Introduction

In this article I will attempt to show the intimate connections between seemingly insignificant procedures in shul during davening on the one hand, and the service performed in the Beit Hamikdash (BHM) on the other. Because of length constraints on this article I chose to discuss just two actions that are customarily done in shul: 1) When two sifrei Torah are read, someone holds the second while the first one is read. When the reading is finished, the first Torah is moved to the right on the shulchan and the second one is placed down on its left, and Kaddish is recited over both. Then the first Torah is removed (hagbaha) and the second one is read. 2) When the chazan walks from his position (think of it as at six o’clock on a clock face) toward the aron (think of it as at 12 o’clock) to take the Torah, he moves to his right (6->5->4->…->1->12). He continues the counter-clockwise motion when he takes the Torah back to the shulchan (12->11->10->…->6). When returning the Torah from the shulchan to the aron, he again moves counter-clockwise and completes the circuit when he returns to the shulchan. In a similar vein, when we turn around toward the back of the shul as we say “Bo’i v’shalom …” at the end of Lecha Dodi on Friday night, we should turn to the right, and turn back to the right to complete the rotation (clockwise, this time). To demonstrate the association between these actions and activities in the BHM, I will have to provide a fair amount of background and context for readers who may not be familiar with the workings of the BHM. The analysis will focus on two events: the sacrifice of the Korban Pesach and the kohen gadol’s avodah with the par (bull) and sair (goat) on Yom Kippur.

Brief Overview of the Layout of The BHM and the Mizbeach

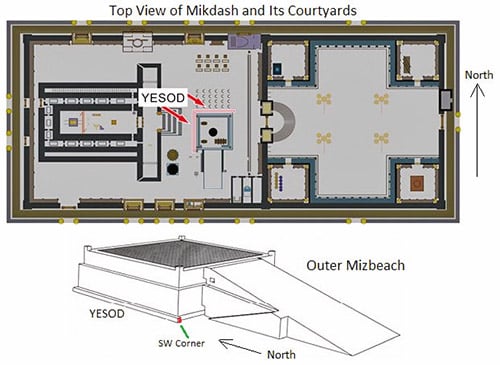

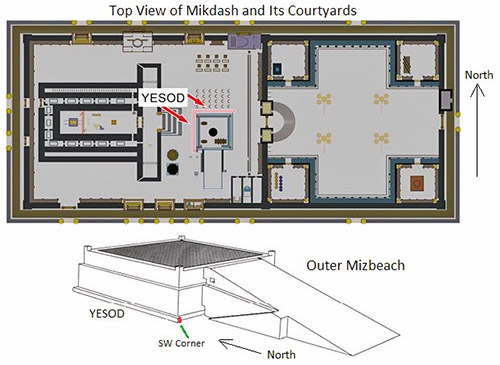

The first diagram below contains a top-level view of the BHM. The large courtyard on the right (the eastern side) is the Ezrat Nashim (men were also allowed there). Fifteen semi-circular steps led up to the Sha’ar Nikanor gate. The entire courtyard area west of the gate is called the Azara. Non-kohanim were permitted into the first 11 amot (an amah is between 1.5 and 2 feet) of the Azara in an area from north to south (135 amot in length) called the Ezrat Yisrael. Beyond that area is the Ezrat Kohanim. The large rectangular object with the partial red border (the color in the diagram is to highlight the yesod; see the next paragraph) is the Mizbeach (32 x 32 amot at the base). The Ezrat Kohanim extends (east-west) 11 amot from the Ezrat Yisrael to the Mizbeach, plus the width of the Mizbeach (43 amot total). The second diagram shows more detail of the Mizbeach.

The Mizbeach comprised three main sections. At the bottom was the yesod (base), 1 amah high and 1 amah wide. Its extent was 32 amot on each of the western and northern sides. It extended just 1 amah into the south side at the southwestern corner (highlighted in the figure in red), and 1 amah into the east side at the northeast corner (not shown in the diagram). I will explain why shortly. Above the yesod was a section that was 5 amot high and 30 x 30 amot in area. The top of that section was a ledge 1 amah wide all around called the sovev (סובב). The uppermost segment was 28 x 28 amot and 3 amot high. On its four corners were “keranot” (קרנות, “horns”), 1 x 1 x 1 amah each. On the south side of the Mizbeach was the kevesh (כבש, ramp), 31 amot long at its base and 16 amot wide.

