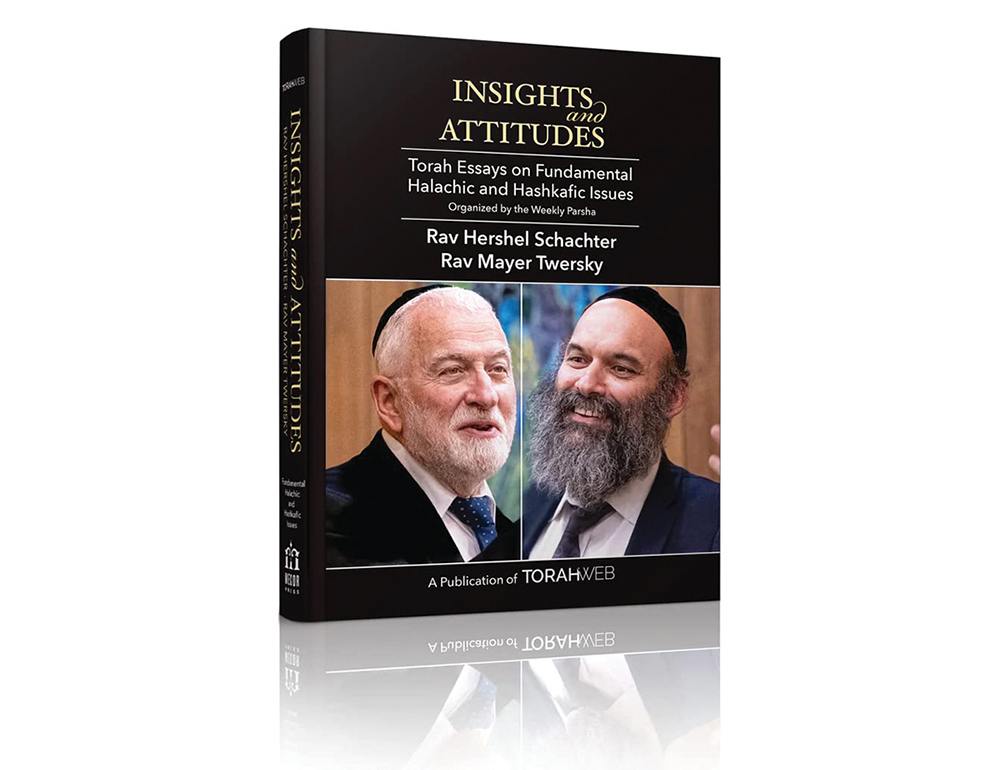

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights and Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles—organized by parsha—by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

The Torah records that the Jewish people entered into a covenant (bris) with God regarding observance of the mitzvos on two occasions. The first bris was at Har Sinai and the second took place in Arvos Moav, just before the passing of Moshe Rabbeinu. We still observe today the takana of Ezra to read the tochacha in Bechukosai soon before Shavuos and the tochacha in Ki Savo soon before Rosh Hashanah (Megillah 31b). These two tochachos represent the text of the two covenants—the one at Har Sinai and the other at Arvos Moav.

Why was there a need for a second covenant? If the bris at Sinai was legally binding, what dimension was added with the bris of Ki Savo?

The Torah gives us the answer in the beginning of parshas Nitzavim (Devarim 29:13-14), where we are told that this second bris is not only binding on the individuals present today, but on all future generations as well. The bris at Sinai, apparently, was only binding on those individuals who were present. Although the Talmud (Shavuos 39a) records a tradition that the souls of all the future generations also participated in maamad Har Sinai, this was only relevant with respect to impressing upon all of those souls the Jewish midah of baishanus (shame), due to the gilui Shechina they encountered; but those souls were not legally bound to adhere to the contractual agreement of the bris.

