The Mishnah (Yevamot 20a) lays out three types of prohibited relations: אִיסּוּר עֶרְוָה, אִיסּוּר מִצְוָה, and אִיסּוּר קְדוּשָּׁה, with distinctions as to whether chalitza is required. It defines “issur mitzvah” as relatives one is Biblically permitted to marry but are rabbinically, secondarily prohibited. It defines “issur kedushah” as those to whom there is a Biblical prohibition but marriage would nevertheless be effectuated, e.g. a divorcée to a regular kohen.

Abaye explains the terminology: It is called “issur mitzvah” because of מִצְוָה לִשְׁמוֹעַ דִּבְרֵי חֲכָמִים, it’s a mitzvah to heed the words of the Sages. (We might point to Devarim 17:11, not to deviate from the words that they instruct you.) When a brayta notes that Rabbi Yehuda reverses the terms, Abaye explains that whoever fulfills the Sages’ words is called holy. Now, Rava objects. Is one who violates the Sage’s word merely not holy? He is wicked! Rather, Rava said, “Sanctify yourself with what is permitted to you.”

Rava likely agrees with Abaye regarding “issur mitzvah” and only disagrees with Abaye’s attempted creative kvetch, making קְדוּשָּׁה still have to do with heeding Sages. Let’s explore the principle, and Rava’s relation to it, across Talmud.

Rava and Abaye employ this principle in Chullin 106b, about washing hands before consuming regular, non-terumah, food. There, Rav Idi bar Avin I (third and fourth-generation Amora) cites Rav Yitzchak bar Ashiyan (second-generation) that the rabbinic decree for everyone is due to kohanim’s concerns when eating terumah, and furthermore, because of “mitzvah.” What mitzvah? Again, Abaye (fourth-generation) explains מִצְוָה לִשְׁמוֹעַ דִּבְרֵי חֲכָמִים. Rava (fourth-generation) has a cute riff on it, saying it is rather a mitzvah to listen to the words of Rabbi Eleazar ben Arach, a third-generation Tanna.

That is, Rabbi Eleazar ben Arach cites a verse in Vayikra 15:11 about a zav not having washed his hands in water and therefore transmitting tum’ah, and says, “from here, the Sages based [סָמְכוּ] hand-washing from the Torah.” Rava, in conversation with his third-generation teacher, Rav Nachman (bar Yitzchak), explores how this interpretation from Rabbi Eleazar ben Arach works. (Depending on the girsa, it’s either ambiguous who explains, or it’s Rav Nachman.) Yet, shortly thereafter, we see that Rav Nachman maintains that those who wash their hands for fruits are haughty, while Rava maintains that it is no obligation or precept, but merely optional. This is difficult to square with these two Amoraim working on the mechanics of the interpretation. Perhaps we distinguish between washing for bread vs. fruit—see Chagiga 18b, where this distinction is made while citing Rav Nachman’s haughtiness statement, but the derasha might work equally for both. We might alternatively resolve this by understanding the meaning of Rava’s, and Rabbi Eleazar ben Arach’s, statement.

When Rava said מִצְוָה לִשְׁמֹעַ דִּבְרֵי ר”א בֶּן עֵרֶךְ we might understand as objecting to Abaye and declaring that it’s actually Biblical, as per that Tanna’s derasha (Rashi). Alternatively, he’s pointing to a specific Tanna whose words we can follow, but that Tanna is pointing out Scriptural hint for what remains a rabbinic enactment, as that verse is used in Niddah 43a for other purposes (Tosafot). Indeed, the words מכאן סמכו חכמים implies a hint, an asmachta, rather than a true derasha. Finally, perhaps Rava’s clever retort was meant to undermine it as a minority opinion, rather Sages’ words more generally, which would hold weight. They still take pains to understand the derasha as a mark of proper scholarship.

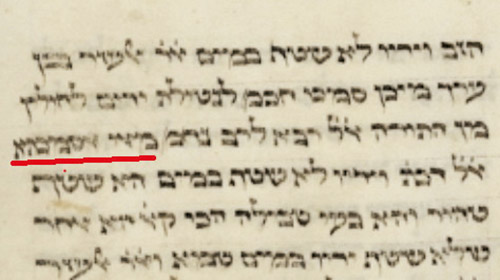

Related to the above is a girsalogical difference. We have Rava ask מַאי מַשְׁמָע—“what in the verse implies this?” But Hamburg 169, Vatican 122 and Vatican 124 have מַאי אַסְמַכְתָּא, thus making it evident that this is mere hint. Rashi and Tosafot don’t have this girsa. Indeed, it likely derives from סמכו and Tosafot’s stated position.

The third occurrence of this principle is Horayot 2b. The Mishnah had declared that if the court had issued an erroneous ruling, and one of the judges, or a student who was fit to issue rulings, knew that it was erroneous, and nevertheless acted based on the ruling, the judge or student is independently liable, and wouldn’t be covered in the sacrificial offering brought by the court. Abaye and Rava differ in explaining the Mishnah. Rava says “a student fit for ruling” are such as Shimon ben Azzai or Shimon ben Zoma, outstanding Torah scholars who weren’t ordained. Abaye objects: if so, they would be intentional sinners! (Or, rather importantly, in Munich 95: would this be errant?!) Rava replies דְּטָעוּ בְּמִצְוָה לִשְׁמֹעַ דִּבְרֵי חֲכָמִים, that they erred in thinking it a commandment to listen to the words of the Sages. Rava here means to heed their words despite knowing it is in error. (People often cite Rashi on Chumash literally, about following them even if they say right is left, but the topic is more complex, and one shouldn’t actually follow if they are wrong.)

Throughout, Rava reacts to בְּמִצְוָה לִשְׁמֹעַ דִּבְרֵי חֲכָמִים: to object to its extension/application to “kadosh”; to riff off its typical formulation; or to explain where it shouldn’t be followed. He still accepts its basic premise. Yet, Abaye more readily applies it.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.