By Alfred I. Neugut

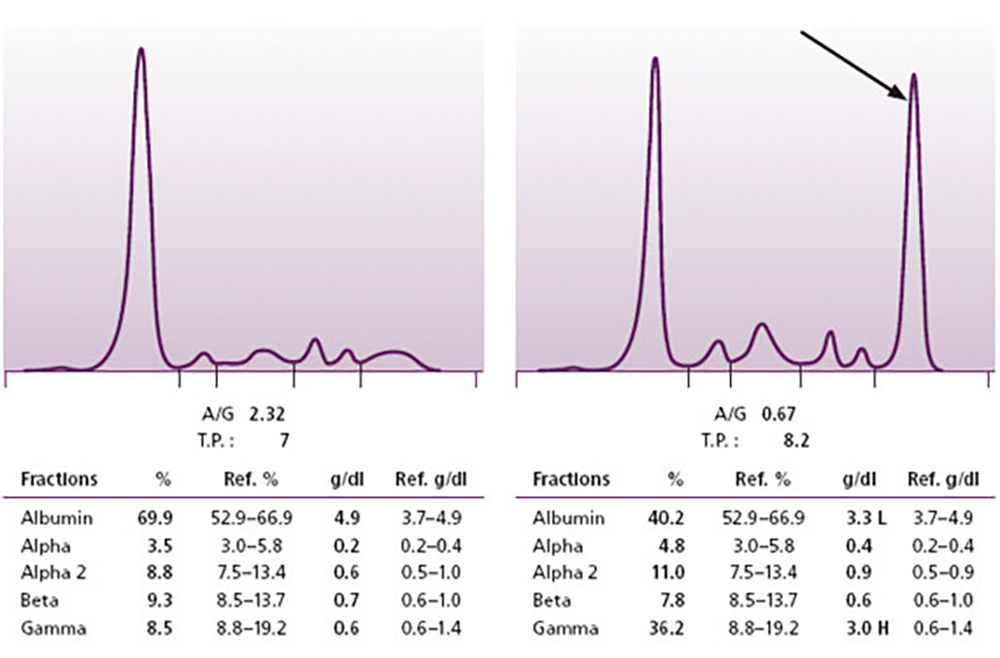

In the blood and serum of every healthy individual are normal levels of antibodies or immunoglobulins. They are the result of a lifetime of exposure to the foreign substances and toxins, microbes and vaccinations to which we are all exposed. We can clinically assay for the presence of these immunoglobulins with the use of a test known as the serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) on which our collected antibodies appear as a broad, homogeneous band.

If we do an SPEP on a random sample of White middle- or older-aged individuals in the U.S., we will find that a peak or spike will appear in approximately 1% of those tested, representing a single antibody or immunoglobulin clone from a single plasma cell that has proliferated and is producing an inordinate level of this M (monoclonal)-protein. Does that mean that 1% of the population has multiple myeloma? The answer is “no.” We discussed last week that multiple myeloma is characterized by a triad of characteristics in order to make a diagnosis. In addition to the presence of an M-spike on the SPEP test, there should be an excess of plasma cells in the bone marrow and also lytic bone lesions on an evaluation of the skeleton. If all three of these factors are present, then yes—the person does indeed have multiple myeloma. This is the typical presentation (there can be allowances for a bit more or less for each of these problems and still allow for a diagnosis, so please consult your physician for individual patients).

Returning now to our general average population of whom 1% have an M-spike: Do they have myeloma? The answer is that, while a very small fraction may have the other two symptoms I listed above, the vast majority will not, and will simply have an elevated M-spike in isolation. In part because they do not have the other manifestations of myeloma, these people with an isolated M-spike will generally have no symptoms or problems as in the CRAB spectrum (calcium, renal, anemia, bone) we described last week and would have been blissfully unaware of any issues if the SPEP were not performed.

This condition has received the name of MGUS (Monoclonal Gammopathy of Unknown Significance) though I am about to inform you of its significance (the name is somewhat outdated). As with the solid tumors, we are frequently aware of precursor lesions—adenomatous polyps are lesions which are in the pathway from normal colon cells to colon cancer; ductal carcinoma-in-situ is in the pathway from normal breast cells to invasive breast cancer—it appears that MGUS is a precursor lesion for full-blown multiple myeloma. Approximately 1% of MGUS patients will progress to full-fledged multiple myeloma annually, so that by 20 years, 20% of a cohort of MGUS patients will have developed myeloma (do the math).

We noted in our last article that myeloma was about two to three times more common in those of African descent than in Whites. The same can be said for MGUS. Thus, the progression from MGUS to myeloma is similar for both Whites and Blacks and, therefore, whatever the factors that are responsible for the racial disparities in this disease, they are operating prior to the onset of MGUS.

So for those of us who are super health conscious and hypochondriacs, should we rush out to our primary care doctor and ask her to add an SPEP to our blood panel the next time we undergo our annual wellness exam? A good question, but the answer is that, even if we were to discover that you indeed were one of the unlucky 1%, there would be nothing we could recommend to either treat the abnormal blood test or to affect its inexorable progression to full-blown myeloma. As a result, we do not do routine screening for MGUS.

I should also point out that there is an intermediate condition known as smoldering myeloma. This is something in between MGUS and full-blown multiple myeloma in which the individual has an M-spike and some of the further characteristics of myeloma but not the full spectrum of characteristics that would merit a diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Presumably this is an intermediary step in the progression from MGUS to myeloma. As with MGUS, there are no clear-cut measures known that can reliably interrupt the progression from smoldering myeloma to full myeloma, though frequent efforts are made to treat it with the same treatments that are utilized for multiple myeloma.

Alfred I. Neugut, MD, PhD, is a medical oncologist and cancer epidemiologist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York Presbyterian and Mailman School of Public Health in New York. Email: ain1@columbia.edu.

This article is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, and does not constitute medical or other professional advice. Always seek the advice of your qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment.