Ben Zakkai appears in Sanhedrin 40a, but I don’t know who he is. The Mishna states that whoever increases in bedikot—examinations of witnesses about tangential details of the event—is praised. Indeed, in one incident, Ben Zakkai asked about the stems of figs where the event—such as a murder—

took place.

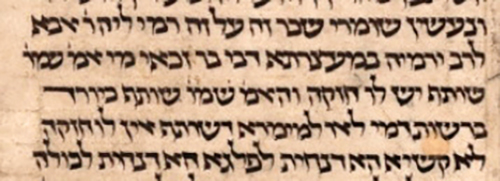

Is Ben Zakkai the famous Tanna and Nasi, Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai? The Talmudic Narrator entertains that notion in Sanhedrin 41a, then notes a problem, drawing on baraitot and Amoraic statements found elsewhere in Shas. A baraita taught that Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai lived for 120 years. For 40 years, he dealt in business (prakmatya); for another 40, he studied; and for another 40, he taught. Another baraita states that 40 years before the Second Temple’s destruction, the Sanhedrin was exiled from the Chamber of Hewn Stone. When considering the import of this statement, Rabbi Yitzchak bar Avdimi—a first generation Amora of the land of Israel—explained: they stopped adjudicating fines. The Talmudic narrator expresses astonishment that they wouldn’t deal with fines, and revises this to mean that they wouldn’t judge capital cases.

Now, the interrogation regarding fig stems was about a capital case, as is clear from analysis by Rami bar Chama and Rav Yosef. Since Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai was only prominent for 40 years at the end of his life, after the churban, and 40 years before the churban they stopped judging such cases, how could he have grilled this witness? The Talmudic narrator briefly suggests this wasn’t Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai. Indeed, logically, why would the mishna omit his honorific? However, since a baraita records a variant in which it’s explicitly Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai with the honorific, the narrator retracts. Rather, he’s called this because—at the time of his 40 years of study—he was a student sitting before his teacher when he made this suggestion of how to interrogate. His title is therefore accurate for the time he took this action. It’s noteworthy that, if the narrator’s identification is sound, the Amoraim followed the mishna’s lead in using the less respectful term. Thus, Rav Yosef surprisingly said that “Ben Zakkai” is different, for he equated examinations (of tangential matters) with interrogations (of central matters).

We must note Rosh Hashanah 31b, where the same 120/40 calculation is brought to bear by the Talmudic narrator. Fifth-generation Amoraim, Rav Pappa and Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, argue about the ninth and final ordinance by Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai. Rav Pappa said it concerned the fruit of the fourth-year grapevine (kerem revai), which was typically brought to Yerushalayim instead of redeemed, so as to adorn the city. He decreed that—after the Temple’s destruction—this was no longer necessary.

Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak said it regarded the strip of crimson wool, tied outside at the opening of the entrance to the Temple (Ulam) for Yom Kippur. Crimson turning white signified atonement of their sins, and the people would rejoice. They were saddened when it stayed crimson. They instituted to tie it on the inside where few could see it, but when people then peeked, his decree was to instead tie half to the scapegoat and half to a nearby rock. This was in the forty years leading up to the Temple’s destruction, when the crimson never turned white, so people would be regularly saddened and distressed.

The Talmudic narrator supplies an explanation, why each Amora doesn’t take the other’s position, and what the first Amora would have responded to. Rav Pappa would have pointed out the 120/40 calculation; the crimson was before the Temple’s destruction, while Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai only rose to prominence afterwards. Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak would say that he merely suggested it, and his teachers instituted it in his name.

Other Occurrences

The name “Ben Zakkai” occurs elsewhere. In Shabbat 34a, fifth-generation Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai wanted to know whether a certain marketplace had a presumption of ritual purity, so that he might permit Kohanim to enter. A certain elder told him, “Here, Ben Zakkai cut the terumah of lupines.” Nothing definitively establishes who this “Ben Zakkai” is, but the implication is that this is someone prominent who Rabbi Shimon should know; since an elder testified to this, it should be someone a few scholastic generations back. Also, Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai was a Kohen, which fits with the terumah and purity concern.

In Chullin 52a, Ulla quotes Ben Zakkai that, if the majority of an animal’s ribs, even if on just one side (six ribs) were dislocated, that’s sufficient to render the animal a treifa. Only if the ribs are broken are a majority of both sides needed. However, Rabbi Yochanan—presumably the famous first- and second-generation Amora—disagrees. The implication is that this Ben Zakkai is an Amora—not an early Tanna. However, take note that while the Vilna text has “amar Ulla ben Zakkai amar,” indicating a quote, and this is matched by some manuscripts (Hamburg 165, Munich 95, Vatican 120-121, Vatican 122, and Vatican 123), the Soncino and Venice printings skip the first “amar,” making it an unknown Amora, Ulla ben Zakkai. Rabbeinu Gershom also seems to have one person talking, Ulla bar Zakkai.

Also, Rashi ad loc has the girsa of “Bar Zakkai,” and comments, “I don’t know who he is.” Rav Yaakov Emden weighs in on Rashi’s uncertainty, saying that if this were the “Ben Zakkai” of our sugya in Sanhedrin, Rabbi Yochanan (the Amora) would not argue upon him. I’d note the existence of a fifth-generation Tanna, Rabbi Yochanan I, who might have argued. Even so, “Bar Zakkai” isn’t the same name as “Ben Zakkai.”

Branching out to Bar Zakkai, in Bava Batra 42b, Rabbi Abba raised a contradiction to Rav Yehuda in the cave of Rav Zakkai. Now, the printed מערתא—burial cave is in error and manuscripts have the less common מַעֲצַרְתָּא, either a pressing room, a meeting room, or a school house. Further, רב is בר reversed, and manuscripts are split as to which it is. Florence 8-9, Oxford 369, Paris 1337 and Vatican 115b have “Bar.”

Alternatives

I dislike using calendrical calculations to discover peshat, in either Tanach or Gemara. There are often so many moving parts—assumptions turned into temporal constraints—which if relaxed might allow for alternative explanations.

For instance, 40 may be a magic number. In terms of judges (shofetim,) Otniel and Eli ruled for 40 years; for Devorah, the land had peace for 40 years. It rained in the mabul for 40 days and nights, and Moshe was on Har Sinai for the same period. The Israelites were in the wilderness for 40 years, and so on. Similarly, 120 years is completeness. Moshe Rabbeinu, Hillel Hazaken (a previous Nasi) and Rabbi Akiva all lived to 120. It is also surprising that he managed to split his life into precise sets of 40 years. Regarding a suggestion (Kiddushin 30a) that one split one’s life learning into three parts—Scriptures, Mishna and Talmud—the Gemara wonders who knows up front their span of years. Apparently, Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai did! Alternatively, some of this is poetic or approximate, or we can question the remapping of “fines” to “death penalty,”—either way, allowing an empowered Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai to grill witnesses in capital cases.

I don’t generally favor the idea of Sages assigned names based on their statements, but I am a big fan of puns. Assuming we can argue with the one baraita that out the name as “Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai,” let us notice that Zakkai means to declare innocent or acquit. This word is often used in this very context, for instance immediately above in the Mishna with the statement שְׁנֵים עָשָׂר מְזַכִּין וְאַחַד עָשָׂר מְחַיְּיבִין—זַכַּאי, if 12 vote to acquit and 11 find him liable, he’s acquitted. By grilling the witnesses about many minor tangential details, where conflicting testimony (see Rav Yosef) will invalidate them, Ben Zakkai’s actions would likely lead to acquittal.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.