There is no corner of human experience devoid of religious meaning. We stand before God in our grand moments of achievement as well as in the hushed silence of our own frailty. Every living organism, including humans, must remove the waste that is a byproduct of homeostasis and metabolism. Instead of viewing this experience as shameful, we utilize it to appreciate the wonder of the human body. The blessing of “asher yatzar,” recited after visiting a washroom, articulates the majesty of the human body and the miracles of its proper functioning.

In a similar vein, Parashat Re’eh lists the prohibition against defacing a human body. The Torah specifically warns against bodily disfigurement in the aftermath of tragedy, but a broader ban applies to any unnecessary defacement of the human form. Every human being possesses divine dignity and must have their noble image preserved. As a people chosen to model the dignity of religion, Jews are especially commanded to preserve the excellence of the human body, by maintaining its pristine and divinely crafted form.

Body Image Crisis

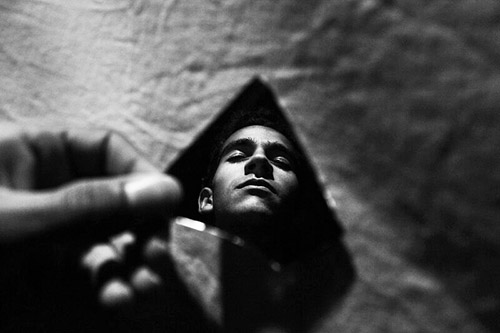

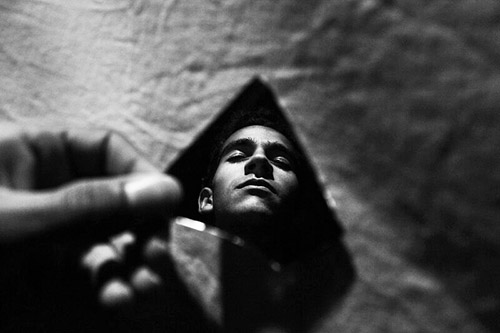

In the modern era, we are suffering a body image crisis. The rates of dysmorphia, or an unhealthy attitude about our body, is rising—especially among younger people. These unhealthy feelings can lead to psychological suffering, social insecurity and, sadly, to self-injury, such as cutting oneself and other forms of bodily mutilation.

Several cultural factors have contributed to this crisis. Modern society has become more fitness-oriented, and this has improved both our physical health and our well-being. However, the fitness revolution has also idealized a “toned and sculpted” body type, which may be difficult to attain and even more challenging to sustain. Our culture has convinced us that a more attractive body will land a dream job, increase our social popularity or secure an ideal partner. We have set a very high standard, and when we fail to reach it, we feel “lower” about our bodies and about ourselves.

Objectification of human beings and, in particular, of women, has exacerbated the body image crisis. Using human bodies to sell products or exploiting women as objects for male gratification, demeans human dignity and degrades the human body into an instrument for attention and attraction.

Social media has deepened the crisis by providing a steady flow of “perfectly” photoshopped celebrities. This endless stream of flawlessly looking people causes ordinary people to feel insecure about their “inferior” appearance.

What does Judaism have to say about body image and how are modern religious norms affecting this crisis?

Fusion of Body and Spirit

Judaism does not divide between the soul and the body. We possess an eternal soul, which will long outlast our bodies, which wither with the passing of time. Yet, despite the stark differences between our fading body and our eternal soul, Judaism avoids casting the body as sinful or shameful while glorifying the soul as noble and virtuous.

The great sage Hillel, while once attending to personal hygiene, informed his students that he was involved in a religious duty! He explained that the human anatomy is a divine masterpiece, and its proper upkeep and maintenance would therefore be considered a mitzvah or an act of chesed.

Maimonides remarked that physical health is a religious imperative, or as he referred to it “the preferred way of God.” In his view, a medically infirm person cannot hope to properly and clearly understand the ways of God.

A Delicate Union

Rabbi Moshe Isserles, the 16th-century Polish articulator of Ashkenazi Halacha, argued that the blessing of “asher yatzar” doesn’t merely address the general splendor of a human body. In particular, it showcases the indivisible bond between body and soul. These two parts of our identity are so vastly different, yet God bonded them into one inseparable unit. Physical well-being impacts spiritual growth, and spiritual prosperity contributes to physical health. The two elements of the human condition are so incongruous, yet they feel indistinguishable. Though we are composed of two dissimilar elements, during our lifetime they are one, and we are one. This divine miracle is extolled in the blessing of “asher yatzar.”

Judaism doesn’t bifurcate affairs of the soul and affairs of the body. As our bodies house our souls, the dignity of our body must be preserved and we are instructed to avoid any bodily mutilation or disfiguration. Healthy body image and careful attention to personal hygiene and physical fitness are part of religious orientation and attitude.

Religious Norms and Diminished Body Image

Ironically, modern religious norms can sometimes exacerbate our body image crisis. Modern culture has become both oversexualized and obsessed with physical appearances. Celebrities are not famous for significant accomplishments, but simply because they are attractive, or at least are presented to us as more attractive. This cultural obsession with physical beauty has produced a crass culture of voyeurism. The surging popularity of reality shows over the past 30 years, highlights our unhealthy addiction to gawking at attractive people.

This powerful wave of exhibitionism and insatiable obsession with physical beauty has caused an understandable recoil in religious circles. In our attempts to protect ourselves from this cultural deluge we sometimes overreact and swing too far away from balanced messages. Do religious people sometimes pay too little attention to hygiene, fitness and positive body image, because we unfairly suspect these values as irreligious or even dangerous to our religious virtue? Have we forgotten that reasonable attention to fitness and personal hygiene is part of religious identity?

An acute problem concerning healthy body image sometimes stems from the way we message about tzniut or personal modesty. tzniut is not purely a women’s issue and extends far beyond the matter of covering our bodies with appropriate clothing. tzniut is a state of mind incumbent on every person—both male and female. It is an internal consciousness that draws from the recognition that we constantly stand before God and therefore we should not draw exaggerated attention to ourselves. tzniut-consciousness also stems from humility, not evaluating ourselves as better than others or worthy of public attention or interest. tzniut-conduct stretches across a broad range of behavioral issues, one vital expression of which is the manner in which we dress. Strict adherence to the norms of modest dress, must be accompanied by a clear understanding of the basis of tzniut.

By shrinking the broad value of tzniut solely into a myopic issue of how women dress, we sometimes signal unhealthy messages about body image. Staunch demands about covering the body, without a broader illustration of the meaning of tzniut, can inaccurately imply that the human body is inherently sinful or immoral. Additionally, by highlighting the way we cover our body without proper “tzniut-framing,” we may be generating too much attention about physical appearances. If we place too much attention on simply covering up without articulating the basis of tzniut, we may, ironically, be coaching children to equate self-worth with physical appearance.

We are exquisite creatures of God—in our full and whole being!

The writer is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He has smicha and a BA in computer science from Yeshiva University as well as a masters degree in English literature from the City University of New York.