Reviewing: “Hitler’s Volksgemeinschaft and the Dynamics of Racial Exclusion: Violence Against Jews in Provincial Germany, 1919–1939,” by Michael Wildt. New York: Berghahn Books, 2012. Published in association with Yad Vashem.

322 pgs. ISBN 978-0-85745-322-8.

In this work, Michael Wildt, a historian of modern German history in Berlin, examines Hitler’s Volksgemeinschaft (“people’s community”), the “appeal of modernity” and its ability to unleash a “transformative dynamic that contributed decisively” in providing legitimacy to the Nazi regime, specifically to the younger generation.

Wildt asserts the “production of Volksgemeinschaft was a process of inclusion that was supported by promises of equality, economic prosperity, and symbolic recognition.” It also required a dictatorship, concentration camps and secret state police. Employing terror was a key element of Volksgemeinschaft that should not be limited. In other words, the National Socialists succeeded in linking their platform with the “political hopes and desires” of the nation.

Antisemitism played a key role in establishing the Volksgemeinschaft by creating a Judenfrei (“Jew- free”) German Reich and a system to totally destroy the civil and constitutional order of Germany. German Jews would be eliminated from the Volksgemeinschaft through myriad government laws and ordinances, and by banishing them from daily life, while leaving the rest of the population unaffected. The rights of German Jews would be reduced, while Germany would be transformed into “an aggressive and racist Volksgemeinschaft.”

As historian Avraham Barkai noted, this does not suggest the Nazis had a master plan leading to the Final Solution. Yet, without the “prior deprivation, ostracism, and institutionalized plunder of the German Jews—in full view and with the increasing approval and complicity of millions of Germans—the Final Solution would not have been possible.”

Wildt takes issue with the late Raul Hilberg, whose seminal work “The Destruction of the European Jews,” maintained that the Nazi regime initiated a series of calculated and successive stages of state measures, laws, decrees and ordinances, which implied a “top down” approach, where the persecution of the Jews is defined by actions of the state.

Since the 1980s, a number of studies have exposed the fallacy of this analysis. Instead, the focus of Wildt and others is on the societal persecution of the Jews by neighbors, colleagues, customers, acquaintances and even relatives. Thus, the popular notion that the Germans under Hitler were forced by terror and violence to avow their fidelity to the Nazi regime is open to serious doubt. As one Social Democrat noted after Hitler’s triumphant visit to Munich on March 17, 1935, “One can force a Volk to sing, but one cannot force it to sing with such enthusiasm.”

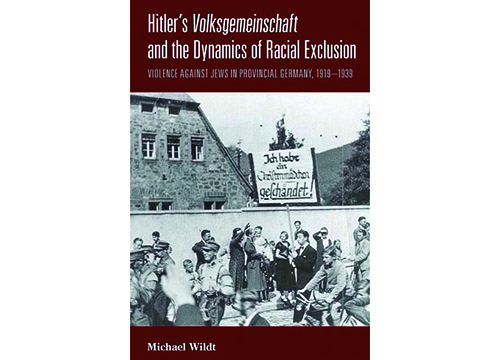

Though there has been a great deal of interest in how “ordinary men” could become perpetrators, Wildt wanted to understand the role of spectators, onlookers, the curious and those passing by, who become an audience when a Jew was being publicly humiliated, irrespective of their personal feelings toward the event. He cited one example in which there is a photograph of a young man in a dark suit being driven through the streets of Marburg, Germany on Saturday afternoon of March 19, 1933 by the SA (Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary organization of the Nazi Party) carrying a big sign that read, “I defiled a Christian girl!”

Parading in front of the SA is a brass band with sneering teenagers on bicycles. Curious bystanders line the sidewalks. One mother is holding her child, and another gives the SA troopers a “German salute.” People are laughing and not one person appears to contest or turns aside in revulsion at this antisemitic display.

Wildt recognizes one cannot know what the spectators in the photograph perceived about the young man being publicly shamed and disgraced, even if some individuals were revolted or felt pity. Though the spectators were not perpetrators, they were accomplices nevertheless—for without them serving as an audience, with streets devoid of people and shuttered windows, the SA spectacle would have fallen flat. “All spectators who accompanied the procession, Wildt said, even those with hesitations, “participated in the performance,” and became “active accomplices in anti-Semitic politics.”

Dr. Alex Grobman is senior resident scholar at the John C. Danforth Society and a member of the Council of Scholars for Peace in the Middle East (SPME).