Let us say your father and rebbe are both carrying heavy boxes and need assistance putting it down. A mishna in Bava Metzia 33a says your teacher takes precedence, unless your father is also a Torah scholar. The same for returning his lost item. A baraita there (also Tosefta Bava Metzia 2:13) presents a Tannaitic dispute in defining this teacher. Rabbi Meir—a fifth-generation Tanna—maintains it’s the teacher who taught him חׇכְמָה/wisdom1 rather than the one who taught him Scripture and mishna. His colleague Rabbi Yehuda says this is the one from whom he learned most his חׇכְמָה/wisdom2. His colleague Rabbi Yossi says that this teacher is even one who enlightened his eyes in understanding a single mishna.

Rava—a fourth-generation Babylonian Amora—gives an example of Rabbi Yossi’s singular teacher: “Such as Rav Sechora, who explained zuhama listeron,” which is a utensil with a fork on one end and spoon on the other—mentioned in the mishna in Keilim 13:2. There, even if its spoon was taken, it still is susceptible to tumah on account of its fork and vice versa. They use the utensil to remove the zuhama/froth or foul matter from the pot.

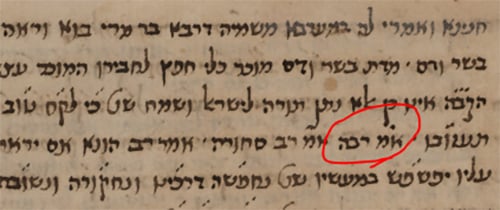

The problem with this is our sugya in Sanhedrin 49b. The mishna had stated there were four court-imposed death penalties, and enumerated them. Rava cited Rav Sechora who cited Rav Huna that wherever the Sages taught by means of an enumerated list, the meaning isn’t significant—except by the seven abrasive substances—where the meaning is significant. In Sanhedrin, Sechora is uniquely spelled with an aleph, so it is hand to find, but spelled with a final heh, we find אָמַר רָבָא אָמַר רַב סְחוֹרָה אָמַר רַב הוּנָא scattered across Shas. If Rav Sechora provides Rava with a corpus of Rav Huna statements, how could Rava claim to have such limited dependence upon Rav Sechora, only defining one mishnaic term?

Other evidence that Rava held high regard for Rav Sechora is Nedarim 22b. Rava praised Rav Sechora as a great man to Rav Nachman. Rav Nachman said, “When Rav Sechora comes to you, send him to me.” Rav Sechora had a vow to dissolve. Rav Nachman proposed various approaches to open/undermine the vow. “Did you have this thought in mind when you vowed?” Each time, Rav Sechora answered in the negative. Eventually, Rav Nachman became upset and dismissed him. Then, Rav Sechora undermined his own vow, saying, “Had I known Rav Nachman would have become so upset, I would never have vowed.”

Rav Sechora’s Statements

Let’s review Rav Sechora’s quotations of Rav Huna: In Brachot 5a, grappling with theodicy, Rava or third-generation Rav Chisda—associated with Sura academy—says one who suffers should examine his actions, because suffering typically comes from transgressions. Rava quoting Rav Safra quoting Rav Huna—associated with Sura—discussing yisurin shel ahava, interprets a verse in Yeshaya 53 to describe suffering imposed on those righteous in whom Hashem delights.

In Brachot 26a, the mishna had stated that one must distance himself four cubits from urine or faeces in order to recite Shema. Rava → Rav Sechora → Rav Huna says this is only if it’s behind him. Before him, for Shema and Shemoneh Esrei, it must be distanced as far as the eye can see.

In Shabbat 24a, Amoraim grapples with the question of mentioning Chanukah in bentching. Rava → Rav Sechora → Rav Huna says one does not. In an incident in Rava’s house, someone thought to mention it in Bonei Yerushalayim. Rav Sheshet says to mention it.

In Eruvin 54b, he interprets a verse in Mishlei, which says that if a person turns his learning into bundles (chavilot—from hevel with a heh—by learning a lot at a time) will diminish his learning, but one who learns little by little will retain and increase. The same citation chain and quote appears in Avodah Zara 19a, embedded in a group of interpretations of verses from Mishlei. In Yevamot 106a, the quote is that judges may officiate at a chalitzah ceremony despite not recognizing the yavam and yevama, with various downstream halachic repercussions. Meanwhile, Rava himself disagrees, that the judges may not officiate.

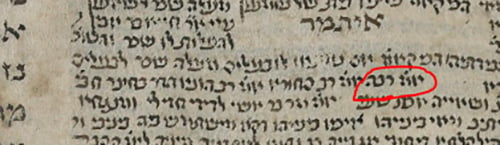

In Bava Kamma 21a3, in a case of “zeh neheneh vezeh lo chaser—one who squats in another’s courtyard without his knowledge need not pay him money,” and according to Munich 95, this chain of Amoraim interprets a verse in Yeshaya that an unoccupied house eventually collapses.

Finally, in Menachot 14b, he says that if one attached tzitzit to three corners of a three-cornered garment, then turned it into a four-cornered garment and attached tzitzit to the fourth corner, it’s not valid because of the principle of תעשה ולא מן העשוי.

Proposed Resolutions

Tosafot discusses this difficulty in several of these sugyot. In Sanhedrin, they suggest (a) that the singular mishnaic elucidation was Rav Sechora’s own insight, while the others were simply channeling Rav Huna. Alternatively, (b) despite having taught Rava much more, Rava’s point was just that had he only taught this one thing, he would be considered his teacher. Alternatively, (c) at this point in time, Rav Sechora had only taught Rava this one thing. In Yevamot and Avoda Zara—besides reason (b)—they suggest (d) that the girsa in Sanhedrin should be Rabba, not Rava, who only learned one thing, whereas Rava was, indeed, his talmid muvhak.

The answer that speaks most to me is (a). Rava happened to only have one mishna elucidation from Rav Sechora speaking for himself4. The rest are just transmitting a corpus of six Rav Huna statements, which Rava transmitted in turn to the Pumbedita academy. Nor do I think that transmitting six statements is enough to transform Rava into his talmid muvhak, in the same way that he would be to Rav Nachman or Rav Chisda.

I’ve edited this article to remove detailed manuscript variants discussions, so briefly: I haven’t seen manuscripts of Bava Metzia (about mishna elucidations) with Tosafot’s proposed Rava/Rabba switch, but it could work. In several of the other sugyot, some manuscripts and printings vary in the citation chain, such as Rabba bar Rav Sechora → Rav Huna, or Rabba → Rav Sechora → Rav Huna, or Rav Chisda → Rav Huna → Rav. We’d have to decide if this is plausible, both in terms of scholastic generation (for Rabba is third-generation, like Rav Sechora) and in which Amoraim react to the statement.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Rashi: Wisdom as the sevarot of the reasons of laws laid out in the mishna; and to understand them so that they are not contradictory; to understand the reasons for prohibition and permission, liability and lack thereof, which is called “Talmud” (not “Gemara” which our censored Rashi texts have).

2 Rashi—despite the same word חׇכְמָה appearing—explains this as the majority of his knowledge, be is in Scripture, Mishna or Talmud (again, not “Gemara”).

3 While the printed version and some manuscripts have אָמַר רַב סְחוֹרָה אָמַר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר רַב, Munich 95 adds “Rabba” at the start of the chain and omits Rav from the end, and we’ll rewrite this as Rava.

4 And Brachot 26 doesn’t count.