The Mishna on Kiddushin 74a deals with people prohibited to marry into the Israelite congregation, e.g. a mamzer. The Tanna Kamma says all such prohibited people may nevertheless marry one another. Rabbi Yehuda, a fifth-generation Tanna, prohibits this. Rabbi Eliezer says that those with definite flawed lineage may marry one another (such as a mamzer to a Giveonite), but those with uncertain flawed lineage marry someone with either definite or uncertain flawed lineage. Finally, a list of those with uncertain lineage: שְׁתוּקִי, אֲסוּפִי, וְכוּתִי.

It would be strange for Rabbi Eliezer (ben Hyrcanus), third-generation Tanna, to be listed after fifth-generation Rabbi Yehuda, to argue with him. Indeed, the Masoret Hashas, a marginal commentary in the Vilna Shas, authored first by Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz and with subsequent comments in brackets by Rabbi Yishayahu Pick, argues in a bracketed comment that this should be Rabbi Eleazar (ben Shamua), a fifth-generation Tanna. I agree. The parallel sugya in Yevamot 37a has רבי אלעזר, and it works with later gemaras, as Tosafot discuss. Read it inside—Rabbi Pick could get his own Jewish Link column. I’ll still write my own column, with similar evidence but slightly divergent conclusions.

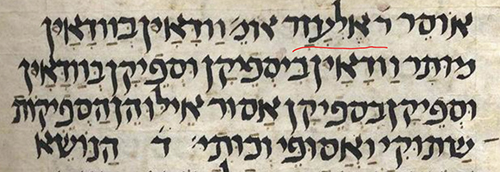

Manuscripts for Kiddushin differ on the Eliezer/Eleazar question. But the Kaufmann manuscript, Guadalajara Talmud printing, and the Oxford 367 and Chabad 1701 manuscripts all have Eleazar in the Mishna, thus matching the Yevamot parallel. However, Rabbi Eleazar or Rabbi Eliezer will appear elsewhere in the Gemara, as well as in the parallel Tosefta, so there is much conflicting evidence. I would land on Rabbi Eleazar ben Shamua.

One of those with “doubtful” lineage was the Samaritan. Presumably, the Samaritan community didn’t heed this prohibition of marrying other Samaritans, or else there wouldn’t be a modern-day Samaritan community. Rather, the halacha addresses one or two Samaritans who wished to integrate with the Jewish community. Concerns about the original Samaritan conversion process, public policy conditions or practical ramifications about their keeping/rejection of Oral Law (including laws of marriage and divorce) could complicate their status.

Rabbi Eleazar’s Motivation

Our sugya begins on Kiddushin 75a with a quote from a brayta (Tosefta Kiddushin 5:2): וְכֵן רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אוֹמֵר: כּוּתִי לֹא יִשָּׂא כּוּתִית. This full text is אלו הן הספיקות שתוקי ואסופי וכותי וכן היה ר’ אליעזר אומר ממזר לא ישא את [הממזרת וכותי] לא ישא את [הכותית] וכן שתוקי ואסופי כיוצא בהן. This matches the position of Rabbi Eleazar or Eliezer of the Mishna, that the doubtful shouldn’t intermarry with the certain, so our identification should remain consistent—Rabbi Eleazar . It’s interesting when sugyot are based on a quote from the parallel Tosefta when the Mishna should have sufficed.

Amoraim try to understand Rabbi Eleazar’s position. What is problematic/safek about a Samaritan’s status? Rav Yosef suggests a public policy approach – they are of convert status but cannot marry a mamzer because they seem like other Jews, and this would confuse people as to the halacha. This is attacked by Abaye. Rav Dimi came from Israel and stated that Rabbi Eleazar is aligned with Rabbi Akiva, who is aligned with Rabbi Yishmael. The Gemara expands upon with which of Rabbi Akiva’s positions, and with which of Rabbi Yishmael’s positions this aligns, but notes a basic incompatibility between Sages and positions and therefore rejects the approach. Finally, when Rabin came from Israel, he indirectly cited Rabbi Yochanan (though the citation chain might be different), that there’s a three-way Tannaitic dispute between fourth-generation Rabbi Yishmael (Samaritans were historically insincere converts), fourth-generation Rabbi Akiva (sincere converts but differed regarding levirate marriage), and a third unattributed position (sincere converts but not well versed in details of commandments).

