Medical science at the beginning of the 20th century was heavily focused on bacteriology and infectious diseases; the study of cancer at that time was a scientific backwater. Thus, if one were to ask who was a major scientific superstar in cancer research at the time, not many names would come to mind. But, certainly, the leading contender for that role would be Johannes (OK, Johannes Andres Grib) Fibiger. As I say that name, you may say, “Who?” As do I. But recently I came across an article by Paul Stolley about this man, the recipient of the 1926 Nobel Prize in Medicine, the first ever awarded for a cancer discovery. And I will tell you why we never heard of him—because his research for which he won the Nobel Prize subsequently turned out to be wrong! Let us tell the story below.

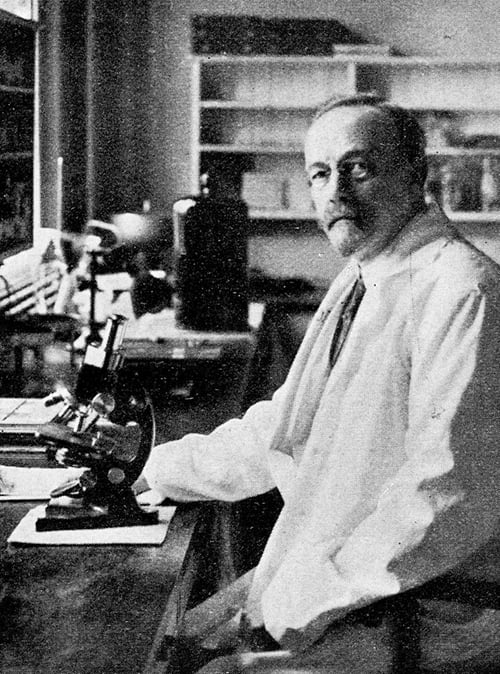

Johannes Fibiger was a Dane, born in 1867 in Silkeborg, Denmark. He studied medicine at the University of Copenhagen, where he also later obtained a PhD in bacteriology. He studied in Berlin as well with Emil von Behring, the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Medicine, and with Robert Koch, a later winner of the Nobel Prize for his work on tuberculosis. In 1900, Fibiger was appointed professor and director of pathologic anatomy at the University of Copenhagen, a post he held until his death in 1928. Much of his research focused on diphtheria and bacteriology but we, of course, are interested in his cancer work.

In 1907, Fibiger was studying wild rats and found stomach papillomas in three of them. He dissected these tumors and found nematodes (worms) in them and decided that the worms were the cause of the tumors. He did a literature search and found a paper published in 1878 that noted that this particular worm was found in the common cockroach, which he decided was the intermediate host for the worms. He named the worms spiroptera neoplastica.

He then started examining wild rats; he trapped and examined over 1,000 of them but found no further tumors. In parallel, he found 61 rats in an infested sugar refinery of which 40 had nematodes in their stomachs; seven of them also had growths that Fibiger called gastric cancers. He also found and trapped cockroaches at this refinery, many of whom carried the nematodes.

He next devised an experiment in which nematode-infested cockroaches were fed to mice and the mice were followed to see if they developed cancers. In 1919, he reported that he could successfully produce stomach cancer in mice in this way (published in the Journal of Cancer Research). He reported a proportional relationship between the number of worms carried by the cockroaches and the incidence rate of the tumors that developed. He hypothesized that a similar parasite might be responsible for gastric cancer in humans.

There were those who questioned the validity of his work. It was argued that these were not carcinomas but rather some form of hyperplasia, a benign growth, that was induced. (Indeed, dear reader, papillomas are not malignant.) Also, his critics complained that he did not state how many of the rats with stomach cancer did not have spiroptera neoplastica present.

Fibiger’s research was considered so exciting because the prevailing theory was that there was some kind of organism responsible for the genesis of cancer. The discovery of a parasite as a possible etiologic factor was just in tune with that model. The citation for his Nobel Prize stated that his discovery started a new era in cancer research and that cancer had been experimentally produced beyond all doubt. The work and the awarding of the Nobel Prize did have a significant stimulatory effect on further cancer experimentation.

Fibiger died in January 1928 from colon cancer. In 1935, a pathologist questioned the work and suggested that the tumors were really metaplasia (a benign condition) due to vitamin A deficiency that had been exacerbated by the nematodes. Rats fed a full and healthy diet did not develop these tumors. In 1952, an American group attempted to repeat Fibiger’s experiments. They fed one group of rats with adequate vitamin A and another group with vitamin A-deficient food and then exposed them to the nematodes. Only the vitamin A-deficient rats developed lesions and they proved to be benign tumors. Fibiger had apparently fed his rats white bread and water; the scientists in 1952 interviewed the bakers from Fibiger’s time and ascertained that there would not have been eggs or milk in this bread.

The problem with Fibiger’s research was the absence of control groups. Stolley takes him to task for this. But we really should have a kinder view and see his work in the context of its time—control groups were not a standard practice in the scientific world at that time. And as we judge errors or mistakes in scientific research at the present time, at least we can say that Fibiger’s work was honest and not fraudulent, and it was without plagiarism.

Alfred I. Neugut, MD, PhD, is a medical oncologist and cancer epidemiologist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York Presbyterian and Mailman School of Public Health in New York. Email: ain1@columbia.edu.

This article is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, and does not constitute medical or other professional advice. Always seek the advice of your qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment.