Rabba (bar Nachmani) and Rav Yosef (bar Chiyya) were third-generation Amoraim situated in Pumbedita, and were frequent disputants. Rav Yehuda (bar Yechezkel) was their teacher and the prior head of Pumpedita academy. When Rav Yehuda died (Brachot 64a), it was unclear who would next lead the academy. Rav Yosef was “Sinai”—that is, expert in tradition, so was a font of knowledge akin to Mount Sinai. Rabba was an “uprooter of mountains,” expert in incisive reasoning. (Note also that Har Sinai is a mountain.) They asked for advice from the sages of Eretz Yisrael, who responded that Sinai takes precedence, for everyone needs the owner of the wheat, that is, the sources from which to reason. Even so, Rav Yosef refused the appointment since Chaldean astrologers had told him that he would preside over Pumpedita academy for two years. In this way, he cleverly extended his life. Rabba presided over the academy for 22 years, and Rav Yosef, subsequently, presided over the academy for two-and-a-half years.

Since they so frequently argue, it would be nice if there were a way of deciding who wins. Now, often when Amoraim argue, they argue their case with evidence and logic. Alternatively, later Amoraim pick up the thread and endorse a position. Then—within the sugya—it’s obvious who wins. There are still plenty of instances where the conclusion is left uncertain. What should we do then?

Well, we could ask Rav Yosef! A baraita (Avoda Zara 7a) discusses what happens when two sages sit together and disagree whether something’s pure/impure, permitted/forbidden1—follow the sage who’s greater in wisdom or number. If they’re equal, rule stringently. Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korcha disagrees: in biblical law, follow the stringent position; in rabbinic law, follow the lenient position. Addressing this baraita, Rav Yosef endorses Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korcha2. Indeed, for many unresolved questions, Rishonim adopt this Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korcha approach.

On the other hand, maybe their respective strengths—Sinai versus Mountain Uprooter—can inform us to whom to lend greater credence. Is it a matter of mustering sources, interpreting them or reasoning? Also, perhaps, Rabba had greater influence over those 22 years, so an unspoken consensus emerged like Rabba. Maybe Rav Yosef—who outlived Rabba—had the last word. We know of other decisive principles, such as ruling like the temporally later Amora, or like the teacher over the student. There are general statements such as that Rav wins over Shmuel in matters of prohibitions, and Shmuel wins in monetary matters. We don’t like existing in a state of doubt. If only there were such a decisive rule for Rabba and Rav Yosef …

Rabba Wins in Gittin

Indeed, there are two such decisive statements, one in Gittin (74b) and one in various forms in Bava Batra (12b, 114b, 143a), indicating generally ruling like Rabba. Tosafot wonders why particular statements favoring Rabba are necessary, on Kiddushin 9a. The Kiddushin sugya was my original focus, but since it’s a lengthy topic and we just finished Gittin, let’s deal with Gittin first, and address other sugyot next week.

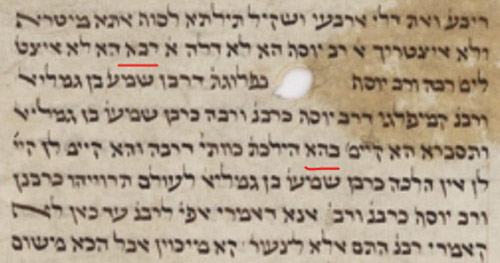

In Gittin 74b, where a landowner promised a sharecropper a greater share for an extra watering, but rain made the extra watering unnecessary and unperformed, Rav Yosef says he need not pay an extra share; Rabba disagrees, since the land was watered. The Talmudic narrator tries to align Rav Yosef with the (disagreeing) sages and Rabba with Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel of the preceding mishna, who testified that in a case in Tzaydan, of a get contingent on return of a cloak which turned out to be lost, they validated the get but required her to pay its value. The Talmudic narrator rejects this, saying וְתִיסְבְּרָא?! וְהָא קַיְימָא לַן הִילְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַבָּה; וּבְהָא—אֵין הֲלָכָה כְּרַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל! Does this make sense? “We establish that the halacha is like Rabba; and in this, the halacha is not like Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel3. Therefore, they cannot align!”

Tosafot (ad loc.) notes a difference between how the Gemara stated the halacha is like Rabba, with no modifier, and like Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, with the modifier וּבְהָא, “and in this.” They deduce a general rule like Rabba across the entirety of Talmud, but wonder how it interacts with other statements.

Because I’m a troublemaker, I’ll register two objections: First, Rabba regularly is regularly listed before Rav Yosef— רַבָּה וְרַב יוֹסֵף דְאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהו appears 38 times in Talmud, never reversed. So too in disputes, such as Zevachim 120a, Bava Kamma 56a and Moed Katan 2b, Rabba appears first. There are a few exceptions, such as Shabbat 148b, but that’s what’s under discussion. In Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim, Rav Aharon Hyman explains that this is because Rabba led Pumpedita first. Indeed, Rosh Bava Metzia 4:17, the Rosh notes that the redactor, Rav Asha, always places Abaye before Rava because Abaye headed Pumpedita academy first; since the sugya in Bava Metzia had “Rava” first, it must be a scribal error for Rabba.

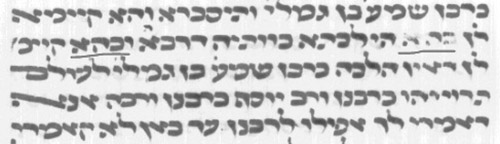

Then, the Talmud lists Amoraim chronologically. The practical ramification there is to rule like the temporally later Amora, Abaye. Similarly, here in Gittin 74b, Rav Yosef’s position is uncharacteristically listed first, so, perhaps, we should have his disputant as Rava. This would also explain how we know to rule like Rava/Rabba, despite no overwhelming supportive sources or logic. Indeed, Vatican 140 initially recorded it as Rava, in the original dispute, then rubbed out the upper leg of the aleph to transform it into a heh.

Second, does it really have וּבְהָא by Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel and not by Rabba? Vatican 140 moves בהא earlier, so that it refers to either Rabba exclusively, or to both clauses! Similarly, Oxford 368 has בהא in the Rabba clause, paralleling the later clause, but it’s subsequently rubbed out.

My kvetching might answer Tosafot’s difficulty in Kiddushin 9a, why bother ruling like Rabba in a particular case given the general rule. The answer may be that we don’t actually generally rule like Rabba! (The drawback to this might be rewriting swaths of Shulchan Aruch.) Next week, we’ll consider the general rule stated in Bava Batra, as well as the “vehilcheta” like Rabba on Kiddushin 9a.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 For monetary disputes, the law might be hamotzi meichaveiro alav hara’aya, with the current possessor able to keep the item / money.

2 Rabba doesn’t take a contrary position to this.

3 See Gittin 83a, that Rabba bar bar Chana cited Rabbi Yochanan that halacha is always like Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel when he appears in the mishna, except for three cases, Tzaydan being one of them.