Identifying Yeish Omerim

Regarding the third, unattributed position, יש אומרים, two rabbis try to identify him. There is Rashi, who writes ויש אומרים – היינו רבי אליעזר. And, in the immediately following Gemara, the question is posed מַאן יֵשׁ אוֹמְרִים? Rav Iddi bar Avin identifies him as Rabbi Eliezer, based on a Tosefta (Pesachim 2:2) presenting a three-way dispute. The Tanna Kamma maintains that Samaritan matzah is permitted (not chametz) and one can fulfill his obligation of matzah with it. Rabbi Eliezer forbids, because they’re not experts in the details of commandments. Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel disagrees, for in those mitzvot that they do keep, they are more scrupulous than your typical Jew.

We should wonder why Rashi would explain what Rav Iddi bar Avin himself will explain. Perhaps Rashi is trying to explain to which of the three positions (Rabbi Yishmael, Rabbi Akiva, Yeish Omerim) Rabbi Eleazar aligns, rather than suggesting an identification. Also, we don’t really know whether Rashi’s girsa, both above and below, is either Rabbi Eleazar or Rabbi Eliezer consistently. That is the real question: are we dealing with the same Tanna as before?

The Guadalajara and Venice Talmud printings have אלעזר, as does Munich 95, Vatican 110, and Oxford: Heb. b. 10/25–26 manuscripts. Meanwhile the Constantinople printing and Chabad 1701 manuscript match our Vilna text of אליער. Note that Rabbi Iddi bar Avin’s statement also appears in our Vilna printing of Gittin 10a referring to Rabbi Eleazar, and in Chullin 4a as ר”א, thus unclear. In Berachot 47a, that position is simply אמר מר. We could examine manuscript variants in Gittin and Chullin to assemble more evidence.

We should also consider the companions of this ר”א in our disambiguation attempt. In the Tosefta, he appears alongside Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, where two Tannaim bore this name. The former was a second-generation Tanna, while the latter was a Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel of Usha, in the fifth-generation. I’d guess the fifth-generation one, which would recommend fifth-generation Rabbi Eleazar, over third-generation Rabbi Eliezer. Still, he could respond to/reject an chronologically earlier view. And, in Ravin’s account, the unnamed Yeish Omerim, who Rav Iddi bar Avin says is ר”א, appears right after fourth-generation Tannaim, Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Yishmael. This might indicate either a third or fifth-generation figure. I believe the Gemara works best with a different Tanna here, so I would land on Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyracnus.

Finally, Rabbi Pick points us to a Tosafot in Bava Batra 93b. There, Rav Chisda identified the Yeish Omerim of a brayta as Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel. Tosafot are bothered with this, since in Horayot 13b, fifth-generation Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Natan unsuccessfully conspire to depose Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel II from being Nasi. They are first exiled from the beit midrash, then are readmitted, but still penalized by not having the halacha cited in their names. Rabbi Meir is cited as Acheirim and Rabbi Natan as Yeish Omerim. Yet in Bava Batra 93b, Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel is the Yeish Omerim, and regarding a brayta on 36b, Rav Chisda says Yeish Omerim is Rabbi Acha. Further, in a brayta on 15b, Rabbi Natan himself argues with a Yeish Omerim! We can add our own sugya to this, though it’s in an Amoraic statement. It seems that this identification is not an absolute rule. Rather, when they referred to Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Natan anonymously, these are the respective terms they used. That doesn’t mean that every Acheirim and Yeish Omerim are these two Tannaim.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 The few manuscripts don’t carry Rabbi Eleazar forward, but the Guadalajara printing correctly does.