On Yevamot 27a, we encounter Rabbi Abba bar Mamal, who interprets a brayta as reflecting Beit Shammai’s position. This would constitute a rejection of the prior interpretation, which reinforced Rav Ashi. Both the Artscroll and Koren English translations make this rejection explicit. Artscroll translates “This inference is rejected: R’ Abba bar Mammal said: No! Whose opinion is reflected in this brayta?” Koren translates: Rabbi Abba bar Memel rejected this explanation and said: In accordance with whose opinion is this baraita taught?” (Both are interpolated translations, where helper gloss text appears unbolded alongside bolded literal translation text. The gloss aids in framing and explicating the otherwise quite terse Talmudic text. Grammatical English sentences often require greater elaboration, identifying who said what or the resolution of ambiguous antecedents, so I find them useful to consult.)

The reader might imagine that Rabbi Abba bar Mamal heard Rav Ashi’s interpretation of Shmuel, or the Talmud’s bolstering of that interpretation, and forcefully rejected that. However, that is not quite possible, considering rabbinic biography. Rabbi Abba b. Mamal was an Amora of Israel who lived until the third Amoraic generation, interacting with Rabbi Ammi and Rabbi Assi, but who also reached back to the first Amoraic generation. His teacher was Rav Hoshaya Rabba (first generation), and perhaps even saw Rav (first generation) when the latter was in Israel. It is therefore unlikely for him to respond to a sixth-generation Rav Ashi, or to an even later perhaps-Stammaic support to Rav Ashi from a brayta. They are too separated by time and space.

Possible resolutions include: (a) Emend Rav Asi to Rav Assi, the first-generation Babylonian Amora. (b) Emend Rav Ashi to Rabbi Assi, a third-generation contemporary of Rabbi Abba bar Mamal. Sometimes such scribal errors occur, but I don’t see any manuscript support. (c) Understand that the Stamma frames it as such a dispute, but Rabbi Abba bar Mamal’s analysis stood alone and prior to Rav Ashi’s analysis or the Stamma’s supportive brayta interpretation. The last makes sense.

Patronymic?

Why is Rabbi Abba dubbed “bar Mamal”? Rav Aharon Hyman notes that this distinguishes him from his contemporary, a different Rabbi Abba, though sometimes plain Rabbi Abba does refer to bar Mamal. Consider Yevamot 105a. Rabbi Abba bar Mamal sat before Rabbi Ammi, where the yevama performing chalitza spat before removing the shoe, where Rabbi Abba bar Mamal insists she shouldn’t spit again. In the parallel Yerushalmi, he’s simply Rabbi Abba.

Hyman cites three explanations for “bar Mamal.” The vocalization of ממל as Mamal, Mammal, or Memel presumably follows the selected interpretation. (A) the obvious, standard explanation: Mamal was his father’s name. (B) perhaps he was from the town of Mamle. See Bereishit Rabba 59:1, where Rabbi Meir travels to מַמְלָא and because of their sickly nature, believes them to be descendants of Eli the kohen gadol. Also see Bava Batra 137b, where Rav Bibi b. Abaye is insulted as מוּלָאֵי, descended from truncated people, and Rashbam, who links it to Abaye descended from Eli (Rosh Hashanah 18a), and the aforementioned Midrash Rabba. See also Eruvin 51b, מַעֲשֶׂה בְּאַנְשֵׁי בֵּית מֶמֶל וּבְאַנְשֵׁי בֵּית גּוּרְיוֹן בְּאָרוֹמָא שֶׁהָיוּ מְחַלְּקִין גְּרוֹגְרוֹת וְצִימּוּקִין לַעֲנִיִּים בִּשְׁנֵי בַצּוֹרֶת. In translating Beit Memel, Rav Steinsaltz explains it as a family name. However, Jacob Hamburger, in Real-Encyclopädie Des Judentums: Talmud und Midrasch, connects it to a location, noting that the Arabs refer to Birkat el Mamila as the upper conduit in the Gehinnom Valley. From there, we have Mamilla Street and Mamilla Mall.

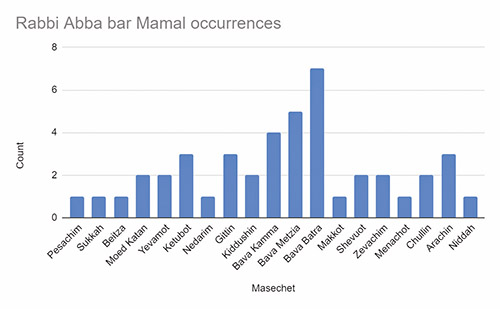

Finally, (C) we (and Maharatz Chajes) can point to Bava Batra 67b. When the Mishnah declares that one who sells an olive press implicitly includes the “Memel,” Rabbi Abba bar Memel explains that a memel is a מַפְרַכְתָּא, the utensil used to pound and crush the olives. Hyman rejects the idea that such a prominent Amora, quoted more than 40 times, is named for this one exposition. I find his rejection fairly persuasive. However, given a contemporary by the same name, perhaps if a tradition were particularly important, his colleagues could have assigned him that name to disambiguate, especially if he were exceptionally active in this area of halacha. (See chart for a distributional view of Rabbi Abba bar Mamal’s halachic output.)

Further arguing against (C) is that several other rabbinic scholars bear the “bar Mamal” descriptor. There is Rav Zeira bar Mamal (fourth generation, Bavel), Rabbi Yehoshua ben Mamal (fourth-generation Tanna), Rabbi Yossi ben Mamal, and most importantly, Rav Lily bar Mamal (third-generation Amora, Bavel). The names Abba, Lily and Mamal all involve sound duplication, so I’d guess it’s a patronymic.

Still, (C) prompts the more general question of eponymous Talmudic statements, and an unfortunately popular scholarly contention that these are pseudepigraphic, and evidence that many or all Talmudic attributions are similarly fabricated. (Indeed, Louis Jacobs points to Abba bar Mamal as an example of attribution due to pun.) Another somewhat Pesach-topical example is רַב קַטִּינָא, who explains that when the Mishnah (Bava Batra 93b) says a buyer accepts ¼ kav of impurities in grain, it means an admixture of legumes (קִטְנִית) rather than dirt. This broad topic merits a dedicated article, but consider that Rav Ketina might be drawn to repeat teachings about kitniyot, just as I’m drawn to think about derashot about Yehoshua bin Nun.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.