While the winter months provide a respite from the heat gathered walking the stuffy underground tunnels of the New York City subway system, the summer settles over everything with a glistening level of sweat and a subtle red tinge to the cheeks.

On one particular summer afternoon in June, on day 254 of the war, I ventured from my Brooklyn apartment and its air conditioning to Manhattan to 35 Wall St., a street that was, at the time, crawling with cops who stood around with thumbs hooked through the front of their uniforms, chatting with each other through the occasional bleep of a walkie-talkie.

With headphones in, my journey was folded between the sounds of guitar and drums, but when I stepped onto the cobblestone streets in that part of the city, I took the headphones out of my ears and put them in my pocket, wanting to stay on guard. I scanned the street for flags of green and red, and spotted a boy, walking some ways away from me, who was waving a large Israeli flag in the air. He wore a backpack and appeared to have nothing to do except walk around and wave his heritage in the air. I began to smile, joining a crowd of 20 people walking further inside the building. I looked around at the motley group of people, none of whom, at first glance, were outwardly displaying their religion. I wondered what brought them there, especially when the voices of hate had risen in the streets beyond.

In a small inner room, a large screen projected a five-minute video. The group watched Israeli interviewees, festival organizers and survivors describing the smiles and the dancing at the Nova Festival that ended on Oct. 7 at 6:29 am. I stood with my back pressed to the chalky walls that left marks all over my clothing like desert sand. The music pulled you into the trance that the dancers in the video were clearly experiencing, bringing a smile to my face just to watch joy and beauty flit across their face. I knew the darkness that would slam into them so soon, but for a moment us viewers could join their freedom and innocence.

