Tisha B’Av, the most tragic day in the Jewish calendar, is a day full of sadness. We observe the strictest traditions of personal and collective mourning, sit on the floor and read lamentations, remove all of the finer dressings from our synagogues and even do not put on tefillin in the morning—to show our unworthiness to wear the item described in the Gemara Berachot as pe’er, or a symbol of our glory as God’s chosen people. On Tisha B’Av, the day when an entire generation, including Moshe and Aharon, were sentenced to die in the wilderness, when two temples were destroyed, we cannot wear pe’er because it is difficult to see ourselves as God’s chosen people.

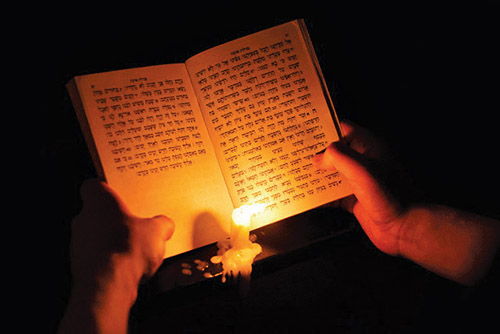

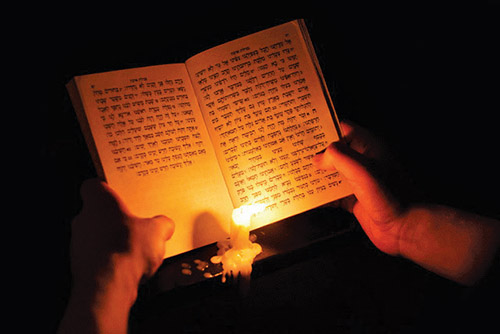

In stark contrast to the hopelessness of nearly every other aspect of the observance of Tisha B’Av, the Torah and haftarah readings, while sad, are actually quite hopeful. Beginning with the shlosha d’paranuta, the three haftarot read during the three weeks of bein hametzarim, through the readings from Va’etchanan and Yirmiyahu read on Tisha B’Av itself, the theme is pretty much the same: the Jewish people as a whole will sin, will be exiled from their land, will do teshuva, and Hashem will return them to Eretz Yisrael. This is far from the message of the kinot, and of Yirmiyahu’s lamentations immediately after the Churban in the form of Megillat Eicha. Furthermore, Chazal have forbidden learning Torah on Tisha B’Av except for these and other similarly themed portions. Clearly there is a deeper message here. What can we learn from the juxtaposition of the stringent, almost hopeless, mourning traditions of the fast day and the significantly more hopeful Torah portions on the same day?

The Meshech Chochma, toward the end of Sefer Bamidbar, teaches a powerful lesson on the tochacha, the scary admonition of what happens to the Jewish people when they stray from the path of Torah. God warns Moshe, in very similar terms as the Torah reading on Tisha B’Av morning, that when the Jews settle and begin to forget the miracles that God performed for them, He will have no choice but to remind them of His presence. The crux of the sin, a word that appears many times in Bechukotai but less in Va’etchanan, is “keri,” or approaching our relationship with God with too much casualness.

One can certainly understand the seriousness of the sin of relating to God with “keri”—Hashem had taken our ancestors out of Egypt b’zroa netuya— with an outstreched arm, performing tremendous miracles to free them from slavery, transport them through the desert, and bring them to the Land of Israel. How could anyone of the following generations even think of sinning, of performing avoda zara, eating meat of non-kosher animals, realizing how much of a hand God personally had in their parents’ lives? Only through keri, through ignoring the past miracles and relating to Hashem in the most casual of ways, could they sink to that low.

Rav Meir Simcha HaKohen of Dvinsk, a leader of Ashkenazic Jewry in the late 19th century and author of the Meshech Chochma, took the message of the tochacha and brought it forward by over 3,000 years with the following eye-opening perspective:

All of Jewish history since the destruction of the second Beit Hamikdash can be seen as an unfortunate and repetitive cycle. Two thousand years ago, the Jewish people were exiled from our land because of our sins, because we did not properly respect God nor fellow Jews. Ever since then, we have wandered from land to land, with the same pattern repeating itself. The Jews, kicked out of their home away from home, would settle in a new land, initially cautious as they built their separate communities and Torah centers. However, as time went on, the Jews became successful in their new environment and began to want to “fit in” to their new host culture, leaving Torah values behind in the process. In a not-so-subtle jab at a newly formed liberal movement that had begun to form in his later years, Rav Simcha Meir HaKohen predicts that the assimilating Jews will become so distanced from their religion that they will believe that “Berlin is the new Jerusalem.” At that point, he explains, God intervenes to ensure that the Jewish people will never be lost—by causing the host nations to hate us. Anti-semitism, pogroms and inexplicable attacks and violence will prevail, and the assimilating Jews will have no choice but to remember their past and their culture, and run away to a new country before their destruction is ensured. Then, as history has shown, this cycle will repeat again. Why? Because of the sin of relating to God through keri, by not recognizing where the anti-Semitism is coming from and why we’ve deserved it.

