There are more than a dozen communities in Long Island today where Orthodox Jews can take advantage of a plethora of shuls, day schools, and kosher restaurants—and live a very comfortable life as Torah observant Jews.

But it wasn’t always that way.

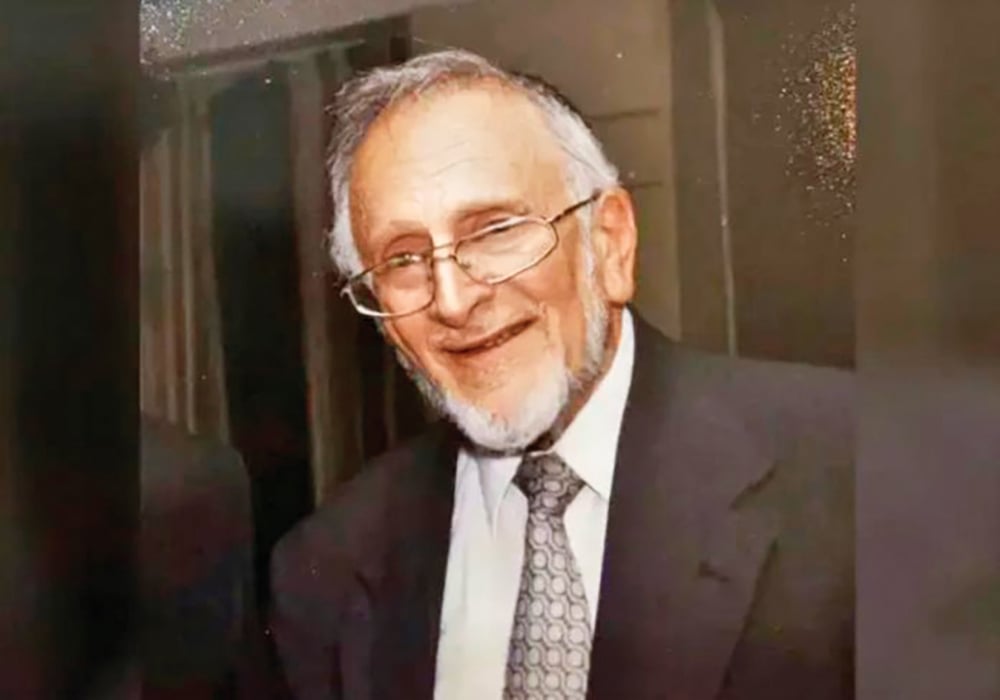

In the early 1950s, a young man named Rabbi Meyer Fendel, fresh out of school and working at his first job at Torah Umesorah, noticed that Long Island had a growing Jewish population but few, if any, Orthodox Jews. This was the height of the Conservative movement in Jewry; in fact, many folks at the time believed that Orthodox Judaism would gradually disappear.

Rabbi Fendel was determined not to allow Torah observance to die a slow death, so in 1953—with the support of a handful of local Orthodox rabbis and pioneering lay leaders—Rabbi Fendel and his beloved wife Goldie founded the Hebrew Academy of Nassau County (HANC), with an initial enrollment of only 32 students.

Today, more than 70 years later, HANC has about 1,200 students in its school and is recognized as one of the leading Modern Orthodox day schools in the country.

I have some very personal memories of Rabbi Fendel. Our family moved to West Hempstead in 1966, and one of the main reasons my parents chose the community is that they knew there was an established Modern Orthodox and Zionist-oriented day school in the area for their children.

My closest friend at the time was Hillel Fendel, Rabbi Meyer Fendel’s son, who was in my grade. I spent countless hours at the Fendel home with Hillel after school and on Sundays, playing dice baseball (a simulated baseball game, in which we created teams with made-up players) and reviewing all the popular tunes we enjoyed listening to on WABC-AM. Shabbat afternoons were often spent at Rabbi Fendel’s home, where we enjoyed a seudah shlishit meal and then walked to shul for Mincha and Maariv. Although it seems odd that I would spend my free time at the home of the school principal, Rabbi Fendel and his wife Goldie always made me feel comfortable in their warm and nurturing home. (Of course, Goldie Fendel’s chocolate chip cookies were also a major incentive!)

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Rabbi Fendel was also the first rabbi at the Young Israel of West Hempstead. He realized that if the new school was to succeed as an Orthodox day school, there also needed to be a shul in the area because that would encourage others to move to the community.

West Hempstead was a very special community back then; there was a real sense of family, which permeated in both the shul and the school … and much of that credit goes to Rabbi Fendel.