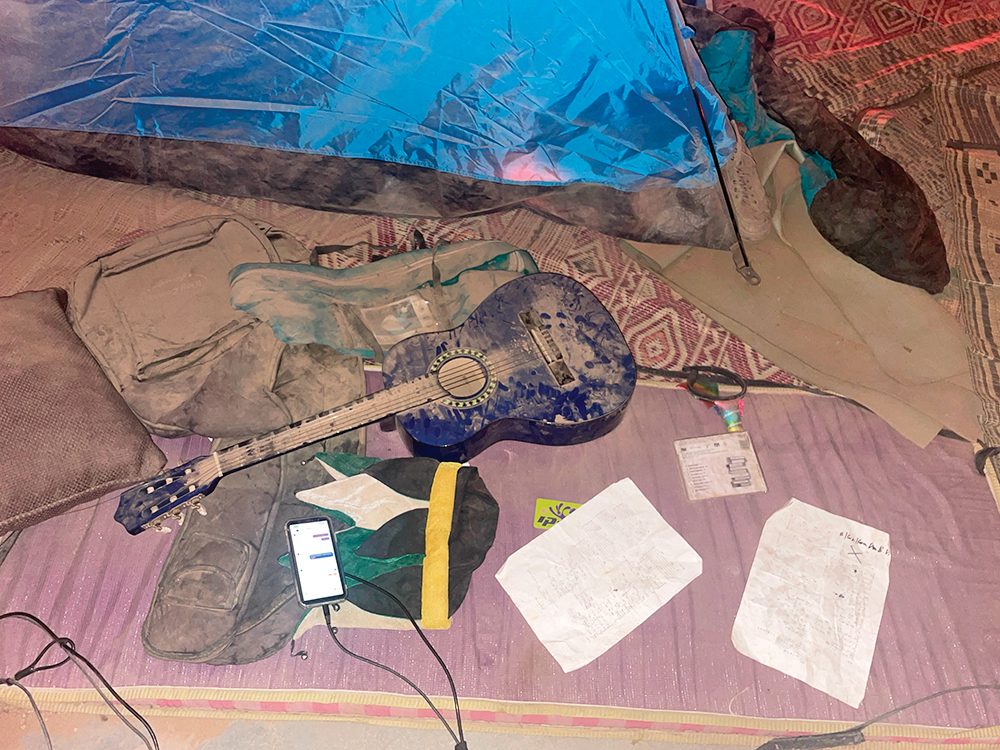

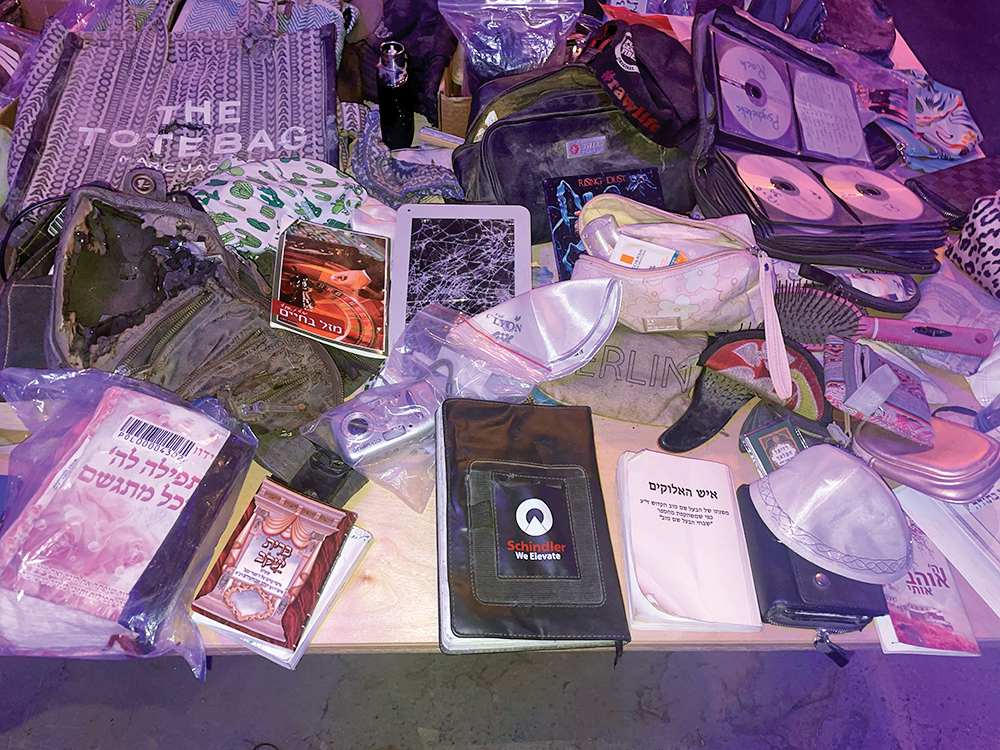

After the video ended, I found myself at the front of the line, inexplicably leading the group into the exhibit hall, where we were met with artifacts laid out, flown straight from Israel. Sandals, sleeping bags, bottles of sunscreen and crumpled plastic water bottles, all covered with a thin film of dirt and dust. Videos played on large screens and smaller phones and the screams and yells intermingled in the room. As I was there alone, I spent my time wandering through the maze of tents and belongings, taking my time with as many individual stories as I could, having a hard time stomaching watching videos taken by Hamas terrorists. Though many of the videos had parts that were blurred out, the voices of young men and women pleading for their lives or saying goodbye to their parents neither requires words nor is satisfyingly defined by them.

Continuing through the exhibit, I was faced with the skeletons of cars and portable bathrooms with tiny bullet holes peppering their surfaces. The feeling of death emanating from these was enough to make me feel physically nauseous and I had to pass by some signs without reading them. However, I was also met with art, music, light and a sense of hope that only the Jewish heart can rekindle again and again. The large room also had tables full of abandoned or now owner-less bags and shoes and a recreation of some of the festival’s decorations. Beyond that space, an alcove had faces and faces pasted to the wall. I left a note with the pictures of the murdered and said my goodbyes.

CDs, kippot.