Yerushalayim lay between the portions of land given to the tribes of Yehuda and Binyamin. This was because of Yehuda’s taking responsibility for Binyamin (Bereishit 43:9 and 44:32), and what that symbolizes for the Jewish people (כל ישראל ערבים זה לזה). In Yaakov’s blessing for Binyamin (Bereishit 49:7), בבקר יאכל עד is interpreted by Chazal to refer to the daily consumption of the korbanot on the Mizbeach that would mostly be in Binyamin’s territory. As we shall see, the application of blood on the Mizbeach was generally above the yesod. Since the southeastern corner of the Mizbeach was in Yehuda’s territory, the yesod could not be built there. A number of korbanot (olah, shelamim, asham) required sprinkling of blood on each of two corners that would ooze to the adjacent sides and thus go “על המזבח סביב” (see multiple verses in Vayikra Chapters 1, 3 and 7). This could only be done in the NE and SW corners, and so the yesod had to extend 1 amah at each of those corners.

Korban Pesach in the BHM

The Mishnah in Pesachim 64a describes the scene on 14 Nissan in the BHM. Thousands of Jews assembled with their small lambs (< 1 year old) on the Temple Mount. They were divided into three kitot (groups), based on the three collective words used in Shemot 12:6 (ושחטו אותו כל קהל עדת ישראל). Since each of those words connotes 10 people in various places in Tanach, each group must have at least 30 people in it. In practice, each group had thousands in it. The men in a group were admitted into the Azara with their lambs, where they or a kohen may slaughter it. That is the first of four “avodot” that all animal korbanot require. The other three may only be done by a kohen: collection of the blood from the shechita into a receptacle (קבלת הדם); carrying the receptacle to the Mizbeach (הולכת הדם); and sprinkling or pouring the blood (depending on the korban), usually on the side of the Mizbeach (זריקת או שפיכת הדם). In order to accommodate the large number of korbanot on Erev Pesach and to provide a spectacle of “ברוב עם הדרת מלך”, the kohanim formed “fire brigade” lines from the shechita sites to the Mizbeach. The first in a line would collect the shechita blood in his receptacle and pass it to the next kohen, and he would pass it on, and so on until the last kohen would apply it to the Mizbeach. He would then pass the empty receptacle back up the line until it reached the first kohen, who would repeat the process with the next animal.

We need to examine this process more closely. The Mishnah says that each kohen in a line first accepted the full container, and then returned the empty one (“ומקבל את המלא ומחזיר את הריקן”). The Gemara (64b) comments that reversing the order was not done. Why? Resh Lakish says because “אין מעבירין על המצוות”—we don’t pass up (ignore the pun) a mitzvah that is presented to us. The source for that rule is in Yoma 33a, from the verse “ושמרמם את המצות” (Shemot 12:17), where the word “matzot” is read “mitzvot.” Rashi says do not delay a mitzvah so that it becomes “chametz” and old.

Consider the procedure in more detail by thinking of the kohanim on the line in adjacent pairs. Let us label them (a, b), (c, d) … where kohen “a” is closest to the shechita end and the later letters are closer to the Mizbeach. A rule you must know is that all avodah must be done with the right hand. In fact, a left-handed kohen may not serve in the BHM. The passing of the receptacles with blood accomplishes הולכת הדם and so must done right-handed. Say kohen c has a container of blood in his right hand. He must pass it to the right hand of kohen d. The passing back of the empty receptacle is not an avodah, and so may be done left-handed. Kohen d passes the empty container in his left hand to c’s left hand after receiving the blood in his right hand (and thus the mitzvah is prioritized, as per Resh Lakish). Kohen c now has nothing in his right hand and an empty container in his left. Kohen d now has a full container in his right hand and nothing in his left. The same state exists between a and b. Now kohanim b and c interact the same way c and d did, as do d and his following kohen e. The result of all this is that the full containers are advancing toward the Mizbeach, and the empty ones are moving back toward the shechita area. This procedure will be applied to our first shul case of two sifrei Torah, but before we do that, we must examine part of the Avodah on Yom Kippur.

Avodah with the Bull and Goat on Yom Kippur

On Yom Kippur, after the kohen gadol (KG) shechted his par (bull), he collected the blood in a receptacle and handed it to a kohen to stir so that the blood wouldn’t congeal (Mishnah Yoma 43b). He then selected via lottery one of the two identical goats brought by the nation for a korban chatat. Following his bringing the ketoret into the Kodesh HaKodashim (KHK), he retrieved the container with the bull’s blood and entered the KHK with it and applied it with a flicking motion in front of the Aron, once upward and seven times downward. He then left the KHK into the Heichal (the room with the Menorah, Shulchan and Golden Mizbeach). The blood receptacles had rounded bottoms to prevent them from being put on the floor (they would tip over if that happened) so that, with all the activity in the BHM, one wasn’t overlooked and not be usable because its blood would congeal. A stand (כן, kein) was in the Heichal on which he placed the container with the bull’s blood. He then left the Heichal to shecht the goat and brought its blood into the KHK and applied it as he did with the bull. At this point he has to put down the goat’s blood, fetch the bull’s blood, and apply it to the Parochet (curtain) separating the KHK and the Heichal.