One of Rabbi Fendel’s greatest strengths was an eye for talented teachers, and I was fortunate to have had several teachers at HANC who influenced me strongly. Mr. Mechanic and Mr. Lilienthal, my fourth and fifth grade Chumash teachers, were each superb Tanach teachers. I owe them a debt of gratitude for my current practice of always reviewing the parsha each week to try to find new insights into the Torah reading. (Interestingly, neither of the two was a rabbi, but they each knew their Chumash well. I wonder if they would even be considered to teach in a day school today.) I also was fortunate to have an English teacher named Judith Lynch, a former nun who taught me the importance of writing well. I believe I might have been the only student in the class who truly enjoyed the challenge of diagramming sentences! (I included a thank you to her in the introduction to my book as I firmly believe I would not be able to write as well as I do if it were not for Mrs. Lynch.)

I have so many fond memories of my days at HANC. Rosh Chodesh breakfasts, elementary school plays; Mr. Mechanic’s mitzvah sheets; Al dishing out soup to students in the lunchroom; Mrs. Provda in the office; the Chidon HaTanach; Rabbi Kovitz teaching Gemara, Chumash, chemistry and math,; Mr. Lilienthal charging us a penny for each English word spoken during class and then making a party with the accumulated sum; Seymour Silbermintz leading a mixed-gender student choir; and it was all choreographed so brilliantly and seamlessly by Rabbi Fendel.

Rabbi Fendel was also an innovator par excellence. When he realized he needed more space for the school, he capitalized on the sale of a famous United States Air Force base at Mitchel Field in Uniondale, New York, which the federal government was dissolving and distributing to religious institutions. I clearly remember the bumper stickers that were distributed to parents: “HANC in Mitchel Field in ’66!” A couple of years later, HANC opened its middle school campus in a brand-new building at Mitchel Field, which is where I went to school.

Another one of Rabbi Fendel’s innovations was the “New Opportunities Program,” which he developed in 1971 and which is still in existence 53 years later. It allowed for students with little or no Judaic background to attend a Jewish day school while also receiving an excellent general studies education. This was well before the ba’al teshuva movement took off, and before day schools and yeshivot began accepting such students. Rabbi Fendel sincerely believed that every Jewish child should be entitled to a Torah education, and thousands of students (and their children and grandchildren) are now observant because of his heartfelt commitment to them. In addition, under Rabbi Fendel’s leadership, tuition was never a stumbling block to enable a child to attend HANC. It should also be no surprise that the first Yachad shabbaton was held at HANC.

He also embraced technology. In 1969, well before video technology became popular, he purchased a closed-circuit TV system for teaching ethics. One of the things I remember him filming was an ethical test of students: he placed a dollar bill and a crumpled piece of paper on the floor in the hallway, to see whether students would pick up both—or just the dollar bill. The videotapes were played in the classrooms via the closed-circuit system, and it served as a springboard for class discussion on what motivated the various reactions. Rabbi Fendel firmly believed that if you prepare students in advance to deal with ethical dilemmas, they will meet future challenges more successfully.

Of course, the school was known for its strong commitment to Israel and teaching Zionism, which apparently stemmed from Rabbi Fendel’s admiration of Rav Kook. The West Hempstead community was always one of the largest feeders of olim to Israel. More than a dozen families from West Hempstead immediately decided to make aliyah after the Six Day War. Even during the slow period of aliyah (1975-2000), the West Hempstead community always had a sizable number of families making aliyah, not in small part due to the Zionism that was taught and promoted to HANC students by Rabbi Fendel. I don’t know if there is an official count, but I’ve been told that there are more than 400 HANC graduates who have made aliyah.

Perhaps the best tribute to Rabbi Fendel was offered by a former student, Sari Holtz, who posted the following on Facebook:

Rabbi Fendel was more than a man of faith—he was a builder, a dreamer and living proof that with enough determination anything is possible. When he saw a community in Long Island with no Torah education, he didn’t just wish for change, he made it happen. Where others saw obstacles, he saw opportunity.

Rabbi Fendel founded HANC, starting with just 30 children in a worn-down house. Through relentless effort, he transformed it into a beacon of Jewish education, touching thousands of lives (including my own).

Rabbi Fendel’s legacy reminds us to ask ourselves: What am I building? How can I turn challenges into opportunities? How will I leave my mark in this world?

Let his story inspire us to chase our dreams and not to let fear stand in our way. May his memory be for a blessing.

Amen.

Michael Feldstein, who lives in Stamford, is the author of “Meet Me in the Middle” (meet-me-in-the-middle-book.com), a collection of essays on contemporary Jewish life. He can be reached at michaelgfeldstein@gmail.com.