The concept of a Jewish people only emerged in its fullest state once the Jewish people entered Eretz Yisrael and acquired their own national homeland. For a covenant to be binding on future generations, it must be entered into by a nation, which the future generations will still belong to. The second bris—with the nation—was only begun by Moshe Rabbeinu, and was really completed by Yehoshua bin Nun at Har Gerizim and Har Eival. The principle of arvus (that all Jews are held responsible for each other because they all constitute one entity) only came into effect after the declaration of the brachos and kelalos at Har Gerizim (Sanhedrin 43b).

Rambam records several mitzvos (commentary to Bechoros 4:3; see Nefesh HaRav, page 80) which only apply in Eretz Yisrael because—as he explains—the main concept of klal Yisrael applies only to those Jews actually living in Eretz Yisrael. After our entering Eretz

Yisrael, the fact that Jews all over the world relate to Eretz Yisrael as their national homeland makes us all halachically considered one nation with respect to arvus, and, more significantly, with respect to the binding force of the second bris. Today, we are still obligated in mitzvos—not because of the first bris (at Sinai), but rather because of the second bris.

It is interesting to note that all the pesukim in parshas Bechukosai appear in the plural—as opposed to the text of the bris in Ki Savo—where all of the pesukim appear in the singular. The Gaon of Vilna points out—based on a passage in the Talmud (Menachos 65b)—that when a parsha appears twice, once in the singular and once in the plural, the parsha in the singular is addressing all of klal Yisrael as one entity, whereas the one in the plural is addressing each and every individual. In our case as well, the tochacha in Bechukosai is the text of the bris made with each individual Jew; the tochacha in Ki Savo is the text of the bris made with klal Yisrael as one entity—one nation.

According to the halacha, the one and only people who constitute a goy—nation are the Jewish people (Bava Basra 10b). We are the only people who have a divinely recognized national homeland. The other nations of the world, strictly speaking, are only mishpachos—families. The difference between a “goy” and a “mishpacha” is that a mishpacha consists of various individuals who relate to one another in a certain fashion. The term “goy” derives from the word “geviya—body.” In the Jewish nation (goy), we all are considered to be one body (see Eretz HaTzvi, pages 118-120).

The Talmud Yerushalmi (Nedarim 9:4) comments on the prohibition against taking revenge, that just as if one accidentally cut his left hand with a knife held in his right hand, he would not react by slapping his right hand with his left to take revenge, since both hands are part of the same organism; so too, it doesn’t make sense for one Jew to take revenge against another Jew, for all Jews join together to constitute one “goy”—one body.63

This is the idea behind arvus—which is a principle formulated in parshas Nitzavim in the last pasuk dealing with the second bris—which was begun by Moshe Rabbeinu and completed by Yehoshua at Har Gerizim. As long as there is still one Jew somewhere in the world who hasn’t yet heard the shofar, I haven’t yet completely fulfilled my mitzvah of shofar, and, therefore, I’m considered as one who is (still) obligated in (mechuyav badavar) the mitzvah of shofar, so I am still able to blow for another person who hasn’t heard shofar.

This halachic distinction between the Jewish people and other nations also explains the phenomenon that we often witness: when one Jew acts in an inappropriate fashion, the non-Jewish world will often indict all Jews, while if one Frenchman acts improperly, no one will think of condemning the entire French nation. The reason for this distinction is that the entire Jewish people is truly one body (goy), while the other nationalities are merely mishpachos.

Referring to the non-Jewish nations and to a single non-Jew as a “goy” is really an (halachically) imprecise colloquialism. Many gedolim felt that it is not correct to recite the text of the bracha—every morning—as “shelo asani goy,” since brachos and tefillos ought not to be recited in colloquial Hebrew. Many substituted instead, “shelo asani nochri” (Nefesh HaRav, page 107). The second bris at Arvos Moav made the Jewish people unique.

אתה אחד ושמך אחד ומי כעמך ישראל גוי אחד בארץ

“You are one and your name is one, and who is like your nation, Yisrael, one nation in the land.”

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.

62 See “It’s in Our Genes,” above in this volume, parshas Ki Savo, page 267.

63 Editor: See “Chillul Hashem,” above in this volume, parshas Emor, page 165 where Rav Schachter also discusses this point.