In Sanhedrin 33a, a third-generation Amora, Rav Sheshet (citing Rav Assi, Rabbi Assi or in Sanhedrin 6, Rabbi Ami) distinguishes between two types of error in judgement, namely טְעָה בִּדְבַר מִשְׁנָה, erring in an explicit mishnaic/taught source, and טָעָה בְּשִׁיקּוּל הַדַּעַת, erring in deliberation. In the first type of error, the decision is revoked (so any money would be returned by one litigant to the other), while in the latter, the decision stands (so the judge is responsible for the lost money from his personal funds).

We might point to Eruvin 67a—when (Suran Amora) Rav Chisda and Rav Sheshet met, Rav Chisda’s lips would tremble at the thought of his colleague/disputant’s mastery of Tannaitic statements, while Rav Sheshet’s entire body would shake from Rav Chisda’s masterful analysis. In an incident in Nehardea—related in Bava Metzia 38b, Rav Sheshet resolved a matter from a baraita and Rav Safra suggested that the baraita “perhaps” taught something else, Rav Sheshet mockingly replied, “Perhaps you are from Pumbedita, where people pass an elephant through the eye of a needle (with their pilpulic analysis),” then proffered his own reasoned response. If so, it makes sense for Rav Sheshet to relay this statement giving primacy to knowledge of teachings over analysis, as a basic prerequisite to valid judgement.

Extent of Dvar Mishna

Back in our sugya, Ravina II asks his teacher—sixth-generation Rav Ashi—about the extent of טְעָה בִּדְבַר מִשְׁנָה. Rav Ashi applies this to not knowing a statement of transitional Tannaim/Amoraim, Rabbi Chiyya and Rabbi Oshaya. As Rashi explains, these Sages assembled Tannaitic works of baraita/Tosefta. He further applies it to positions of Rav and Shmuel, first-generation Amoraim. Rashi explains that these are positions they arrived at through reason, rather than recounting Tannaitic traditions. I wonder, though, if their status is not as Amoraim but as founders of Sura/Nehardea holding established positions, from which other Amoraic discussions begin. Perhaps their statements have a “mishna” status as well.

Finally, when asked about the status of Ravina II and Rav Ashi’s own positions, Rav Ashi says, “Are we reed cutters in the pond?” Rashi explains that טְעָה בִּדְבַר מִשְׁנָה even applies to one erring in the words of later Amoraim. I, again, wonder whether Ravina and Rav Ashi are mere examples of later Amoraim, but Ameimar or Rav Pappa are equivalent; or whether Ravina and Rav Ashi have special status as redactors of the Babylonian Talmud, creating a standardized oral Talmudic corpus which others should know.

Erring in Deliberation

Chronologically but not textually before Ravina and Rav Ashi discussed this, fifth-generation Rav Pappa weighed in to define טָעָה בְּשִׁיקּוּל הַדַּעַת. Rav Pappa is primarily the student of Rava, who in turn taught/presided over Pumbedita academy, but who studied from several Amoraim like Rav Nachman (Nehardea), Rav Chisda (Sura) and—to a lesser extent—Rav Yosef (Pumbedita). Rav Pappa is also the teacher of Rav Ashi, who is no mere reed-cutter!

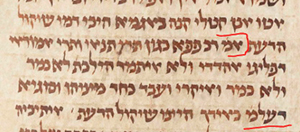

Rav Pappa said: כְּגוֹן תְּרֵי תַּנָּאֵי אוֹ תְּרֵי אָמוֹרָאֵי דִּפְלִיגִי אַהֲדָדֵי, וְלָא אִיתְּמַר הִלְכְתָא לָא כְּמָר וְלָא כְּמָר, וְאִיקְּרִי וַעֲבַד כְּחַד מִינַּיְיהוּ, וְסוּגְיָא דִּשְׁמַעְתָּא אָזְלִי כְּאִידַּךְ—הַיְינוּ שִׁיקּוּל הַדַּעַת—“Such as two ‘Tannaim’ or two ‘Amoraim’ who argue with one another, and the halacha is not stated like this one or that one, and it occurred that he ruled like one of them, and the sugya of the shmayta/contained discussion goes according to the other one—that is (erring in) deliberation.”

