Last month, a group of students had the opportunity to visit a new exhibit at the Yeshiva University Museum on the life and legacy of the Rambam, one of the most influential Jewish thinkers in modern history. Between his written works of Halacha and hashkafa, as well as his career in medicine and communal leadership, the rabbi also known as Maimonides has definitely earned his standing as the greatest Moshe since Moshe Rabbeinu. During our tour of the exhibit officially entitled “The Golden Path: Maimonides Across Eight Centuries,” we viewed some of the Rambam’s manuscripts, letters, old and new printings of his books, artifacts from his communities, and future works that have utilized his ideas. The exhibit consists of three rooms, each with a different focus: the manuscripts from the Rambam himself, the manuscripts and later printings of his works from the medieval times and the effects of the Rambam on modern times.

While exploring the first room which highlights the Rambam’s early manuscripts, we learned that except for his magnum opus Mishneh Torah, the Rambam published in Judeo-Arabic, meaning he wrote with Hebrew characters and Arabic vocabulary. While not as prevalent in our times, this practice was used by other Jewish communities, such as the Persians’ use of Judeo-Persian. One aspect of the exhibit that made the Rambam seem more personable was the display of unfinished drafts of his works. Part of the beauty of witnessing these early revisions is the ability to understand how the Rambam’s works were living documents, constantly under revision for incremental improvements. It is often easy to picture the Rambam’s work as perfected on the first go, but viewing the documents in this context helped provide a human element to the writings that was previously unilluminated.

As time progressed and reproductions were made of the Rambam’s books, several developments were noticeable at the exhibit that demonstrate the Rambam’s popularity in the immediate time after his death. The Rambam’s popularity is shown through reproduction of his work by hand and print in early centuries, despite containing some radical perspectives for his time. For instance, he wrote that one only needs to learn the Torah She’bichtav and Mishneh Torah, as his book consolidated Torah She’baalpeh.

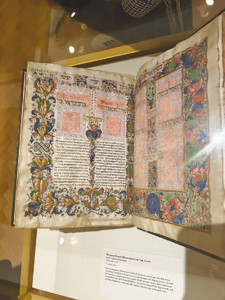

Though during the 15th century primarily Machzorim and Haggadot were treated with ornate design, his Mishneh Torah is decorated with precious materials and spectacular artistry as seen in this picture. Further, we were able to learn about the history of liturgy throughout the exhibit, witnessing the shifts as books transitioned from written form to early printed works to illuminated manuscripts. Through the examination of this progression, we learned a lot about the history of the printing process and books in general.

Transitioning to modern times, the third room showed several ways in which the Rambam’s presence is felt even several generations after his passing.

One fascinating emergence of the Rambam’s impact is in a prayer composed after the American Revolution. The prayer incorporates the Rambam’s 13 Principles of Faith in entreating Hashem to protect the 13 recently established colonies, even mentioning General George Washington and Governor George Clinton of New York by name. The prayer also asks for peace, prosperity, the safety of freedom and the ushering in of the final coming of Mashiach.

Around this area of the exhibit was a manuscript from Issac Newton who used the Rambam’s writings in his astronomical insights. Many scientists and astronomers from that era looked at the Rambam’s works for inspiration and knowledge. This manuscript from Issac Newton is a textbook example of that. Newton, who read and understood Hebrew, used the Rambam’s explanation of the Beit Hamikdash and its rituals in hopes of learning the structure of the earth. Newton believed that the structure of the Beit Hamikdash reflected the structure of the universe. This also demonstrated that Newton looked at the Rambam’s astronomical writings about the moon’s cycle to calculate, reform and establish the Julian calendar in England.

The exhibit is located at the YU Museum in the Center for Jewish History in New York City until December 31. If we had to pick one line to impart after visiting the exhibit, it would be one of Rambam’s quotations from his introduction to Pirkei Avot that was on one of the walls of the exhibit: “V’shma haEmet mimi sheamru, hear truth from whatever source it comes.”