Every year we read on Rosh Hashanah about the pain and struggle of infertile women; Sarah faced her challenges and was eventually rewarded with a son, and Chanah had a tremendous journey before having her son. We have all read these stories numerous times and I have written before that they are an opportunity for us to be sensitive to those people in our own communities who are undergoing their own struggles with fertility. These can be family members, co-workers or the people who sit next to us in shul. While they may not appear to be suffering and may not even speak about the challenges they face daily, they are still in pain and hurt silently. It is appropriate for us to be sensitive to their needs and be careful to say the right thing and to be even more careful to steer clear of sensitive and painful subjects and not say the wrong thing.

It is interesting that the reading for Rosh Hashanah focuses on fertility and having children, which are perhaps symbolic of the whole concept of renewal and the birth of the world. Birth of the world is expressed and symbolized by the birth of children and the renewal of families.

However, while this reading may be very apt for those thinking of others who are having fertility problems, for those actually going through fertility treatment their reaction may be very different. Fertility is not some distant idea for them; for them it is the entire fabric of their life:. They think about fertility treatment every moment of their waking hours and dream about it at night. One of the places of solitude is the synagogue. Here they can come to pray and be one of the congregation; here they can detach from the difficult reality of their medical situation and connect to Hashem. And then we read about Chanah and her fertility problems, and this is the major theme of the day, and the rabbi, wanting to raise the sensitivity of his congregation, speaks about infertility and the couple may feel trapped and unable to get away from their problematic situation even in safe haven of the shul.

This completely changes our perspective on the place of such a reading and its effect. Another problem with Chanah is the happy end; her prayers are answered and she has a child. But for a couple in the middle of a treatment, and even more so for one who has just experienced yet another failed cycle of treatments, the happy end seems completely unattainable. This is even more painful to listen to.

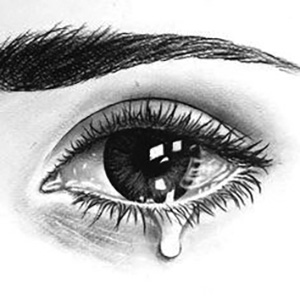

In discussing this portion of the Tanach with people facing their own fertility challenges, we can find a new meaning and subtle ideas in the story that may resonate with them. The first concept is that Chanah struggled with infertility and the Tanach stresses this. “She wept and would not eat” (Shmuel I 1:7). She was sad, depressed and suffered so much that her husband implored her to eat and be positive, enjoying the wonderful relationship that they had and placing less importance on having children. (See next verse.) Even after his request and her acquiescing and agreeing to eat and drink, she was still sad; she could function, she did cheer up, but her pain was still raw and overpowering. “She was depressed” (ibid. 10).

It is legitimate to cry and be overcome by the emotion of infertility. Chanah is presented as a model of the infertile woman whose story can resonate with other women. She cries, and when she is told she is exaggerating and harming herself she eats and drinks but does not and cannot now be happy. She is distraught.

The next words in the text guide us as to how she used her pain and anguish: “she was depressed and she prayed to Hashem, crying a lot.” She turned to the Almighty and still prayed; she did not leave the synagogue or refuse to attend services. She did cry before, during and after her prayers; she never cut off her reliance and belief in Hashem and His infinite and ultimate goodness.

In addition, she was able to cry publicly; she did not disappear into an inner room or reality but shared her pain and sorrow with anyone who was sensitive enough to notice. Many people find it so hard to express their emotions in front of others. As a result, many surrounding them are sadly unaware of their pain. Chanah was able and willing to share her emotional state; while not everyone can be as open and clear as this, it can be advantageous to be a little more open about what they are going through, at least with people close to them.

There is one more aspect of the story that can resonate with couples experiencing difficulties getting pregnant. After she pours out her heart in true prayer and longing, Eli, the kohen, approaches her and assumes she is drunk. Since the custom until then was to pray without moving one’s mouth, he quickly drew the conclusion that she was inebriated and that was why she was acting in this unusual manner.

Not only did he draw a false conclusion, but he rebuked her quite publicly: “How long will you be drunk? Remove your wine from yourself” (Shmuel I 1:14). She replied with the most honest and simple answer that she was depressed but not drunk, praying and pouring out her heart. She did not need to sober up; rather she needed to be allowed to pray.

The halacha is that we need to pray silently while moving our lips, and we deduce this from Chanah’s genuine prayer. Eli was wrong and Chanah was correct. Even great people can be mistaken and say the wrong thing; they can be convinced they are trying to help and read the situation as they see it, but they can be wrong.

Anyone undergoing a period of infertility will tell you that they have faced other people’s insensitive and sometimes just silly comments. “Calm down and everything will be OK,” “My friend had infertility and now she has five children,” “Just look at Sarah, she had children when she was 90 years old; you’ll be fine,” and any other variation on this theme. People are trying to be nice but they are mistaken, and if Eli was wrong, even though he who was the kohen and communicated with the Almighty, then regular people can be wrong and say the wrong thing. They are not being mean, they are just being human.

This is also a lesson for the rest of us: as we enter the new year we can try to be more empathetic and sensitive to other people’s needs. We can just be there and listen without passing judgment and giving out “good” advice. We can cry with others and pray with and for them even when we cannot console them, and we can allow them to pray in a safe environment where they can communicate with Hashem and allow Him to solve their problems.

This provides a deeper understanding of the story of Chanah that can be beneficial for those facing fertility challenges and those who are fortunate not to.

K’tiva VaChatima Tova!

By Rabbi Gideon Weitzman

Rabbi Gideon Weitzman is a senior rabbinic advisor for PUAH.