In the outer room, there was a single burning incense wick on one of the tables that were set up on mats with tables and cushions laid out for visitors to talk and process. I laid straight down on the floor beside the incense for half an hour, hearing murmuring voices and low music playing. While the past eight months (at that point) had been a task in feeling and unfeeling the loss, horror, anger and grief which has plagued us globally as a nation, that day had been validation and a memorial.

Fast forward five months, and on day 418, on a trip to Israel for a family bar mitzvah, I finally traveled down south to Re’im, where the Nova festival was held, where the massacre occurred, and where the Simchat Torah war found its bloody beginning.

The drive from Jerusalem turned slowly from plain highways to those same roads steadily filling with yellow ribbons and signs calling for the return of the hostages as I got closer to the homes and communities whose backyard was home to atrocity and chaos on that day. Before arriving at the memorial site, my companions and I stopped in different bomb shelters on the side of the highway, some over a mile away from the site of the festival. Their insides were covered with a fresh coat of paint to hide the blood spatter, stickers and writing screaming out pain, loss and fierce survival in every one, and a littering of memorial candles, burnt out or still lit. Some had signs with the stories of those who had lost their lives in the same space we now stood in, over a year later.

Further down the road, in the area itself, the site was bustling with people. A class was there, having a gathering to remember their teacher who was killed. An entire unit of IDF soldiers in uniform wound their way through the memorial. A map showed different notable places around the grounds where some stories occurred that were references in different signs. Volunteers and artists had created the idea for the memorial, which included a sign with the joyful face of each person murdered at the festival, as well as the personalized space each victim had in that field of faces.

Set up in a way that allowed you to move through slowly were posts in the ground adorned with a picture, words, a story, candles, flowers, stones, and whatever other specified objects or quotes were used regularly by each individual. Some posts were linked together by string or surrounded by the same circle of white stones to symbolize they had been in a relationship or come together to the festival. Weaving through the entire exhibit was the same red anemone flower that blooms in the Re’im forest during winter and has become a symbol of the Nova festival and memorial.

Another part of the site had an entire spanning field of newly planted trees, one in memory of each massacred person, and yet another area had big signs telling certain individual stories that had been pieced together through phone calls and location data, telling the harrowing tales of injury, escape and eventual death. Many different people were often linked together by one location that led to their deaths, with signs conveying how each one had ended up in that place. Reading detailed descriptions like these hit especially hard, and I found myself lingering there the longest before we left the site.

Going to both the mobile exhibit and the site of the Nova festival is not comparable, but gave me an opportunity to feel, as much as I could, a part of the pain of that day, in stages and in starkly different ways. The exhibit aims to tell the story of “the moment music stood still,” to show the stark difference between the peaceful festival goers and the horrid actions of Hamas attackers, “to empower visitors to responsibly explore and bear witness” — and it does this wonderfully. The exhibition is crucial for those who cannot make the trip to Israel, whose connection to the land and the people is faraway and perhaps clouded by the media of the world. The exhibit smooths out the distortions the world has made about the massacre, making it clear that there is nothing political about innocent loss of life, in those who were celebrating the same music that you and I listen to.

The memorial in the south of Israel appeals to the beautiful inner ability of the Jewish nation to feel our pain in the spaces and time we allocate to doing so. The dedicated time it clearly took to set up and research each aspect of the site and the beautiful art that covers every inch of this place that was turned to darkness on that day serves to remind us that we will always try to pull and pry the dial back to light. More especially, it tells us that shining a light on the dark places that exist in life does not, as we fear, allow them to take over everything, but rather creates a blended gray space that integrates the bloody past into the difficult present.

In both experiences, to me, it became clear that the hardest part is that you must turn away, you must continuously turn away. No matter how many stories I read and cried over, there was one more I would not be able to get to, or some detail that is forever lost to the events of that day. Yet the flag, bloodied and trampled, continued to wave in that space, which was the emphasis planted in the flowers and trees, the emphasis carried through the traveling exhibit, which has since made its way to Los Angeles and Miami.