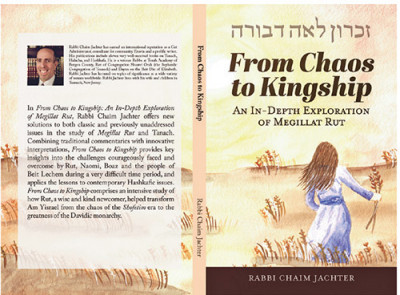

Reviewing: “Megillat Ruth: From Chaos to Kingship,” by Rabbi Chaim Jachter. Kol Torah Publications, ISBN 9798824532852, 168 pages; 2022.

It is always a special kavod to be asked to review a book, to be among the first granted the honor of cracking open a new edition created in the name of Torah scholarship. This time, being asked to review a book by our own Rabbi Chaim Jachter, a regular Jewish Link columnist, was doubly special, because the cover art was painted by a friend, Bergenfield’s own Miriam Kaminetzky, who very often specializes in art made from wedding glass. Her beautiful watercolor art depicts our heroine, the biblical Ruth, collecting sheaves in the fields of Boaz. The sefer, sponsored in the loving memory of Miriam’s mother, Leah Devorah (Linda Mitgang, a”h) was a cause taken up by Miriam and David and their entire family, the extended Mitgang clan. May my review also serve as a zechut for the elevation of Leah Devorah. May her memory be a blessing.

Rabbi Jachter, as a beloved rebbe at Torah Academy of Bergen County, is inspired by his students and thus compiles some of his seforim in a unique way. He uses his students’ expressed insights, which he attributes to the talmidim while thanking them for their contributions. The footnotes in this sefer are rife with familiar Teaneck surnames.

I would be remiss if I did not mention that Rabbi Jachter is a talmid chacham inordinately accessible to his community in many areas, not just at TABC, but also as a community rav of Shaarei Orah Congregation in Teaneck, as a dayan on the Beth Din of Elizabeth, and as a well-known posek for the Teaneck/Bergenfield community eruv and others nationwide. As if that weren’t enough, those who read The Jewish Link every week know that no issue of our newspaper is ever complete without Rabbi Jachter’s column, which almost never addresses the same issue twice and certainly never fails to be both insightful and enlightening.

Rebbetzin Jachter told me that this is the penultimate book that Rabbi Jachter wrote during the pandemic. He used his time in isolation wisely, to finally put together many of his planned projects. I know of no one else so prolific. If any of this sounds familiar to our readers, you may remember that it was just this past January when I reviewed Rabbi Jachter’s previous book about Tanach, on Sefer Daniel. He also published another book since then, quite a bit broader in scope and so detailed, in an area outside my experience that I was relieved to have not been asked to review. This was the well-regarded “Bridging Tradition: Demystifying Differences Between Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews,” published by Koren.

Moving to Megillat Ruth, it’s exciting to spend time with the heroine of our upcoming Shavuot holiday. Surface reading of the text only reveals a shadow about her fascinating journey, so I enjoyed getting to know her and deepened my understanding of her surroundings much better during my reading of this sefer. The book’s construction is linear, generally going through each perek, discussing the major lessons of each section in a clear way. As is his practice, Rabbi Jachter intersperses comments and questions from talmidim, and it gives the sense of a vibrant classroom dynamic. The book is literally filled with nuggets of golden apples encased in silver, as Torah ideas often are. Here I only have space to introduce a few of the novel ideas I encountered.

We are introduced to Ruth with the literal death blow of Elimelech and his two sons, highlighting a very interesting/dangerous system of reward or punishment from Hashem. It is generally a widely held belief that they incurred divine punishment for having left Eretz Yisrael voluntarily, during a famine, possibly in order to not have to give tzedaka. Yet Naomi, Ruth’s mother-in-law, is not subject to the death penalty. Why?

Rabbi Jachter and his talmidim discuss the fact that Naomi was herself not punished for moving outside Eretz Yisrael, even though her husband and sons were subject to an early death. Why is this? It appears that in the first seven perakim of the sefer, Naomi is never described as permanently living, or even sort of living, in Moav. “Rather, pasuk 7 describes the time that she was—or ‘hayeta’—in the fields of Moav. It sounds like she merely existed in Moav, since for Naomi dwelling in Moav was not true living.” (page 33).