Translating and making sense of the above text from the printed Talmud is difficult. Rashi’s dibbur hamatchil and several manuscripts—such as Florence 8-9—replace וְסוּגְיָא דִּשְׁמַעְתָּא with וְסוּגְיָא דְּעָלְמָא, which I prefer. Rashi explains that most of the judges (in the world) prefer the words of the second Sage. I still find this explanation difficult. How does סוּגְיָא translate to “judges?” Also, is there really no judicial independence? If there’s dispute between Sages and no definitive ruling, is it truly such an error for a judge to be a “daat yachid—to go against the majority of his colleagues if polled”—to think that Rav Yosef’s position and interpretation of sources is more convincing than that of Rabba? Is that truly an error, such that the judge must make the losing litigant financially whole?

Competing Oral Girsaot

My alternative explanation follows: The word “Tanna” means either a Sage of the Tannaitic era, up to Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s generation, or else an Amoraic Sage whose role was to recite Tannaitic teachings. Alternatively, the word “Amora” means either a Sage of the Amoraic era, or an Amoraic Sage whose role was to recite an Amoraic Sage’s teachings. Aside from that formal role, a “Tanna” or “Amora” could be a Sage of the same general era who related/interpreted a named Sage’s teachings.

For example, in Bava Metzia 58b, תָּנֵי תַּנָּא קַמֵּיהּ דְּרַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק—a reciter of Tannaitic teachings taught a baraita before fifth-generation Amora Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, who replied to him. In Zevachim 94b, after Rava discovered he erred in a public discourse, he appoints an אָמוֹרָא upon it to promulgate it to the public. Regarding conflicting Tannaitic statements, in Brachot 3a, a baraita and Tosefta are contradictory regarding the fifth-generation Tanna Rabbi Meir’s opinion, and the Talmudic narrator suggests this is תְּרֵי תַּנָּאֵי אַלִּיבָּא דְּרַבִּי מֵאִיר, either two of Rabbi Meir’s students, or two Amoraic reciters, with variant traditions in Rabbi Meir.

Similarly, in Shabbat 112b, given contradictory positions attributed to Rabbi Yochanan, the Talmudic narrator suggests they are אָמוֹרָאֵי נִינְהוּ וְאַלִּיבָּא דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, two Amoraim (whatever that means) each with a variant version of Rabbi Yochanan. We often encounter such variants: Ravin, or Rav Dimi, comes from the land of Israel with a version of Rabbi Yochanan’s position. Or, in Ketubot 7b, Rav Pappi and Rav Pappa say different statements מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרָבָא, their teacher.

Sometimes the Gemara itself—initially orally transmitted and subsequently, textually transmitted—has variant traditions of what Sages said, and, indeed, the entire conversation. The words signifying this are אִיכָּא דְאָמְרִי, or וְאָמְרִי לַהּ for shorter textual variants. Which variant wins?

Weighing Variants

That’s how I interpret Rav Pappa’s בְּשִׁיקּוּל הַדַּעַת. Given girsological variants, each version is “mishna,” so he doesn’t err in not knowing it. However, he should how these words are understood in other Sages’ discussions, or in other sugyot throughout the Talmud (סוּגְיָא דְּעָלְמָא). If one reading prevails, he should grant greater weight to that version/opinion.

Consider Bava Batra 2b: One variant concludes that hezek reiyah, damage by sight, is not a halachically valid concern for one partner to compel the other. The second variant reaches the opposite conclusion. Both variants involve interpreting/reinterpreting Tannaitic and Amoraic statements. The Rosh notes that Rif only quotes the second variant, and champions that version because of (a) its relative internal strength, existence of named Amoraim discussing it, and (b) what’s important for us, (c) that sugyot throughout the Talmud assume that “hezek reiyah” is a valid concern. Similarly, in Tosafot to Avodah Zara 7a, in discussing lishna kamma versus lishna batra (first and second internal Talmudic variants), Rabbeinu Shimshon says that if other sugyot—throughout the Talmud—accord with one reading, we follow that reading. This sounds like Rav Pappa!

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.