Rabbi Yehoshua ben Chanania (a second and third-generation tanna) was never defeated in verbal combat, except by a woman, a young girl and a young boy. He relates each of these encounters in Eruvin 53b. In the last of these, he meets a young boy at a crossroads and asks him which way to the city. The boy told him, “this path is short but long, while that path is long but short.” He took the short-long path, but when approaching the city, he discovered that orchards and gardens surrounded the city, which he would have to climb over. He retraced his steps, found the same boy, and asked him, “Didn’t you tell me the way was short?” To which the boy replied, “Didn’t I also tell you it was long?” He kissed the boy on his head, and praised him for his wisdom.

This story comes to mind whenever I come across a daf which either has lots of Gemara, in the center column, with little of Rashi or Tosafot’s commentary, or a daf which has very little Gemara and an abundance of Rashi and / or Tosafot’s commentary. The shape of the page often corresponds to the genre. For instance, a straightforward legal section doesn’t require much Rashi to explain the local plain meaning, nor Tosafot to object to Rashi’s explanation or contrast with foreign sugyot. Narrative (aggada) may require some of Rashi’s commentary, to explain the meaning of arcane terms, but not much in the way of Tosafot — consider Ketubot 103b. Terse legal reasoning, cryptic discourse or an argument that is difficult to follow or contradicts assumptions made more globally would require both Rashi and Tosafot’s commentary —consider Ketubot 108a. Since these commentaries wind around the central column, and that central column will widen to the left or right as each commentary terminates, the very shape of the text-blocks on the page will indicate what we’ll encounter. Lots of Gemara with little commentary is the long-short path, while little Gemara with lots of commentary is the short-long path.

The first page of Nedarim immediately struck me as a potentially short-long path. All that appears in the central column is a rather short mishna, and swarms of commentary. To see this yourself, open a Gemara yourself. Or, if you are using “Sefaria” as your digital resource, you can click on the passage. In the sidebar, instead of selecting “commentary,” select “manuscripts.” They currently have three: the Munich 95 manuscript (which is the only complete manuscript of Talmud Bavli, from 1342), the Bomberg Venice printing (from 1523) and the Romm Vilna printing (from 1880-86).

However, the complexity isn’t really there, for this page of Nedarim. The two primary commentaries wrapped around the Talmudic text are a more concise one dubbed “Rashi,” — but which wasn’t really composed by Rashi, but by the scholars of Mainz or others — and Ran (Rabbi Nissim ben Reuven of Girona), which is more verbose and contains both Rashi-like running commentary and Tosafot-like analysis. These primary commentaries frame the page and determine how much Gemara will appear. Wrapped around these but in much smaller font, in the Vilna Talmud, are commentaries by the Rosh (Rabbeinu Asher) and Tosafot.

Why are Rashi and the Ran given primary positions and the Rosh and Tosafot secondary in the Vilna Shas? It is based on the Venice printing. (Again, see Sefaria / manuscripts / Bomberg Venice.) While earlier printings (e.g., Soncino, Berachot printed in 1484) had the feature of commentaries wrapped around a central Talmudic text column, the Venice printing standardized the Talmudic pagination for us. That is, if you compare the first and last word on each page of the Gemara, that is identical for what we have (and for Nedarim, Rashi, Ran and Rosh). The Vilna Shas adopted this and also standardized the layout for us. That is, the shape of the text-boxes, and the first and last word on each line of Gemara, Rashi and Tosafot. Subsequent Talmudic printings typically conform to this layout, and only add material around the edges.

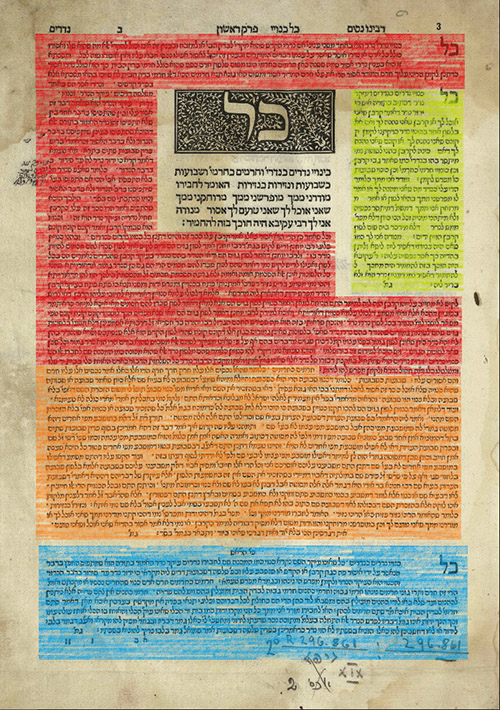

The Bomberg Venice printing of Nedarim has no Tosafot, but has Rashi (see image, where I’ve shaded it green) and Ran (shaded red, orange) wrapping the Talmudic text, and places the Rosh’s commentary in the same size underneath (shaded blue). The Romm Vilna printing conforms to that and makes Rashi and Ran primary, keeps the secondary Rosh and introduces Tosafot as another smaller secondary commentary.

As to the complexity of the sugya, what happens on Nedarim 2a is that we are dropped into the middle of an involved topic. The mishna discusses kinuyim, nicknames of vows, oaths, etc., and gives examples of yadot, shorthands. This is typical of mishnaic style which, for instance, begins brachot for start and end times of the night Shema without defining what “Shema” is, from whence the obligation and so on. The Ran begins his commentary on the masechet with a wonderful and clear introduction to the general ideas, so that we can tackle the mishnah in the Gemara with a semblance of a framework. He also has a Rashi-like running commentary on the Talmudic text — explaining phrase-by-phrase in the local sugya — and a few more global Tosafot-like concerns. This wordy, introductory essay is what grabs most of the page space, and limits the central text to just the mishna.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.