Second, everyone knows, generally, that Ruth is the Jewish world’s first convert. It is a matter of much discussion of whether her husband died as a punishment for marrying a non-Jew before she had converted, but again, the prevailing opinion is that her husband died, like his father and brother, for the sin of leaving Eretz Yisrael. It is Ruth’s status and identity as a Moabite princess that places her in such an awkward position with her mother-in-law, the vaunted Naomi, who knows that it will be difficult for them to move back to Israel: They may be shunned, and life will certainly be complicated by the prohibition at that time against Jewish men marrying Moabite women.

That’s why Naomi prevails on both her daughters-in-law to return to their father’s houses, making sure they know and are willing to live Jewish lives if they join Naomi in Beit Lechem. “Naomi sets the model of testing for commitment,” Rabbi Jachter writes. “Those who follow in the path of Ruth and display a commitment to overcome adversity are to be enthusiastically welcomed. However, those unable to make a commitment are better off not joining the fold” (page 44). While one daughter-in-law, Orpah, leaves Naomi to return to her family and avodah zara (idol worship), Ruth declares her loyal intentions and converts to Judaism, returning with Naomi to Beit Lechem. One of the benefits of the sefer is we actually learn quite a bit about the halacha and practice of gerut (conversion) in practice, as well as levirate marriage, by observing the actions and interactions of Naomi, Boaz and Ruth.

There are multiple fascinating interpretations for what happened when Boaz meets Ruth for the first time, but generally it is glossed over that the barley and wheat harvest—a period of three months—actually pass between the time Boaz has a pleasant first conversation with Ruth, and their subsequent meeting “after hours” in the granary, which set into motion the cascade of events leading to their marriage.

“Malbim explains that three months is the time mandated by halacha for a convert to wait before she marries, called havchanah.” (Yevamot 42a, page 74). Rabbi Jachter explains to his talmidim that an excellent example of why a convert should wait to marry is that Ruth needed time to acclimate to her surroundings in Beit Lechem and the Jewish community before marrying. A perfect example: “In pasuk 21 Ruth believed that Boaz wanted her to stay with his young men. Naomi, in pasuk 22, gently corrected Ruth, explaining that Boaz wanted Ruth to stay with his young women” (page 75). Rabbi Jachter also references Rabbi Bachrach, who believes that Boaz was also still mourning his wife at the moment he met Ruth, and as he had lost all 60 of his children in his lifetime, he was not ready for the next step of levirate marriage/yibbum/geula when Naomi and Ruth first returned to Beit Lechem.

My last highlight that really impressed on me a deeper understanding of Megillat Ruth, is Rabbi Jachter’s expounding on the levirate marriage that Boaz undertook. It was not conventional yibbum, not exactly an interaction between Boaz and Ruth as the widow of his brother—she was the widow of his grandson—but one between Boaz and Naomi (his brother’s widow), who had the claim to the land and a “daughter” to marry off. Because Ruth was not Jewish at the time of her marriage to Machlon (page 139), it was actually not she who had a claim to the land that Elimelech had abandoned in Beit Lechem. It was Naomi who would be the relative to whom the property passed. It was Naomi’s field that Boaz could restore to her, and while Naomi’s sons were dead, the only way for Naomi to have a child to pass on the land to, would be for Boaz to have a child with Naomi, or her designee.

According to Rabbi Jachter, this interesting, somewhat chaotic legal situation, which required the Sanhedrin to be present to certify, teaches us quite a bit about halacha and inheritance. In some ways, the chaos and subsequent peace and joy felt following the birth of Naomi’s “grandson” is a metaphor for the birth of the Moshiach, himself a descendent of David HaMelech, and therefore also an ancestor of Boaz and Ruth (page 167).

“Megillat Ruth: From Chaos to Kingship,” is available on Amazon or wherever Torah books are sold.

By Elizabeth Kratz