There is a debate between Rabbi Yehuda and the Chachamim (Mishnah Yoma 53b) as to how many keinim (stands) were in the Heichal. According to R. Yehuda there was only one, and so the KG, who held the receptacle with goat’s blood in his right hand, perforce had to remove the container with the bull’s blood with his left hand and place the one with the goat’s blood in its place. After flicking the bull’s blood toward the Parochet (again, once upward and seven times downward), he would repeat the procedure with the container of goat’s blood. The reason R. Yehuda thinks that there weren’t two keinim was because he believes that the KG could err and confuse which container was which if both were on keinim. The Chachamim feel that there were enough discriminants between the two containers (color of the blood and other factors) that one kein sufficed. Rava in Yoma 56b rules according to the Chachamim and says that the specific order followed by the KG when he had to get the bull’s blood and was holding the goat’s blood was הניח דם השעיר ונטל דם הפר—he first put down the container with the goat’s blood on its kein and then took the bull’s blood from its kein with his now-free right hand. That way, both the placement on, and removal from, a kein were done with his right hand.

Choreography With Two Sifrei Torah

Rama rules in Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim 147:8 (Laws of Kriat haTorah) that after reading the first of two Sifrei Torah, the first is not removed from the Shulchan until the second one is placed down next to it שלא יסיחו דעתן מן המצוות—so that there should not be a moment with no Torah on the table (literally, so that they should not lose awareness of the mitzvot). Magen Avraham (note 11) compares this to the KG according to Rava first placing down the goat’s blood on its kein before removing the bull’s blood from its kein, all with his right hand. Therefore, the first Torah should be removed from the right side of the table, and hence should be slid right to accommodate the second Torah. He then quotes Hagahot Maimoniyot, who cites Rosh in the name of Rabbeinu Yona in the second perek of Masechet Shabbat that a proof to Rama comes from the way the blood containers were passed from one kohen to another on Erev Pesach. Each kohen first took a full container before returning an empty one. So too, it seems, we take the second Sefer Torah before returning the used one (which is analogous to the empty blood receptacle). Magen Avraham thinks there is no support for Rama from that Gemara. Rama claimed the reason was that there should be no moment in the transfer when the shulchan has no Torah on it. But Resh Lakish said the reason for accepting the container with blood first was because of “אין מעבירין על המצוות” and not so that the kohen should not be bereft of the mitzvah of הולכת הדם by being empty-handed. Moreover, going back to our close examination of the transfers by the “fire brigade,” if kohen d accepts the container with blood from c first before handing him his empty container, then kohen c was empty-handed after giving his container to d and before receiving the empty one from d. Clearly, the Rama’s reason does not apply. The conclusion therefore is that the reason to scoot the first Sefer to the right and place the second down on its left before removing the first one is to mimic what was done in the BHM during the Yom Kippur and Pesach avodot explained above.

Turn, Turn, Turn

The Korban Chatat of an individual or on a holiday was the only one whose blood was applied to each of the four keranot atop the Mizbeach. To do this, the kohen ascended the kevesh on the south side up to the sovev. He then turned right and walked on the sovev to the SE corner and applied blood to that keren. He continued around counter-clockwise and applied blood consecutively to the NE, NW and SW corners. See the Mishnah in Zevachim 5:3. Why did he follow that order? The Gemara (Yoma 58b) cites Chronicles II 4:4, which describes the water tank built by Shlomo Hamelech for the BHM (Yam shel Shlomo). It was made of cast copper and was supported by 12 cast copper “oxen” arranged in a square, three per side facing outward. See the figure (only six oxen are shown). The pasuk describes the positions of the oxen as “three facing north, three facing west, and three facing south and three facing east.” This counter-clockwise description is the basis for the kohen’s walk around the

Mizbeach on the sovev. The Gemara generalizes the directional description by saying that “all turns that one turns should only be to the right.” The kohen began his circuit by turning right at the top of the kevesh onto the sovev.

Let us return to the Heichal on Yom Kippur after the KG finished applying the bloods of both the bull and the goat to the Parochet. He then mixed the bloods together (the details are not important now, but think of the wines after bentching at sheva brachot) and had to apply the mixture to each of the four corners of the small Golden Mizbeach (used all year for burning ketoret) in the middle of the Heichal (and afterward sprinkle the blood seven times on the surface of that Mizbeach). Its square cross-section was only 1 amah by 1amah, so the KG could reach all four corners without moving. In what order did he apply the blood to the four corners?