This is the lesson of the tochacha, and I believe that it may explain exactly why the theme of the Torah readings around Tisha B’Av are so dialectic—hopeless, yet hopeful. Our history is one series of unfortunate events after another. The Spanish Inquisition, the French Revolution, the Shoah… the list continues. At each juncture, the Jews have become the enemy. It’s at times like that when we must consider our relationship with God and ensure we are not sinning by relating to Him with keri. On Tisha B’Av, as we remember the ancient tragedies that beheld our nation, as well as the more recent ones, and mourn all of the suffering our people have endured for the sin of not appreciating Hashem’s hand in our lives, it is crucial that we think deeply about this concept. Where do I see Hashem in my life? How do I relate to Him, and how often do I recall the miracles that He’s done for my ancestors and for me?

Everyone will have their own unique answer to this question. For some, it may echo the theme that the Meshech Chochma touched on, how many movements of Judaism have disregarded most of the Torah since his time because they don’t feel like specific mitzvot positively affect their spirituality. Our relationship with God should be about more than just our mixed feelings. Disregarding mitzvot because we do not properly understand them could very well constitute keri. For others, it could be a lack of appreciation for the modern-day miracles Hashem has performed in the returning of the Jewish people to Zion and the founding of the State of Israel; many who have a difficult time fitting Jewish sovereignty into their personal vision of Judaism often find it simpler to rally against it, disregarding a crucial chapter in Jewish history, the antithesis and antidote to the tochacha, in the process. Everyone has their own challenges, and their own avoda to work on, and Tisha B’Av, as we review the consequences of relating to Hashem with keri, is the perfect time to look inside and reevaluate our life perspectives and relationship with Hashem.

As much as this is a daunting task, there is a silver lining, which is echoed in the shlosha d’paranuta, as well as in the Torah and haftarah readings on Tisha B’Av itself: God has promised that He will never let us be destroyed. One way or another, we will get through our personal and national challenges, and He will send the geulah. The only question is how will this come about? To quote the well-known idiom, will it be by the carrot or the stick?

In the past few weeks, we’ve seen strife between Jews about control over the Western Wall, a site with minimal intrinsic holiness, and almost immediately afterward, a terrible attack on Har HaBayit leading to the death of two brave Israeli policemen. Perhaps, what we can learn from this is a reminder of the importance of uniting in the face of tragedy and of giving deference to the true holiest site in Judaism. Many American Jews have chosen politics and liberalism over Jewish interests, yet were barred from marching at the LGBT pride parade in Chicago because of thinly-veiled anti-Semitism by the parade’s organizers; perhaps they should re-evaluate who their true friends are? Chazal, on the beginning of Eicha, teach (1:3) that at this time of year (bein hametzarim), when so many tragedies have befallen our nation, there will be increased animosity against the Jewish people. Recent events in 5777 have only proven this ancient teaching to be true.

Anyone truly seeking out God’s hand in their lives can see this idea in an even stronger way, behind the scenes, but only if they try. Let us choose the carrot. Let us recognize Hashem’s hand in our lives and do our best to stop relating to Him with keri. Let us all internalize the miracles that are taking place in our lives every day. May we all merit a fulfillment of Zechariah’s vision (8:19) that this saddest day of the year will become a day of celebration that Hashem has answered our tefillot, Jerusalem has been rebuilt, we are consoled over her 2,000-year mourning and experience salvation from our current strife, and have a complete redemption very, very soon.

By Tzvi Silver/JLNJ Israel

Tzvi Silver, a Teaneck native, has been living in Israel since 2011. He is in his final year of studying electrical engineering at JCT-Machon Lev in Jerusalem, works as an investigator for Israel’s Ministry of Justice and serves as JLNJ and JLBWC’s senior Israel correspondent. He will be drafting into the IDF at the end of the year to serve as an academic officer in his field.