No law can guarantee financial outcomes

The principal method for governments to effect change is to enact and enforce new laws—with taxes, regulations, incentives, and punishments. But a quick glance at current events indicates legislation hasn’t ended global religious and political tensions, lowered unemployment, restored deflated real estate values, or prevented natural disasters. This has been the case throughout history—under monarchies, Marxists, or representative democracies—because there are natural, social, and economic factors that can’t be controlled by legislation.

This doesn’t stop governments from trying to control these uncontrollable factors. And the decisions of policymakers definitely impact the financial well-being of individual households. So how does one plan for the impact of national economic policies that may not achieve the intended results?

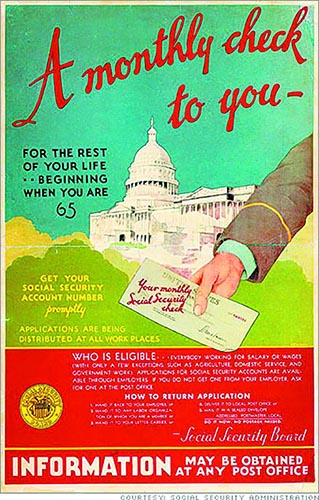

Sometimes a look to the past can provide some insight for the future. A case in point is Social Security, an ambitious government economic program that began 75 years ago.

The great ideal behind Social Security

In June 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt presented to Congress a new social insurance program intended to provide economic security for the aged. His plan called for workers to contribute to their own future retirement benefit by making regular payments into a joint fund administered by the federal government.

Roosevelt explained his rationale: “Security was attained in the earlier days through the interdependence of members of families and of the families within a small community upon each other. The complexities of great communities and of organized industry make less real these simple means of security. Therefore, we are compelled to employ the active interest of the Nation as a whole through government in order to encourage a greater security for each individual who composes it….”

The original plan

After more than a year of discussion and alteration, the Social Security Act was signed into law in August 1935. In 1937, workers and employers began paying Social Security taxes, and in 1940, eligible retirees (those over age 65) began receiving benefit checks. In order to qualify for benefits, workers needed to work a minimum number of years, and the size of the monthly benefit depended on one’s earnings history.

The original plan exempted the self-employed and workers in several other fields. The initial tax rate was 2% (the employer and employee paying 1% each), applied to a maximum of $3,000 in wages. The original Act called for gradual increases in the tax over the next 12 years. An informational pamphlet explained: “And finally, beginning in 1949, 12 years from now, you and your employer will each pay three cents on each dollar you earn, up to $3,000 a year. That is the most you will ever pay.” (emphasis added)

Observation #1: With Government Plans, Cost Overruns are Inevitable

By and large, politicians are not good at long-term projections. They just aren’t. (Honestly, when was the last time any government project came in under budget?) So it is no surprise that the costs for providing Social Security have far exceeded the original promises. Some of the cost overruns can be attributed to those social and economic forces that legislation can’t control, like increased life expectancies and the distorted demographics of the Baby Boom. The end result? More people, living longer, and receiving larger sums of benefits.

And oddly enough, it took a while for legislators to address the problem. Congress delayed increasing Social Security taxes so that the 6% total tax scheduled for 1949 wasn’t collected until 1960. Then, to catch up with the demographics, the tax rate doubled over the next three decades. But in 2010 and 2011, Congress temporarily dropped the Social Security payroll tax during 2011 and 2012 from 12.4% to 10.4% by decreasing the amount paid by the employee.

Over time, the portion of income subject to Social Security tax increased as well. Indexed for inflation, $3,000 in 1949 was the equivalent of $27,583 in 2010. The amount of income subject to Social Security in 2010 was $106,800. Adjusting for inflation, the higher tax rates and higher income threshold result in a tax that is eight times greater than the “most you will ever pay” promised in the original plan.

Elozor Preil is Managing Director at Wealth Advisory Group and Registered Representative and Financial Advisor of Park Avenue Securities LLC (PAS). He can be reached at [email protected]

See www.wagroupllc.com/epreil for full disclosures and disclaimers.

Guardian, its subsidiaries, agents or employees do not give tax or legal advice. You should consult your tax or legal advisor regarding your individual situation.

By Elozor M. Preil