The Mishnah in Yoma 51b cites a debate as to whether there were two overlapping curtains between the KHK and the Heichal with an amah separating them (the Chachamim’s opinion) or one curtain (Rabbi Yosi’s opinion). According to the Chachamim, the outer curtain (both curtains extended from north to south) was pinned back with a clasp at its south end, and the inner one was pinned back at its north end. The KHG would enter the KHK by going inside the outer curtain on the south side of the Heichal, proceed between the two curtains moving north, and then enter the KHK through the opening at the north end of the inner curtain. He would then move south along the inner curtain until he got to the area between the Aron’s poles. According to R. Yosi, the single curtain was pinned back at its north end, and the KHG would enter the KHK there, similar to the Chachamim. The critical difference occurs when he emerges from the KHK. According to the Chachamim, he emerges on the south side of the Heichal, and according to R. Yosi, on the north side. He then must move directly to the Golden Mizbeach. Let us label the four corners of that altar, starting at the northeast corner and moving counter-clockwise, as NE, NW, SW, SE. Rabbi Akiva agrees with the Chachamim in Yoma 58b and says the KHG arrives at SW first; R. Yossi haGalili agrees with R. Yosi and says he arrives at NW first. They both agree that the KHG cannot apply blood to the first corner he comes to because the pasuk (Vayikra 16:18) says “ויצא אל המזבח אשר לפני ה’ וכפר עליו מדם הפר ומדם השעיר ונתן על קרנות המזבח סביב.” The word “v’yatzah” is taken to mean he goes to the outer (eastern) end of the altar. He is not violating Resh Lakish’s edict of not passing over a mitzvah opportunity by doing so, since the Torah prescribes it. According to Rabbi Akiva, moving east from SW, the KHG arrives at SE, and according to R. Yossi haGalili he passes NW and begins NE. R. Yossi haGalili says that the direction of application should be counter-clockwise as with the chatat. R. Akiva says that since one corner was skipped over, that corner should be returned to second, even though it means moving clockwise. So according to R. Akiva, the order of application is SE, SW, NW, NE. According to R. Yossi haGalili, it is NE, NW, SW, SE. The takeaway is that in principle, turning should be to the right.

As mentioned above, the blood of an asham or shelamim or olah was sprinkled (זריקה) at the NE and SW corners of the outer altar. The verse in Devarim 12:27 states “ודם זבחיך ישפך על מזבח ה’ אלקיך”. Rashbam in Pesachim 121a cites Zevachim 37a that the action of pouring the blood cannot apply to korbanot for which the Torah specified sprinkling, and therefore it must apply to the first-born male animal sacrifice (Bechor Beheimah), the Maaser Beheimah sacrifice and the Korban Pesach. Only one pouring application is required for each, anywhere above the yesod (Zevachim 5:8). Me’iri (Beit haBechirah Pesachim 64a) says that in practice, the blood of the Pesach was poured at the NE corner of the Mizbeach. Why? Because he seems to think that the kohen poured the blood down from the sovev, and since he always turns right when ascending the kevesh and reaching the sovev, the first place he comes to that has the yesod underneath is the NE corner. He must then pour the blood there because of Resh Lakish’s rule.

The conclusion is that we mimic the turning to the right in the BHM in our shul services by having anyone who goes up to the aron move to his right and proceed counter-clockwise to get the Torah and to return it to the shulchan. Similarly, when we turn around for Bo’i v’shalom on Friday night we should turn to the right and again to the right to return to our original position. These actions have no mystical significance but rather are a constant reminder that a shul is a Mikdash Me’at (Yechezkel 11:16) and serves as a vestige of what occurred in the BHM, and will occur again במהרה בימינו.

Postscript: The Mishnah in Zevachim (6:2-3) points out that the עולת העוף was normally brought at the SE corner on the sovev, and to get there, the kohen would turn right from the top of the kevesh. But when there was a lot of activity at that corner he could offer it at the SW corner because it also wasn’t far from the pile of ashes to the east of the kevesh. Since walking around the whole Mizbeach might cause the bird to die because of the smoke, he walked directly to the left. The same for the ניסוך המים ויין. Since there are no smoke issues in a shul, the rule of turn to the right always applies.

Richard Schiffmiller is a musmach of YU and has a Ph.D. in physics. He is retired after 40 years in the electronic warfare industry. He holds eight patents, mostly for passive geolocation of radars.