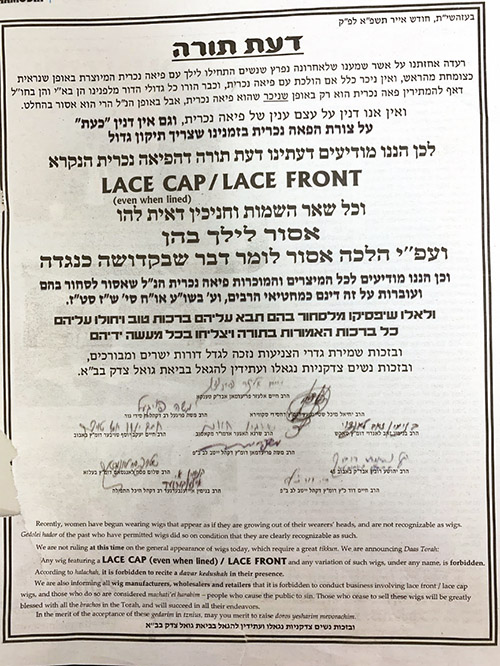

Over the past month or so, readers of a number of prominent Orthodox Jewish publications have noted a series of ads restricting or discouraging the use of certain kinds of women’s head coverings, including a publicized teshuva declaring lace front or lace-topped wigs as inappropriate for use by married women.

These are wigs that have natural-looking roots by having the wig hair attached to a thin lace top, and are among many different types of hair coverings that married women use, in addition to falls, bands, full sheitels, scarves, hats and fascinators.

Not everyone in the northern New Jersey community has been supportive of placing restrictions on head coverings, and one local rav has stated that anything that discourages a woman from observing a mitzvah in a way that is comfortable for her is not advisable. In recent days, other rabbanim in the region have added their voices in agreement.

Rabbi Yaakov Neuburger, mara d’atra of Congregation Beth Abraham in Bergenfield, who also serves as a rosh yeshiva at Yeshiva University, spoke extensively on the background and halachic sources of the mitzvah of kisui rosh (head coverings) for women at a recent Shabbat shiur. Approximately 100 women attended the afternoon event during Shabbat Korach.

The sheitel, or in fact any head covering, addresses two concerns of the Torah. Rabbi Neuburger demonstrated that the two mitzvot are separate with virtually little overlap. The Gemara in Ketubot 72a records that the Torah communicates the mitzvah that married women wear a headcovering by presupposing it in the narrative of the procedure that addresses a family suffering the accusations of infidelity. The extent of this biblical mitzvah does sustain ambiguities regarding the size of the covering and the place (such as a marketplace or a private courtyard) that necessitates it.

On the contrary, the Gemara in Berachot 24a describes the requirements of modesty that is expressed through dress and headcover. In relation to this mitzvah, Rabbi Neuburger shared the 20th-century debate on whether hair covering is in any way socially dependent. He discussed how this affects the parameters regarding covering one’s head in one’s own home and nearby men who are davening or learning.

Pursuing the approach that one should adopt halachically acceptable approaches that ease the observance of the mitzvah, he advocated adopting Rav Moshe Feinstein’s allowance of a tefach of hair to be visible. A tefach is an unprescribed amount that one can see in a single glance, so women don’t necessarily have to be concerned if a small amount of hair escapes cover. Rav Neuburger added that he wanted to emphasize that anything that restricts women (or anyone) from observing a mitzvah in a halachically acceptable fashion, should be discouraged. “This is especially true for a mitzvah whose observance carries many challenges and whose observance has enjoyed a major comeback that is still fresh in our memories,” he said.

While Rabbi Neuburger noted the highly regarded stature of the poskim who authored the lace top prohibition, he found it particularly disturbing that the natural look of a lace front sheitel should be objectionable “because it looks natural,” or because it makes a married woman’s hair look attractive. He noted that the mitzvah is probably a chok and its reason is largely hidden from us, and was never designed to make a woman’s hair look less attractive, and that a natural-looking sheitel is not immodest.

Rather, he presented the approach of Rabbi Saul Berman, longtime professor at Stern College for Women, who outlines the association of head covering throughout biblical and rabbinic texts, beginning with the kohen in the Temple, with moments of heightened mindfulness and awareness of Hashem’s embrace, thus adding fuel to the belief that head coverings are a mark of an elevated responsibility, opportunity and status. Accordingly, the wide variety available of head coverings for women, from scarves to hats and wigs of all types and elegance, fulfill the mitzvah. Perhaps the existence of personal choice, personal expression and simply comfort have strengthened the resurgence of the mitzvah that had been largely lost in many communities in the 19th and 20th century.

Finally, Rabbi Neuburger noted his concern with such a chumra (stringency) taking hold when it is unnecessary, and took at least half a dozen questions to clarify the halachic parameters.

By Elizabeth Kratz